The late 60s and early 70s saw an explosion of fringe, multi-media and experimental arts activity across Britain, of which community arts was one strand. In London a mural movement had emerged, as younger artists broke from commercial galleries in the capital to engage with a new public. As William Feaver wrote in the Observer of October 1977: ‘Over the past few years, though, an alternative murality has started to manifest itself on gable ends and in shopping precincts in Glasgow, Jarrow, Liverpool, Plymouth and elsewhere. Most of the recent British mural schemes have been sponsored by regional arts associations. The intentions are public spirited rather than remedial. That is, the paintings are designed not just to mask eyesores, but to take their place in the community, as rallying points and landmarks.’ People argued about ‘public art’ versus ‘art in the community’.

Jubilee’s Annual Report of 1979-80 stated that their brand of community arts was definitely ‘not just art in the community, an educational hobby, or simply a way of keeping kids (and adults) off the streets’. As a group they were beginning to expand their repertoire beyond theatre and playwork, with a banner created with Wednesbury Trades Council and then the first mural to be created in the area on the Yew Tree Estate. In 1978 Martyn Overs was employed as ‘Environmental Artist’ and set to work, following up the links made through Cynthia Woodhouse at Jubilee with the Bermuda Mansions Tenants Association, one of the significant tower blocks on that estate. Yew Tree, to the north side of West Bromwich, bordering with Walsall, was developed for municipal housing in the late 50s and 60s, and it was here that some of Sandwell’s first multi-storey flats were built (now demolished). It was also known as the home of two members of the heavy metal band, Judas Priest.

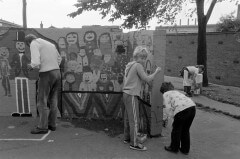

Martyn Overs recalls: “As a precursor to the main mural, I enlisted the help of children keen to be involved and painted three panels in a limited pallet of greens and blues on a smaller low single storey building set apart from the main wall. Whilst this was underway myself and Geoff Hunt, Chair of the tenants group, spoke to all the interested residents and I came up with a design that would keep the ‘goalpost’ theme as the kids had always played football against that wall. I wanted this to continue.

