Sandwell is made up of six distinct towns – West Bromwich, Wednesbury, Oldbury, Rowley Regis, Smethwick and Tipton – each comprising of its own smaller settlements and distinct localities, the old district councils of West Bromwich and Warley being merged to become one metropolitan authority in the political reorganisation of boundaries in 1974.

When Steve Trow took his Dad (born and bred in West Brom) to see a piece of community theatre in Cradley, about a topic he thought would be of local interest – the famous Women’s Chainmakers Strike of 1910, his Dad’s only comment was “Very interesting, but I ai’ ever bin to Cradley.” Although it was only a matter of 8 miles distance, it may as well have been about an event in Vietnam. The parochial nature of the borough was something that Jubilee tried to grapple with by running ‘area projects’, focusing on the perceptions of places and the attachment of participants and audiences to them.

A celebration of place, identity, heritage if you will. These projects aimed to bring people together and increase their sense of connection to that community; producing common shared stories and representations.

The issue of parochialism is a contemporary concern. When West Bromwich Trades Council and Warley Trades Council agreed to merge in 2013 and finally be known as Sandwell Trades Council, the Chair of the organisation commented, “It’s only taken us 39 years to get used to the idea that we should be called Sandwell and work together.”

Paul Kingsnorth wrote on this subject in the Guardian: ‘Sometimes, the best way of telling new stories is to reclaim old words. The word “parochial” might be a good place to start. “All great civilisations are built on parochialism,” wrote the Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh in 1952. “Parochialism is universal; it deals with the fundamentals.” Parochialism is universal: it sounds like a contradiction, but only if you don’t fully grasp its meaning. “Parochial” literally means “of the parish”. It denotes the small and the particular and the specific. It means knowing where you are. It can also mean insular and narrow-minded, but it doesn’t have to, any more than “cosmopolitan” has to mean snobbish and rootless.

This negative meaning has attached itself to the word because contemporary globalised culture is resolutely anti-parochial. It sets out to destroy local particularity and our attachment to it, because if we remain attached to it we may not buy into the placeless nowhere civilisation that is being built around the globe in the name of money. At its best, a radical parochialism may be the most effective means of resisting this global machine. As Kavanagh implied, without a parochial culture, there can be no culture at all.’

“A community cannot be a community without a shared narrative.”

– Julian Rappaport, ‘Community Narratives: Tales of Terror and Joy’

