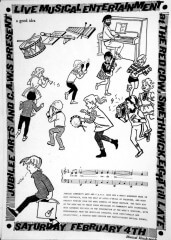

The Red Cow is a popular pub on Smethwick High Street. As long as we can remember, it has always had a life-sized red cow on a plinth outside. I has been used a venue for several types of events, by Jubilee and other organisations. Rock Against Racism gigs, a performance by a 15 piece Parisian folk group Passacaille alongside Pigtown Fling, a benefit night of poetry and songs to support the Raindi Strikers, meetings of the Indian Workers Association… Then one Saturday night early in 1984, the upstairs function room was packed solid for a singular performance by a group of musicians (and a few non-musicians) who had never played together live before, who had only met six days before in a community centre on the West Smethwick estate AKA The Concrete Jungle.

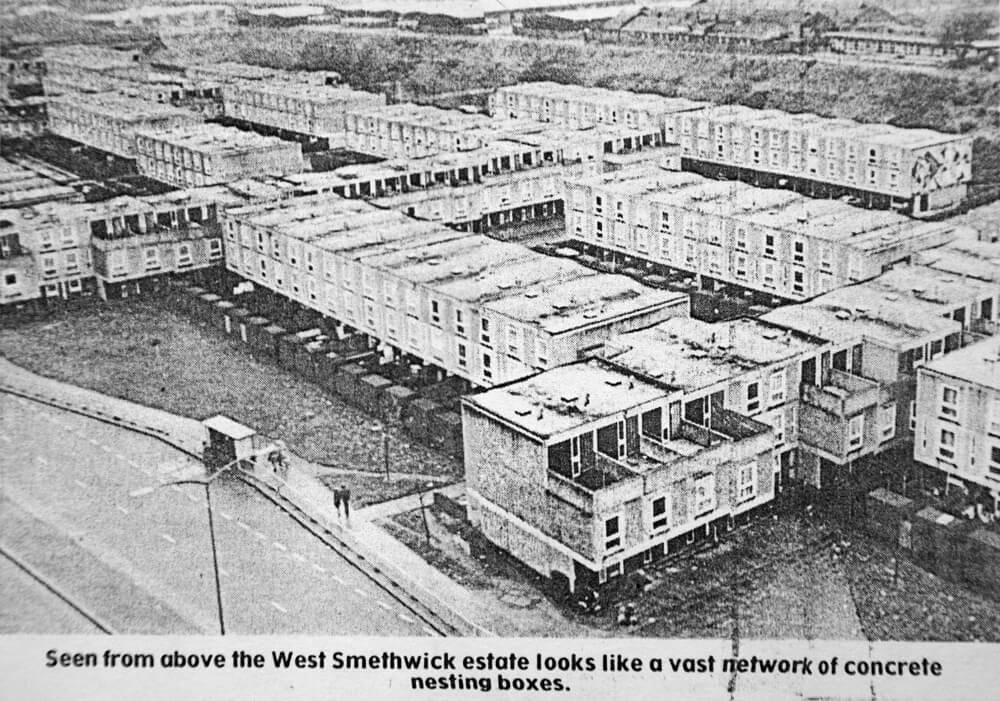

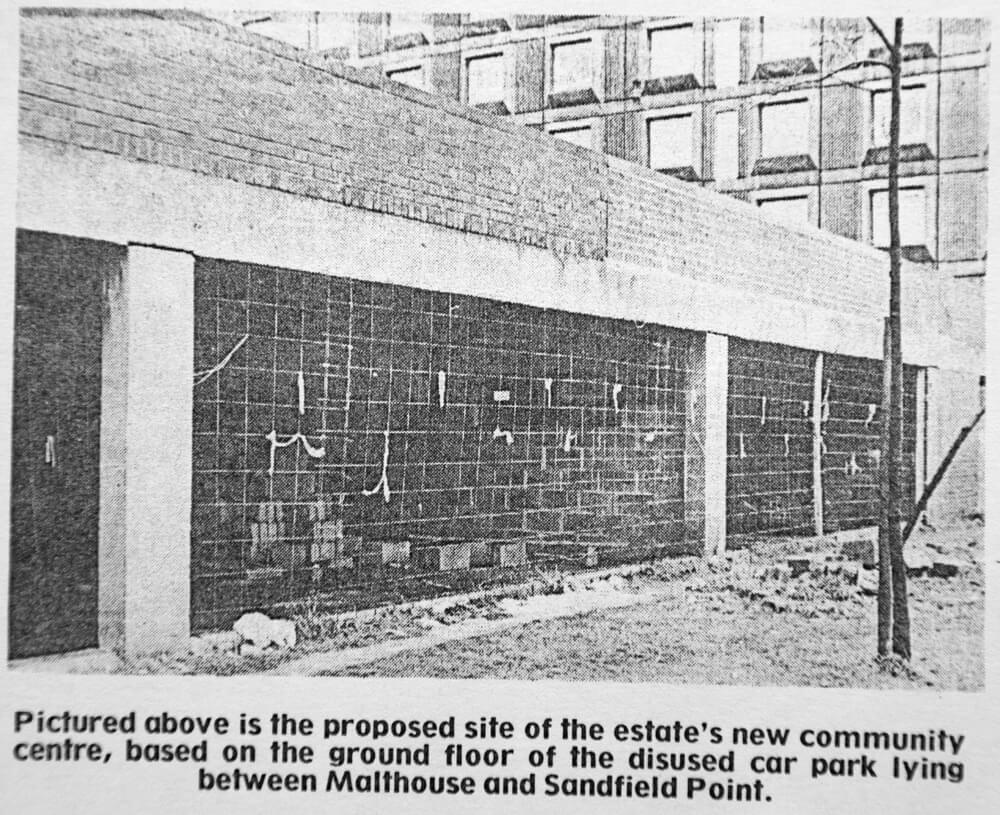

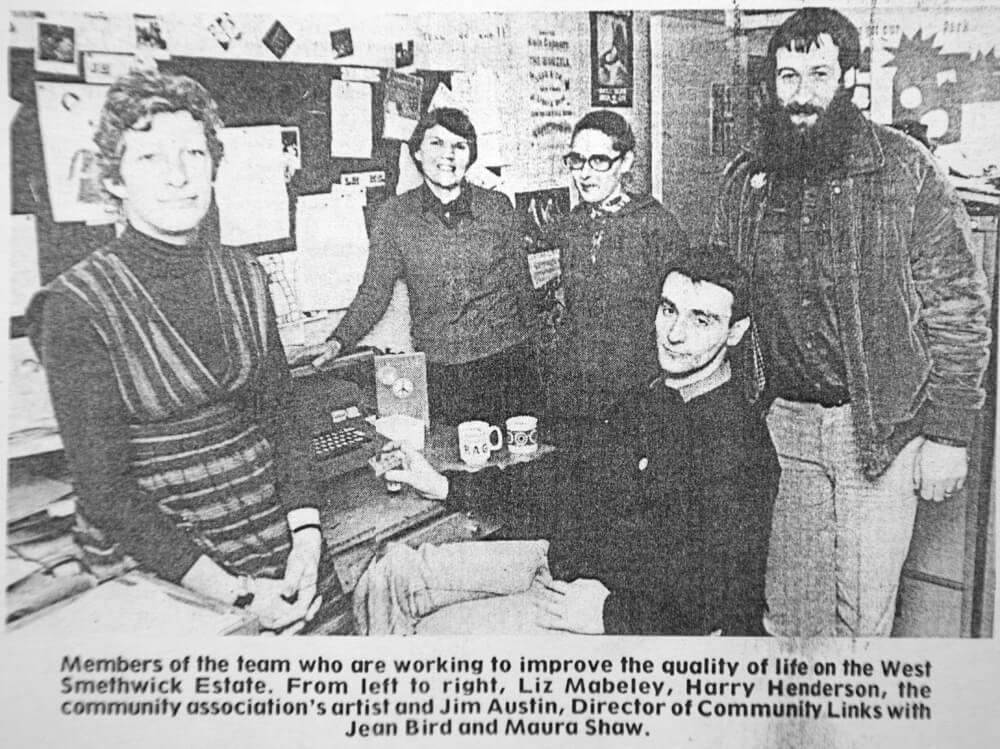

The West Smethwick was quickly built from in the 1960s to deal with housing shortages, using the Bison industrialised building system of precast concrete. Hemmed in by a dual carriageway, the railway and the motorway, the estate became known as an area with a large number of social problems lacking any amenities. It was ‘a kind of no man’s land’, as described by the Director of Community Links, Jim Austin. Community Links began life as Home-School Links in 1974, to develop links between home and schools in the area, identify problems and work with residents to seek solutions. Jim, a former teacher, was keen to use the arts in the work in West Smethwick. He knew the work of the Jubilee group, as the Spon Lane playhut had been used for theatre and playwork, and he had joined their board of management. In 1977, the Housing Department donated one of the empty houses on the estate so Home-School Links could be based there. They produced a local community newspaper called ‘Gerrof’ and had secured funding that year for a full time community artist to work with them. Harry Henderson, who