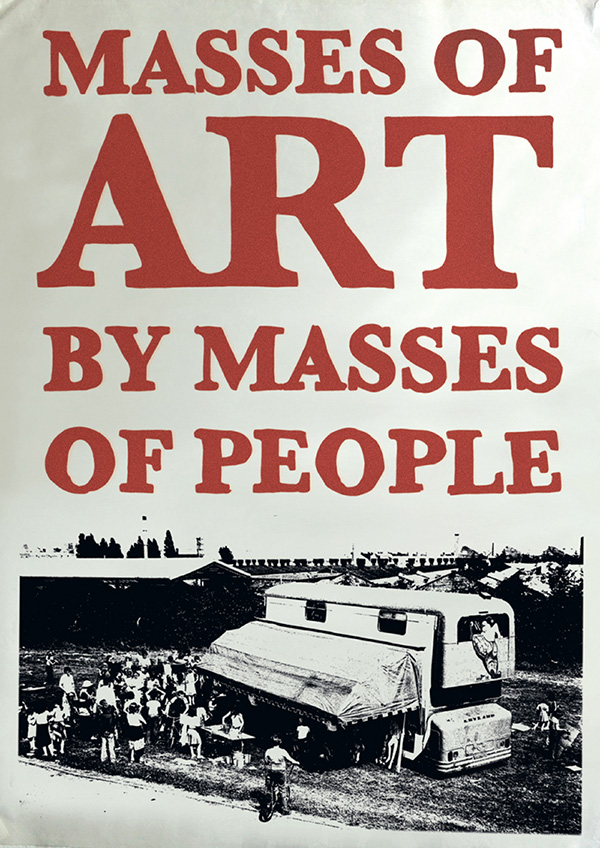

At the end of the 19th century Tolstoy published a book, ‘What is Art?’ It had taken him some nineteen years of writing and rewriting and he was never quite satisfied with it. He concluded that the art of the future would not be that ‘transmitting feelings accessible only to members of the rich classes, as is the case to-day’ but that which would bring people together ‘in brotherly union.’ Art would be accessible to all and artists ‘and the artists producing art will also not be, as now, merely a few people selected from a small section of the nation, members of the upper classes or their hangers-on, but will consist of all those gifted members of the whole people who prove capable of, and are inclined towards, artistic activity.’

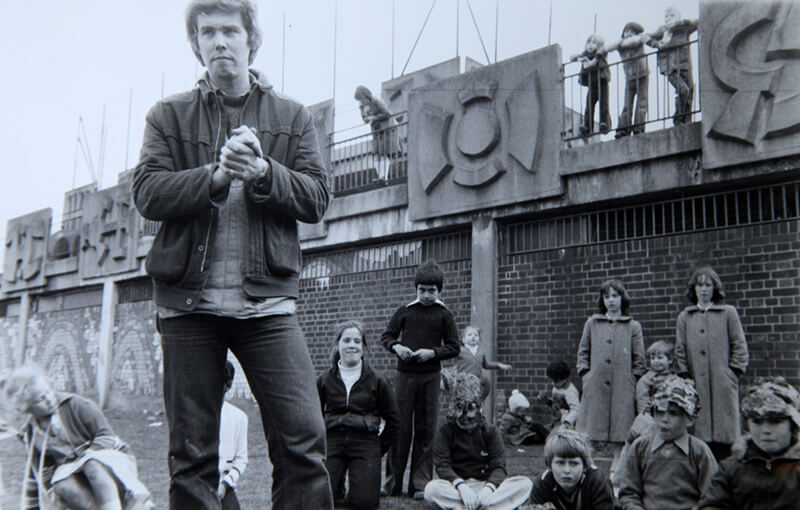

Some 70 years later, a group of young people in Sandwell, part of the then blossoming community arts movement, asked a different kind of question: Who is Art For & Why is it Only Found in Certain Places? They founded Jubilee Theatre and Community Arts Company in 1974, to explore new methodologies and new levels of participation in art. Over the next 20 years they raised over 2 million pounds for local arts and community activity, working with 850 different groups, reaching over 200,000 people. Their name went through a few iterations – ending up simply as Jubilee Arts – or as locals were fond of saying ‘The Jubilee’.

They were inspired by the radical politics and idealism, educational and cultural changes of the 1960s. Their antecedents might well have been the ‘Fun Palace’ ideas of theatre director Joan Littlewood and architect Cedric Price (who saw arts spaces as a ‘laboratory of ideas’ and ‘a university of the streets’); the famous pronouncement of Joseph Beuys that “everyone is an artist”; the Arts Lab movement; the experimental theatre of Ken Campbell; concepts of co-authorship, ephemeral events and ready-made; the ‘cultural animateurs’ on the streets of Paris ’68; and not least Jennie Lee’s historic 1965 White Paper, ‘A Policy for the Arts: The First Steps’, which proposed to put art back in local communities. From the beginning Jubilee’s creative work was very much rooted in the local and the specific – at its core was an examination of identity, questioning and challenging our common understandings of art, expertise and community.