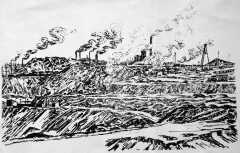

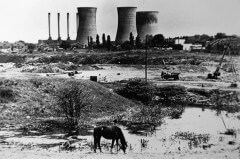

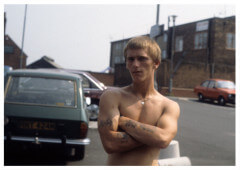

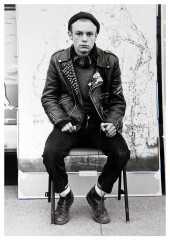

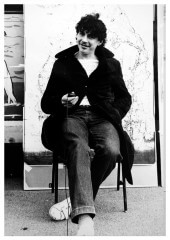

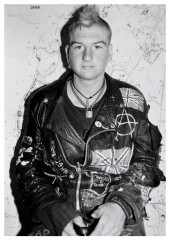

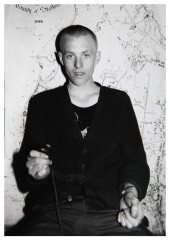

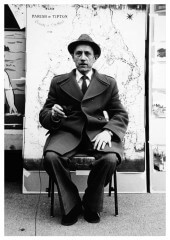

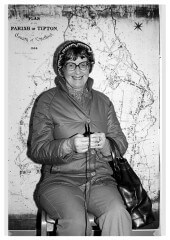

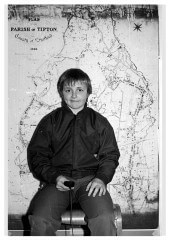

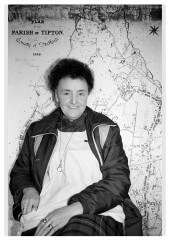

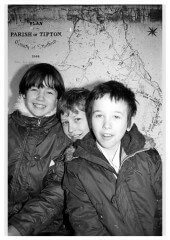

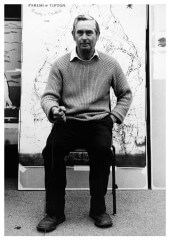

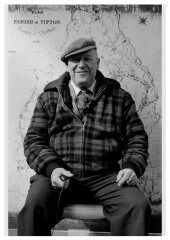

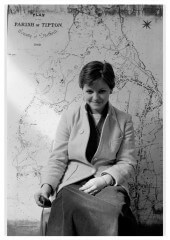

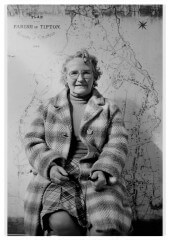

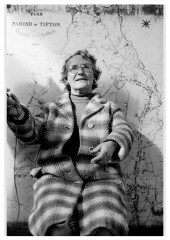

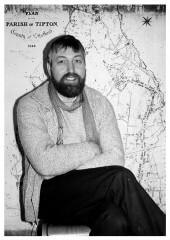

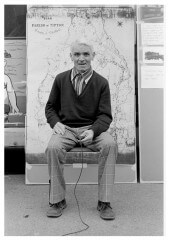

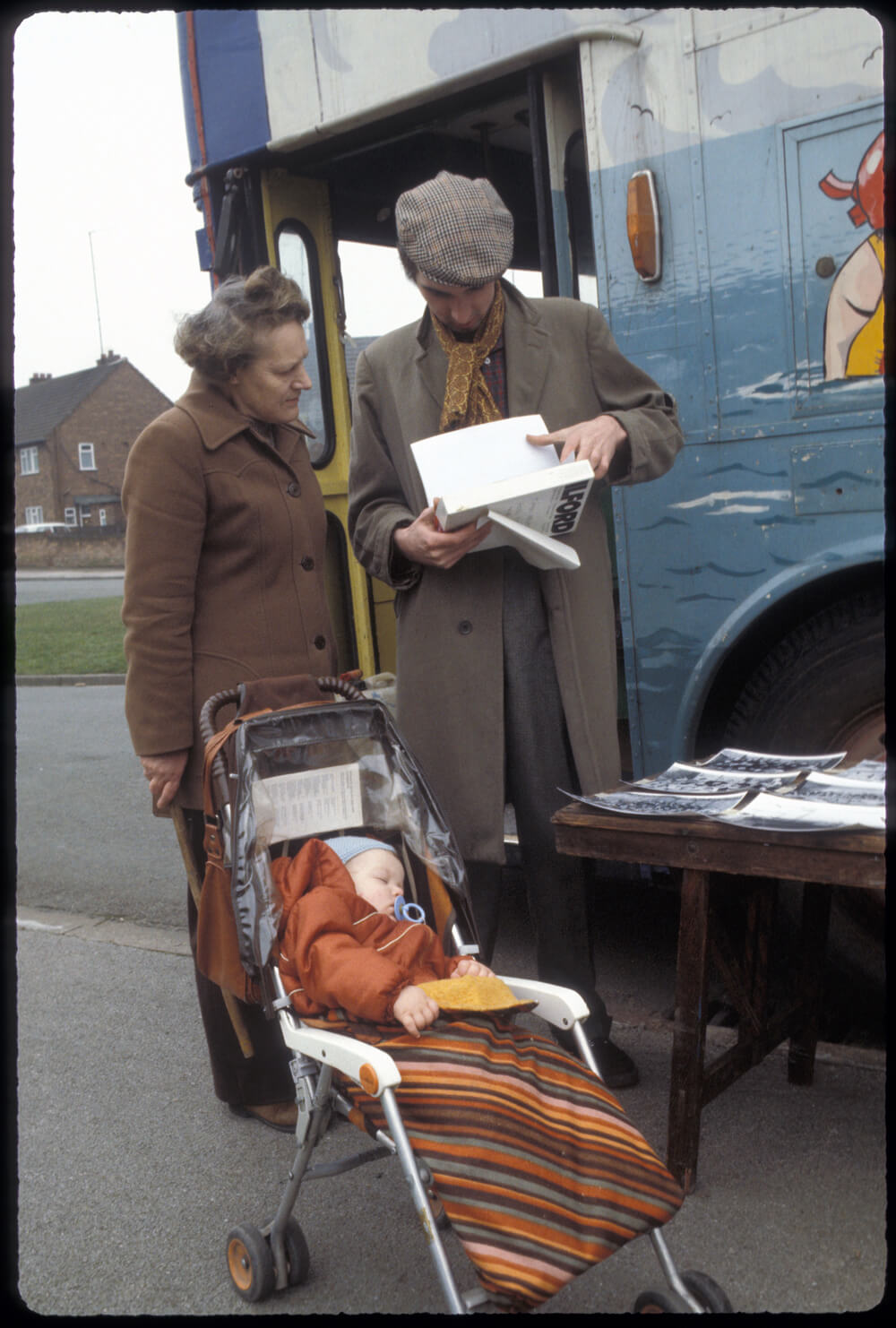

The company had worked in Tipton for a number of years, mostly on children’s play activities, particularly with Oval Road Tenants Association. In 1983, they launched a project aimed to involve people of all ages, to create a picture of Tipton. Cynthia Woodhouse (a former English teacher), Derek Jones and Peter Chaplin, both visual artists, led on the project, taking the Bus around different parts of Tipton. Working with local libraries, they had a selection of local photographs of the area from over the decades to stimulate discussion and commentary. The bus acted as both an exhibition and meeting space. They set up a portrait booth to take photographs of people, printing these up and bringing them back as a temporary exhibit, then inviting participants share their experiences of living in the area, to sit and talk and draw. A number of volunteers supplemented the team, some from local art colleges, some from secondary schools. Working with the material, they creating a street show with musician Dave Rogers from Banner Theatre, taking this back to a number of locations, along with photo materials.