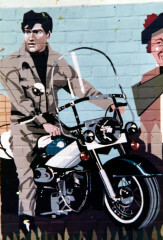

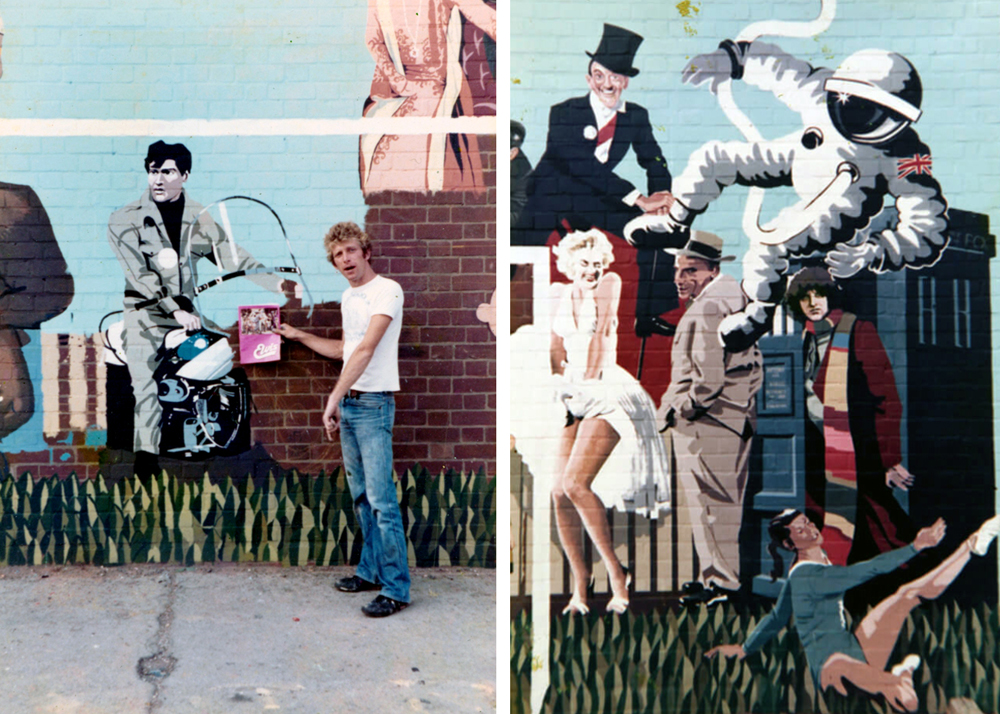

I am a huge fan of Peter Blake so the ‘famous people’ idea emerged. A census was taken as to who would be included. It may now seem a random selection of people but I tried to include suggestions from all walks of life and show the variety of ages and ethnicity that were involved at that time. The character voted for most was Elvis, hence him being centre stage. The children went for people such as Benny Hill, Charlie Brown, Tom Baker (then Dr Who), Dennis the Menace, Tom and Jerry, Punch and Judy and Superman. Marilyn Monroe, Tom Ewell, Groucho Marx with Margaret Dumont and John Wayne were the film star favourites of the residents. Sporting icons of the day (1978/79) included cricketer Derek Randall, hurdler David Hemery, Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci and our very own Birmingham athlete Sonia Lannaman. Due to the time restraint some extra characters were included taking images from some Players Cigarette ‘straight-line caricatures’ that someone had found… these were much easier to transfer to the wall. My own idea for inclusion was the ‘British’ astronaut (note the Union Jack on his shoulder).

Interestingly I dug out my old photographs of the mural (I have a day by day photo file of its progress) and underneath my name written on lower right corner by the Tardis and Tom Baker are also the names of the two assistants who helped me with it – Harry Henderson and Sue House… more interestingly is that it is dated 1979 and not 1978. In addition to mural work, I undertook poster design with Jubilee, including ‘Fight the Cuts’ (I still have a copy). I made many large papier-mâché puppet heads and props for various theatrical events and was involved in producing many cartoons which were used in the annual report of 1978/79.”

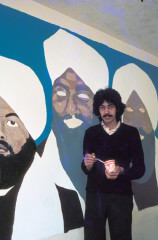

Pictured on the left, artist Martyn Overs holding the image of Elvis that was used as source material; on the right, a detail of the mural, with the British astronaut.

This first mural sparked discussions about what other improvements could be made in the locality, so the Tenants Association then fundraised for a five-week project to design and build a play structure, which culminated in a circus-themed opening celebration with Jubilee. The Chair, Geoff Hunt, was more than pleased: “We’ve had people coming forward for the first time to get involved – working on the structure, helping with materials. Some have joined the Committee and have begun to take part in other activities of the tenants association. It’s a great way to bring people together and helping them to appreciate each other’s skills.” Geoff Hunt later became a stalwart member of the Management group of Jubilee Arts.

Image on the left: Bermuda Mansions under construction in 1957, with Angela Tinsley (now Simcox) and her brother Keith Tinsley.

Kevin Hall: “Remember most my childhood living in Bermuda mansions.. always playing footy on fields outside flats… going on the park… remember painting the huge wall with all sorts of characters on them. Even painted goalposts on there. We had the funbus in school hols as well. Waterslides in the summer were great. Everybody felt safe those days.”

Loretta James: “Geoff Hunt getting a big sheet of plastic and a hose to make us a water slide and also the playbus. Great times as a kid, good community spirit.”

Comments from the Facebook page: ‘I grew up on the yte’

“There are some very good examples whereby we can say that community art has produced things which are worthwhile in their own right. Murals are one example. They seem to me to epitomise community art in the sense that a small group of people have actually joined in the work of artistic creation, and they have been able to do so because there was the kind of artist who could relate to such people, and wanted to enable them to work in that way. We are talking here about a small number of people, maybe 15, maybe 20, to whom this experience is of enormous value. But then you get bystanders over a period of time who belong to the neighbourhood or area, and find an identification with their particular group, whatever that is, through this work of art, either through knowing people who are working on it or through what it is trying to express.”

