In the 1980’s, the children that Jubilee had worked with on summer playschemes were now teenagers. By 1984, youth unemployment (covering the 16-24 age range) stood at a record 1,200,000 – more than a third of the total unemployment count. Areas like the Black Country were particularly hard hit, with the industrial base of the area devastated, as locally-significant businesses closed, unemployment continued to rise. As the crisis worsened the figures were ’massaged‘ – unemployment was technically eradicated among 16 and 17 year-olds in the 1980s simply by making it illegal for jobless school leavers to claim unemployment benefit.

Many were now on Youth Training Schemes (which usually lasted for six months), run by the Manpower Services Commission, brought in by the government in 1983 to alleviate unemployment. Many saw this as cheap labour (which it often was). Others saw it as an opportunity to give young people some genuine skills. The new centre for the Community Association of West Smethwick was built by local youth people on MSC schemes. Jubilee had two MSC trainees in 1979, but then looked for different ways to engage youth people.

Their 1980-81 annual report made their views clear. ‘No-one involved in community work at the moment can fail to be confronted with the consequences of unemployment. With over 15% unemployed locally and almost 6000 young people in Sandwell without proper jobs, all voluntary and community organisations are having to re-assess their stance in relation to such problems. Although some have responded by sponsoring an increasing number of MSC schemes, few young people are under the illusion that jobs will be offered at the end. Neither are they persuaded that clearing graveyards or stacking supermarket trolleys on £23.50 a week will provide real training for the future. Believing that it is not enough and may well be misleading to commit the company’s resources to this kind of approach, Jubilee has made no plans to sponsor another MSC scheme in the current year. This report reflects a perhaps broader and more determined emphasis on working with the unemployed. Public expenditure diverted into unemployment benefit and MSC training effectively removes our ability to offer real training for real jobs.’

For example, it secured a series of 2 year apprenticeships funded via the Gulbenkian Foundation. It also worked extensively with young people on training programmes which were devised with young people around their specific interests and needs, whether this was the organsitional skills needed to organise a festival, learn a desktop publishing programme, run a promotional campaign, or issued based work.

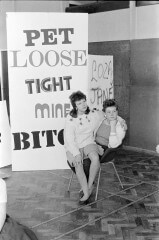

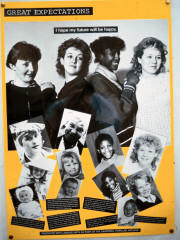

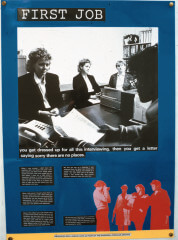

Other groups like Telford Community Arts and Birmingham Film & Television Workshop operated on similar lines. Over in Telford, Carola Adams and Leah Thorn, with Graham Peet and Jonnie Turpie, facilitated the activity of the Madeley Young Women’s Writing and Design Group. The outcome of the collaboration was a set of 9 posters, developed around the experiences of the young women involved and underpinned by an inter-generational and collective ethos. This work was widely distributed and well known. Johnnie and Graham went on to work with Birmingham Film and Video Workshop to produce a film ‘Giro – Is this the modern world?’ (1984, 45mins). Working with a local youth group DHSS (Dead Honest Soul Searchers), the film explored ideas around work, labour and the benefit system in the context of the mid-1980s.

Youth festivals, media workshops, training events led to deeper connections and longer term work with groups. For example, Dee Murphy from Jubilee worked with a group of young girls in the Greets Green era, who later named themselves Fifteen Plus, and the Smethwick Spades AKA Crazy Spades. Members of both groups became involved in organising events such as summer celeabrations programme and served on Jubilee’s management committees as youth representatives.