had previously worked at Trinity Arts in Birmingham, and also with GASP (Group Art Spectator Participation), developed a number of programmes on the estate, linking up with Jubilee. They created murals on passage walls between the estate blocks, organised a portable cinema touring locally to schools and in 1979 relaunched themselves as Community Links, also establishing an independent community association. They operated a photographic darkroom out of Nelson Court, working with Jubilee and by 1983 had built a new community centre at the foot of the tower blocks, Sandfield and Malthouse, utilising an abandoned carpark.

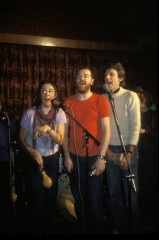

This became the venue for the music workshop, as Harry (who played a bit of acoustic guitar) was keen to expand the portfolio of arts activities on offer. The project was a collaboration with Jubilee, who were working with Cultural Partnership on developing a local May Day Fireshow which would have a band, so this was an opportunity to test the waters and recruit interested local musicians. With Louis O’Neill as lead tutor, the workshop was planned to explore different repertoires, styles and ways of making music. While musicians with some ability were at the core of the workshop, open sessions were planned in order to recruit non-musicians – “If you can learn a couple of notes, make some noise, bash a percussion instrument, you can participate.” It was set up as a training programme, an intensive workshop designed to introduce musicians of varying skill levels to community arts techniques – this included open workshops for children and young people to put ideas into practice. Louis was our guide – brilliant at organising, mentoring and music making. That first music workshop week attracted around 30 participants, all with very different styles of music making – whether, rock, punk, blues, folk, funk. Over six days they created a whole series of original genre crossing songs, which were then performed over 90 minutes at the Red Cow.