‘We were overwhelmed with the amount of information gathered and toured the Bus again in 1984, this time with a short performance based on the 1983 tape recordings, meeting new people and many previous contacts, leading us to work together on the production of a publication. Time and financial constraints, plus the volume of the writings and tape recordings, led us to concentrate on just one area, childhood. What follows is not intended to be a formal history, rather it is people’s memories and impressions of their past, told in their own words.’

– Cynthia Woodhouse, from her introduction to the project, 1984.

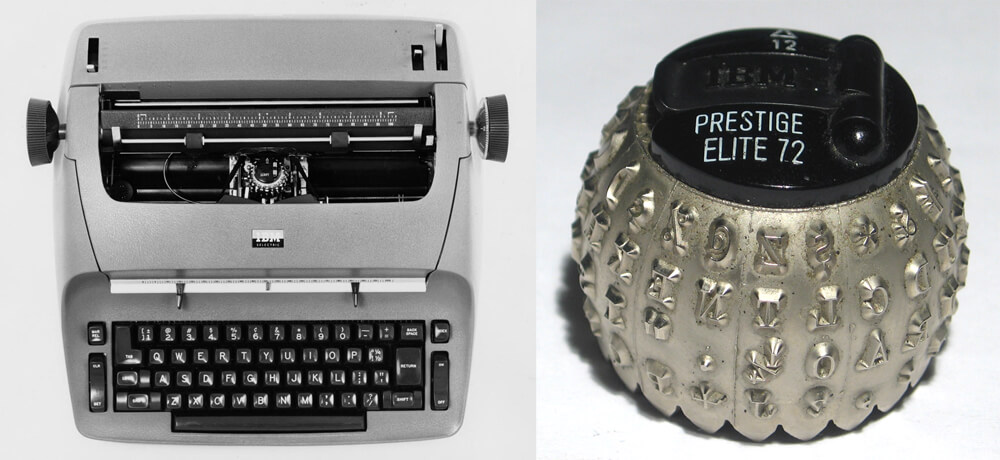

They created an A3 publication; selections from transcripts were typed up on an amazing IBM Selectrix II typewriter. Originally promoted as ‘the best thing that’s happened to typing since electricity!’ this was an electric typewriter with a removable font ball, which gave you the opportunity to use italics. Jubilee had three fonts to work with (American Typewriter being their favourite, which we’ve used for banner headlines on this website). The typewriter had been donated to the company by Admin & Legal Services Department at the town hall in West Bromwich, when they were getting equipment. Text and photos were then cut and pasted together and photocopied (A3 photocopiers also being a new technological revolution.) They were sold for 70 pence a copy; no copies exist in the archive, but the original hand made artwork has been preserved in all its glory – cut and pasted text, heavy use of the correction fluid Tipp-Ex and headlines made with Letraset.

Mickey Mouse is dead,

He died last night in bed,

With a five pound note,

Wrapped round his throat,

And this is what he said…

Red, White and Blue,

Diana’s in the loo,

Prince Charles has lost his underpants

An’ don’t know what to do.

– Children’s playground rhyme,

collected from Glebefields School.

Sometimes I want to move, but other times I’m glad that we haven’t. I’ve grown up with all the people round my street and when I come out they start chatting and everything. If I moved anywhere else I wouldn’t know people and what they were like. I like our street, Dunkirk Avenue. Before me and me mum were always on at me Dad to move, but one night I dreamed I was moving and I woke up crying.

– Comment from exhibition boards.

The value of this kind of project? Fostering trust and creating bonds, beginning discussion, asking critical questions, thinking of how the future may be, seeking to engage and foster civic participation. Told in their own words is the key point. Oral history, in particular, explores stories on the margins, of personal relationships, domestic lives, of the local and specific, trying to understand the hidden lives of people, the ‘unofficial’ histories of the working class, the migrants, the oppressed. There has been much criticism that oral histories are unreliable, as they focus on memory not fact, distorted by nostalgia, exaggeration or deterioration of mental faculties but they have served as an important ingredient in community arts work, partly because in the modern world (to borrow from Paul Kingsnorth again) ‘the small and the local, the traditional and the distinctive were being stamped out by the powerful, the placeless and the very, very profitable.

As part of the Jubilee Archive project in 2014, artist and film-maker Geoff Broadway was commissioned to work with members of Tipton Local History Society. Using materials in the archive as a starting point, reflecting on these themes of memory and community, over a period of a few months, he traveled around Tipton meeting local folk, collecting their stories and sharing their photographs. The result is a short film which celebrates the town, remembers the past and looks forward to the future. View the film below.