1974 was a year of major reorganisation of local government in the UK; the old boroughs of Warley and West Bromwich were amalgamated into the new Metropolitan Borough of Sandwell – with a population of nearly 300,000 people. Jubilee started up with two grants of £75. It had the loan of a disused branch library at the back of a municipal tip, a kitchen for a darkroom, an old ambulance with 2 months motor tax, 4 kazoos, several boiler suits and an outside loo. (Incidentally, the following year the world’s very first computer store opened in Santa Monica, California.)

There were other groups starting up in the region at the time, among them Telford Community Arts, or in Birmingham, Trinity Arts and GASP (Group Art Spectator Participation, who later became SPAM – Saltley Print and Media), each with their own specialisms and neighbourhoods. Prior to this, there had been Birmingham Arts Lab, founded in 1968, an experimental space that ran until 1982, and the Midlands Arts Centre for Children and Young People, founded in 1962 – which is now the MAC.

‘Friends and Allies’ was the title of a community arts conference held in Salisbury in 1983. The friends and allies of Jubilee were not just these other artists grappling with myriad ideas of social engagement, but health workers and trade unionists, members of tenant associations, informal groups of young people, women’s groups, Black and Asian associations living together in this densely populated urban area. There was a large DIY element to the work of this period, both in materials and process, even a kinship with the punk rock ethic. It also shared many of the characteristics of work from the Fluxus period, such as using readymades, simplicity of construction and materials, improvisation and an interest in events, a willingness to experiment with creative tools and ‘happenings’ rather than creating stand alone objects.

Between 1974 and 1994, Jubilee methodically captured and documented all aspects of their work with diverse communities. As a group they left behind a considerable repository of archival material. This material provides a snapshot of social movements that had began to spread out across the country in the early 1970s – in terms of giving voice to the local community, something which had not happened before this period. Its value lies in the authentic experience it captures – social documentation and history from a community perspective, made by people themselves. It also provides a narrative of a cultural practice, which sought to put tools in the hands of local communities by engaging directly with local issues and concerns, alongside the representation of an increasing diversity of both working class and ethnic voices.

Jubilee was renowned for street theatre, play schemes, community festivals, murals and innovative Theatre-in-Education projects, and much of its early work made use of silk-screen printing, analogue photography, reel-to-reel video, Super 8 film, an electronic golfball typewriter and a Gestetner scanner. In 1978, they acquired a double decker bus (the first of three), which they used as a mobile arts centre. At the beginning of the 1980s they were involved with community campaigns with Tenants’ federations, Trades Councils and trade union groups, from the Indian Workers Association to Rock Against Racism. In the late 1980s – in response to a highly controversial feature about Sandwell in the Sunday Times Colour Supplement titled ‘Ghetto Britain’ – Jubilee launched a series of innovative photographic projects under the umbrella of ‘The People’s Portrait of Sandwell’. By the mid-1990s their facilities expanded to include a recording studio, a video edit suite, two photographic darkrooms in the borough, and were at the leading edge of community publishing and the possibilities of interactive multimedia. In this respect, they won a Health of the Nation Award for their interactive production ‘Sex Get Serious’, and the IBM Community Connections Award for ‘Lifting the Weight’, a game aimed at male offenders, either in prison or on probation, created with Geese Theatre (which also picked up a BAFTA).

From the outset, though their roots may have been in drama school, Jubilee operated as a multi-media team. Multi-media then meant that as a photographer you might be called upon to work with break dancers – and learn some moves too – or a mural worker might work with a poet. It was ‘mix and match’ community arts – whatever was the right tool for the job, you would use it.

In 1948, members of the United Nations declared a ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ which stated:

‘Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community.’

Jubilee, like many other arts organisations of that period, sought to ensure that the United Nations Charter statement became a real choice for people and remained a guiding principle in their work.

It was their belief that cultural diversity is a positive social value, to be preserved and nurtured, and that democratic participation is an essential component of cultural life – as was a fair distribution of cultural resources throughout society.

Much of their work was an examination of identity – who are we are where are we going – seeing this as the basis of all art making. In later years, as a group they worked internationally, finding that the expression of their local experience had a potency and a resonance of much more than local significance.

(Note: ’Culture, Democracy and the Right to Make Art’ by Alison Jeffers and Gerri Moriarty (Bloomsbury, 2017) provides an overview of this body of work carried out by artists in communities in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Metropolitan Borough of Sandwell lies at the centre of the largest provincial conurbation in the UK, surrounded by Birmingham, Walsall, Wolverhampton and Dudley. It is an area of strong community loyalties and cultural diversity. It is one of the four boroughs identified as ‘The Black Country’ with a population of 1.2 million.

Sandwell grew out of six towns – Wednesbury, Smethwick, Rowley Regis, Tipton, West Bromwich, and Oldbury – whose growth were stimulated by the Industrial Revolution of the early 19th century. By 2016, the borough has a population of 319,500, with diverse cultures including those of Black African, Black Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Yemeni peoples, alongside more recent migrants from Central and Eastern Europe. 34% of residents are from these minority ethnic communities. This compares to 20% in England and Wales.

As a result of the industrial past, and with shifts from a manufacturing to a knowledge-based economy, Sandwell has undergone a great period of transition. Manufacturing still accounts for 11% of jobs in Sandwell, down 8% in the last decade, compared to 9% in Great Britain as a whole. Former industrial land – often contaminated – meant that in the early 90s it had the highest proportion of derelict land outside of London, but extensive reclamation programmes have reduced this by over half.