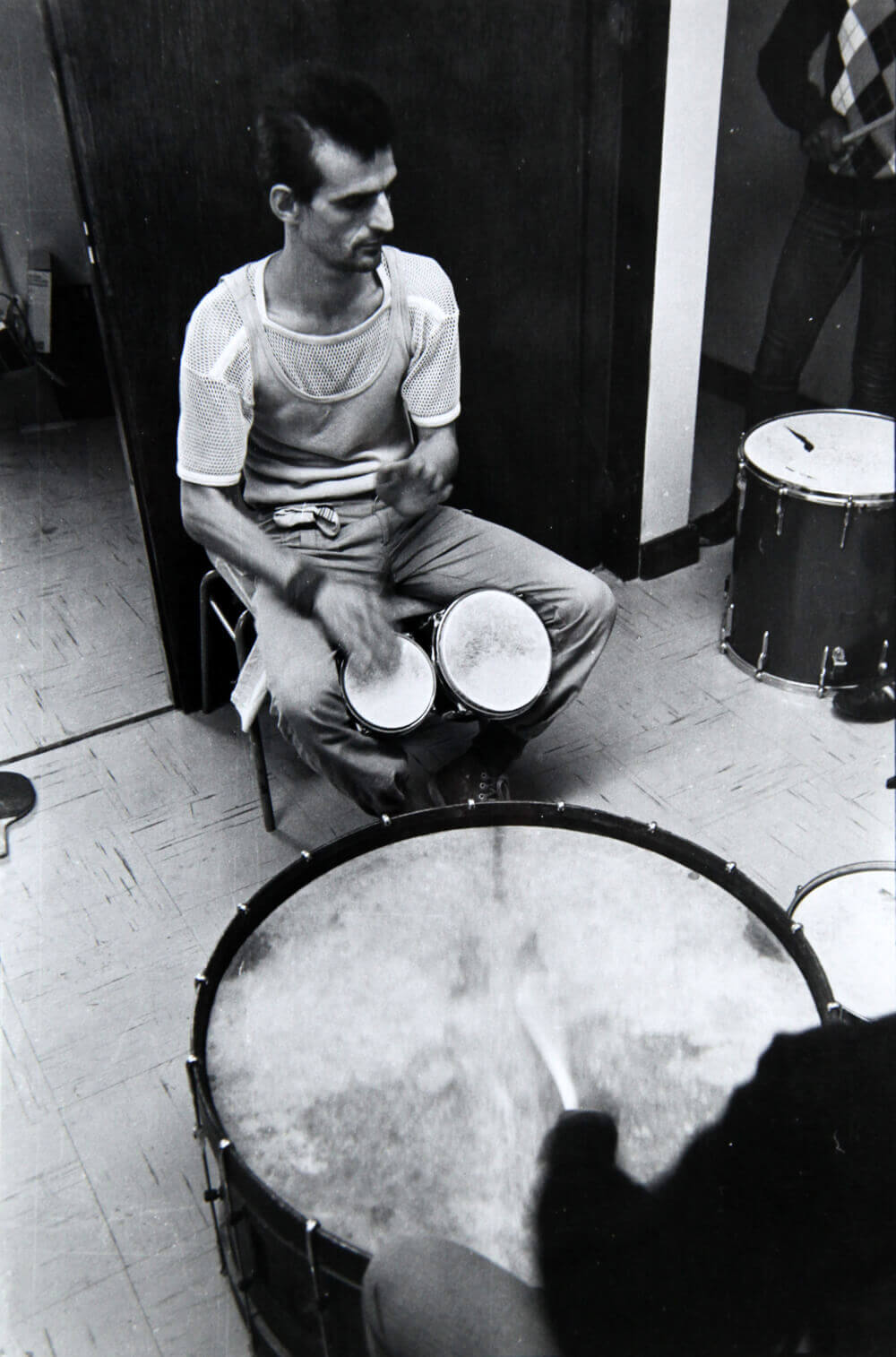

Ron Collins, one of the original workshop members recalls: “I was generally looking for work as a musician. I was unemployed at the time. I was invited over to Jubilee by Cynthia. So the gig at the Red Cow was the first thing I got involved with. My developing working approach started with the belief in the universality of music. For example, sea shanties or work songs, which are universal, from all over the world, which facilitate work or the gathering of community strength to perform a particular task. My particular skills, voice and percussion, going back in time are the universal things people would have come up with before anything else, banging on rocks and logs before drums were fabricated and they would be vocalising. That was the precursor to any invention of instruments. That was the luck of my musical skills because I’ve found it’s easy to engage whatever group on that level; if you get into a guitar or keyboard then people have to put in the work, have to practice, and get up to a standard to share with other musicians and build a community around you. And you’ve all got to operate on an understandable level. Once you’re into that realm, then you’re beginners and intermediate and super duper musicians. With vocal and percussion you can demonstrate the foothold that anyone can get into music making and sing about things that concern your community. We kept an eye on being as multicultural as possible while acknowledging your own heritage. It was inspiring.”

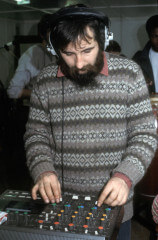

The participants then went on to perform at the May Day Fireshow in Victoria Park, devising a whole new set of material to accompany the processions and theatricals. Then, as well as continuing to meet weekly at the community centre, members of the workshop also provided the backbone of a barn dance band for Jubilee Summer Celebrations in subsequent years, and participated in several festivals and events, including an annual showcase ‘Soundstage’ at the Sandwell Show. They were also booked for social events across the borough and were invited to participate in workshops with Cartwheel Community Arts in Rochdale for their own November Fireshow. The workshop went onto run recording sessions at the community centre, to give an insight into techniques in recording a song and to explore the roles of technology and producers.