‘We’ve talked, taped, used drama, music, argued, laughed and had good times together. There was a youth festival at Chat’s Palace in London last April. We were the only group outside of London who were invited. We already had one piece ‘The Engineer’ but we decided to work on a longer show ‘Girls Can Do Anything’. We did this in a totally different way, and although it was strong it had a funny side to it. We had a great time and many people enjoyed and were impressed by our performance. The kids from London came up to Birmingham for the festival ‘Youth Matters’. This was when two new members, Dawn and Maureen, joined our group. We were sick of being known as the Greets Green Girls and after many arguments we decided on Fifteen Plus. We think it’s a positive name for the group. We were asked to perform to the youth leaders who were supposed to be interested in working with girls. It was an unforgettable experience after being told we were being brainwashed because of what we believed in. We wrote our own leaflet to help with publicity, to give more information about us. At one performance we met a journalist ‘Jane Dodge’ – this was a breakthrough as she managed to get us on Radio West Midlands. Being an all girls group we share the same experiences and back each other. We are more confident and positive. Now we don’t back away any more. We stand up and fight for our rights.’

– from interview for West Midlands Arts magazine ‘Report’ youth special, 1985

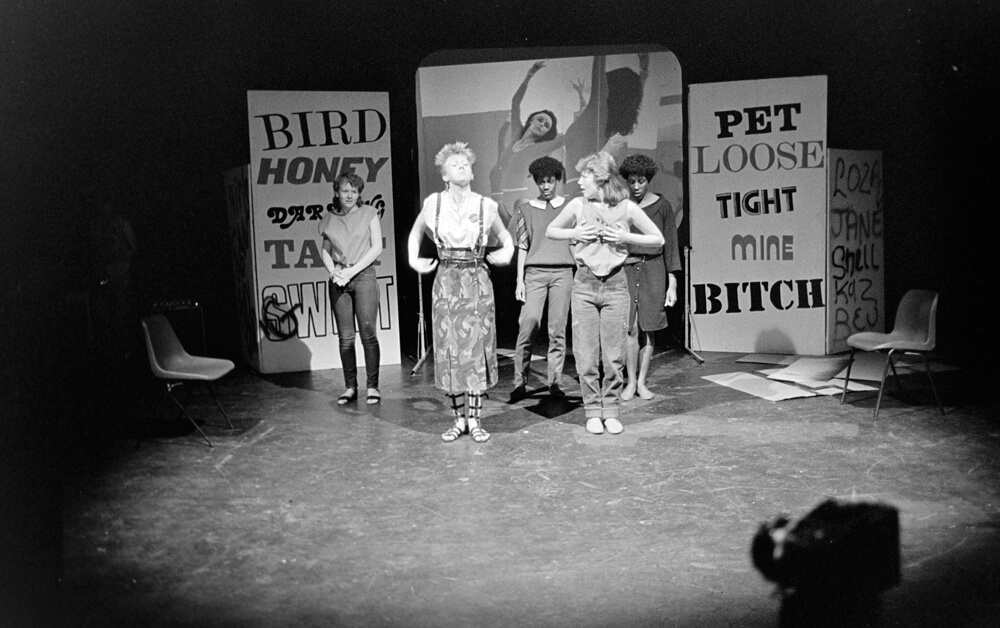

The ‘Girls Can Do Anything’ show ran through a series of sketches and songs about everyday experiences with a series of back projections. It was first performed to a ‘friendly’ audience of women at Banner Theatre in Handworth, then reworked it. ‘I used to hate drama at school. I used to stand there and go red in the face. I don’t feel this group will laugh at me.’ They performed it at a number of youth festivals over the next 18 months, and then produced a small touring exhibition of photographs and text called ‘Talkin’ About Our Generations’. The material was devised from interviews with a range of older women. They also participated in a range of tailored workshops to extend their skills – one learned to play guitar. They even set up a self-defence class for girls in Greets Green.