Members also went on to take up training placements with specialist music projects around the country and established a women’s music project, among several other projects and shows.

Ron Collins again: “I remember being involved in other workshops at Jubilee, when they were promoting a live music programme – Bolivar, the Latin American one, and the African one, Taxi Pata Pata. What I gleaned from those was feeding back into Smethwick Music Workshop.

We used to meet up a couple of nights a week in the CAWS community centre and get the equipment out and various people would participate. We’d put on events in the building, and we’d also take it out to a few different places. I think Jubilee at the time were trying to break out from being a group using the visual arts, and we helped do that, working with young people and older ones, playing music. We’d then feed into their other work, like the summer festivals. With Pete Yates from Banner Theatre we created a dance band for the barn dancing for those Summer Celebration events with the Bus. That was nice for me, also creating the music soundtrack for the shadow shows, improvising in that way, the need to be spontaneous. I miss that. But we’d get besieged by the kids sometimes. I remember at Hamstead getting bricked by the local lads. That’s a political challenge, how you involved and engage with the local community while half of them are throwing bricks at you. By and large we pulled it off. Some places we went back three summers in a row because it was well received. Sometimes there were very few instrumentalists available and it was a job to put a full band together. I remember Kevin, who was calling the dances, saying to me, ‘Well, me and you and me Ron, we could do it, just the two of us, a caller and a drummer’, which was a slight exaggeration.

“The workshop had a fusion of music. World Music was what they were starting to call it – but it’s funny how people with Scots or Irish ancestry like myself are much more aware of their folk heritage than the English are of theirs. My particular skills, voice and percussion, going back in time, are the universal things people would have come up with before anything else, banging on rocks and logs before drums were fabricated and they would be vocalising. That was the precursor to any invention of instruments. That was the luck of my musical skills because I’ve found it’s easy to engage whatever group on that level; if you get into a guitar or keyboard then people have to put in the work, have to practice, and get up to a standard to share with other musicians and build a community around you. And you’ve all got to operate on an understandable level. Once you’re into that realm, then you’re beginners and intermediate and super duper musicians. With vocal and percussion you can demonstrate the foothold that anyone can get into music making and sing about things that concern your community. We kept an eye on being as multicultural as possible while acknowledging your own heritage. It was inspiring.”

“A lot of the songs we did back at the workshop related to a theme, whether it was housing or whatever. That was one of the joys and pleasures of it. You were working to a brief. It needed to be informed by community issues. You wanted to address an issue with a song. It wasn’t just ‘Oh baby baby, shake your booty aha la la blah blah blah’. I was open and my tastes were broadening. It informed my practice for a long time. I’m sure I’ve been marked, not just with music, by this idea that you can enlighten someone to a skill they haven’t got, or to let people know that this is possible, even if you thought to yourself it wasn’t possible.

I then went on to do a lot of facilitation workshops, mostly with people with learning disabilities. At the same time was doing the community arts stuff, there was period there was that famous Enterprise Allowance Scheme going on where the Government bunged you £40 a week and you tried to create your own business. I failed dismally like lots of people at that. But in the meantime I accumulated a lot of sessional work, whereby you’re visiting a lot of different places. It wouldn’t be allowed these days. I can remember doing an old people’s day centre, then I’d do to a disability day centre then I’d go to East Birmingham College, where they’d let me loose with a bunch of people, all in one day. It did inform my working practice ever since, so I was able to go in at their level, with songs they recognised and it led to a quite a long fulfilling career working with people, quite a few elderly, some recovering from mental illness, but mostly with those with learning disabilities. If you can help sometime find a skill they might think they haven’t got, let people know ‘This is it is possible’ even if they thought it wasn’t possible, that’s important. That’s the power of music.”

It was political, taking stuff to people, making people aware of something that might be their heritage actually, pointing things out. You’re keeping an eye on being multicultural as possible or necessary and as a part of that acknowledging your own heritage. This is something that still informs my personal life now.”

Ron can be seen playing drums in this video for ‘Rockin’ With Rita’ from 1986.

There were other initiatives, as Jubilee took on a musician Chris Jones, as a member of the team. He was involved in promoting events for Sandwell Arts Festival. In 1987, Owen Kelly came up to West Bromwich to run some music workshops. He recalls: “In the early 1980s, I was part of Mediumwave and one of our projects was Contagious Tapes. This consisted of a Tascam Portastudio and a rack of tape decks, and from this emerged 36 tape albums, all part of the C86 generation. At the same time, as part of this, I was making music with an imaginary band called Negrava, using an Atari ST, and program called (I think) Conductor, midi cables and a Yamaha DX9.

This led me to Jubilee to run some workshops on this new-fangled MIDI thing. Although this is now a rock-solid standard, at that point it was only just beginning to be used. The original specification was dangerously vague in parts and different manufacturers dealt with it in crucially different ways. This meant that patching a useful set-up together was a matter of experiment and patience, and there was no better way to do this than with a small group of like-minded people. The sessions at Jubilee did not produce much in the way of music, but that was never the point. They did result in everyone, including me, knowing more when the workshops ended than I had at the beginning.”

The workshops were promoted as: ‘Community Music – Midi’s and Computers: If you’re like me and don’t know what a synthesizer is, let alone the difference between a DX7 or a SPX or RX5, then this workshop will certainly be gobbledygook. Algorithms and sinewaves galore as Owen Kelly leads this session, based on some of his work at Mediumwave with computer generated music. Not a workshop for beginners – on the other hand, not for the Jean-Michel Jarres of this world either.

Some documentation from the first workshop week at the Community Association of West Smethwick and the night at the Red Cow.