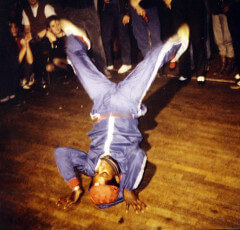

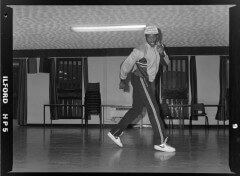

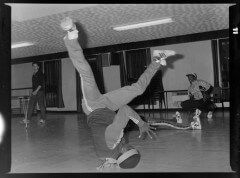

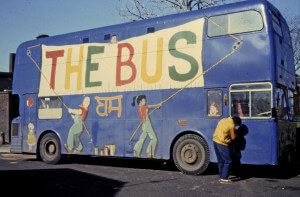

Artists from Jubilee first met the Crazy Spades at a festival to celebrate the opening of a new community centre in Smethwick. After watching the procession with the bus, they invited Jubilee into a back room and said: ‘We’ve seen what you do. This is what we do’ and proceeded to give a demonstration of body popping and breaking (This was several months before ‘Hey You, the Rock Steady Crew’ hit the charts and brought street style to the world.) What they initially wanted was a space to rehearse. Through Jubilee contacts, they had a regular evening slot booked at Menzies High School, the only school in the borough at the time with a dance studio with full-length mirrors. They participated in the 1984 May Day Fireshow and went onto to devise a 40 minute dance performance based on the idea of ‘A Day in The Life of Smethwick’, a combination of pre-recorded beats, two live musicians on guitar and keyboards, dance moves and storytelling, with a filmed background of contemporary news footage (of riots, police harassment and the miners strike). While some members participated in the Summer Celebrations programme, others organised dance workshops.

‘A lot of us train before we come out of the house. I always do. If I know I’m on tonight I’m always stretching in the day, bend your back up and everything, handstand against the wall. My girlfriend’s brother… well my girlfriend’s white and he’s about 30 and he watches me doing my bodypopping in front of the mirror and he says ‘Show me some of that, Frank’ and he’s a bit old and stiff, so I have to show him what to do. So you loosen your arms and loosen your body first and you’ve got to move your arms up and across sort of thing. I show him how to do it slowly and I say keep practicing every day, just moving your arms across and you’ll learn to get it down your body. And he tries to learn it, so when we go to a disco and I’m doing it, he tries to do it with me, in front of the people. When I was dancing I was the only coloured chap, cos it was in the Dudley area, and they’re watching me do the bodypop. They’ve never seen it before. When you see something like that right in front of you, it’s different than seeing it on the telly, so they get amazed when they see somebody doing it and they want to learn it.

It’s a bit of an achievement, a memory, when I’m a certain age I can look back and say ‘this is what I done’ sort of thing to my son, you know. I’ve achieved something, teaching people. I can sit back and say I’ve had a full life doing this and that. You can say when you’re old I’ve done all this lot and now it’s your turn, so live your life to a good potential, rather than going to the pub every day for 25 years. You’ve achieved something.’

– from interview with Franklin for West Midlands Arts magazine ‘Report’ youth special, 1985

Their philosophy with this work was not simply to engage with young people, but to encourage them to be involving in the planning of arts activities, sharing with them the tools of production as well as the ideas. Frank, quoted above, wanted to set up a driving school, that was his ambition. He was expressedly interested in how the management committee of Jubilee was run, how were decisions made, how were things recorded, what was a budget, what was cash flow – very practical things. And he came onto the management group for a while to learn about those structures.

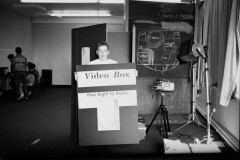

In 1987, Sylvia King and Wes Webb, wrote about this: ‘Rarely, either, do we allow young people to be part of, let alone control, the planning of the arts. While there are many drama workers, painters, video-makers who are skilled at giving over their medium to young people, they often arrive at a youth club or group of young people apparently out of the blue. We have to find ways for young participants in arts activities to have control, not only of the camera, but whether the camera arrives or not. Young people have the right to their own cultural expression, a right to define what ‘the arts’ are. This implies that the decision making has to be decentralised from bodies like the Arts Council, the Regional Arts Associations, and local authority youth officers. We can avoid parochialism if we give young people access to the networks of people and organisations that we use.’

You’ll find the full article in the Resources section.

The Crazy Spades AKA Smethwick Spades young group. First part of performance captured by audience member at Youth Arts Festival at the Triangle, Birmingham, 1984.