– Robin Guthrie (Joseph Rowntree Trust and Arts Council Chair of Regional Committee 79-81), interviewed in ‘Another Standard’ magazine, March 1982

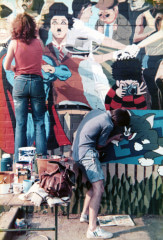

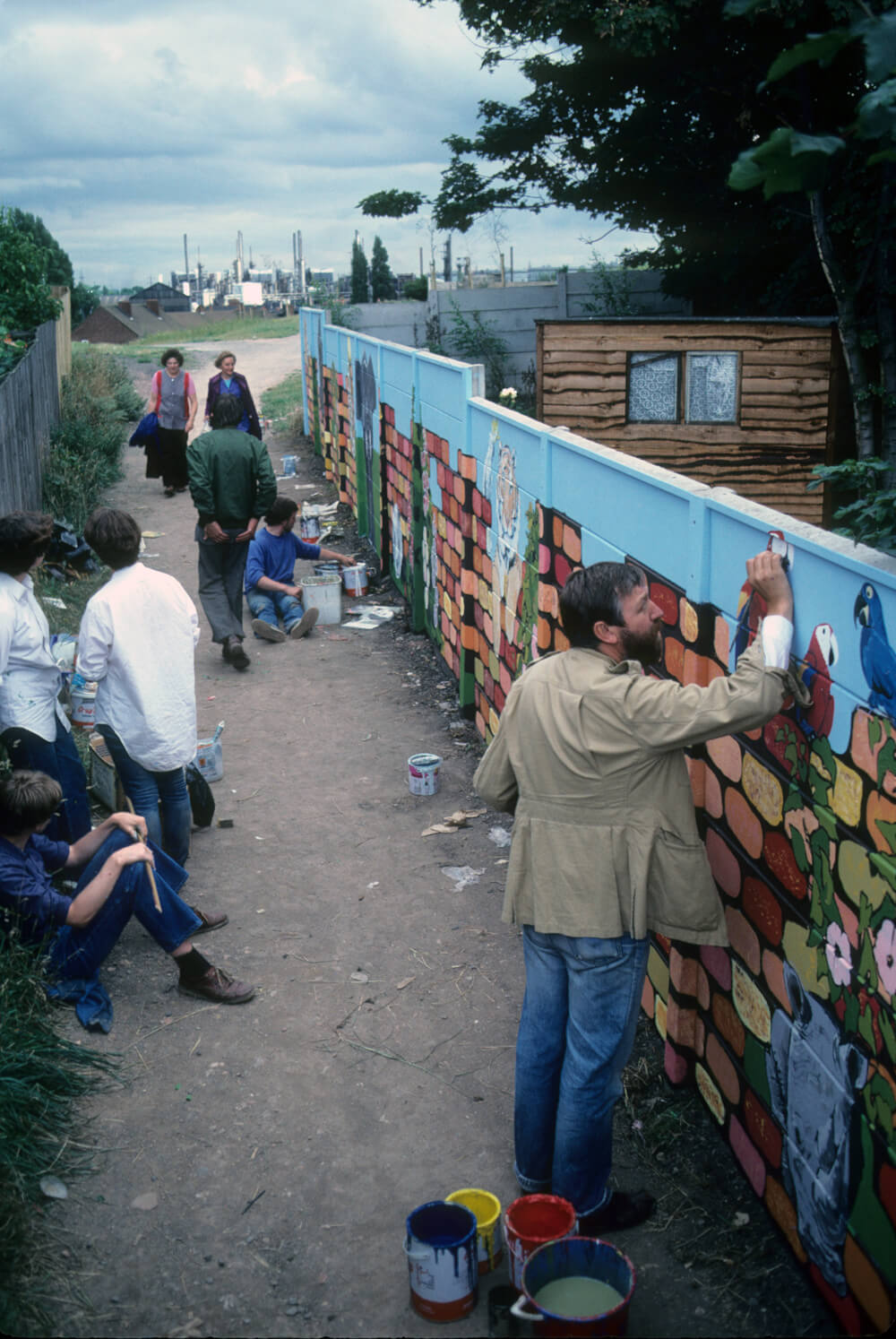

Derek Jones, pictured left, also came to work with Jubilee Arts in 1980 on a series of mural projects. He recalls: “At Oval Road in Tipton there was this dead concrete wall where kids would congregate and people didn’t like going down that alley, and they wanted to, for want of a better expression, ‘brighten it up’ and make it more ‘user friendly’, to change the whole atmosphere of this alleyway. It was 60 foot long.

Of course the Bus acted as a catalyst. Same with the van. The van would roll up and we’d have all these paints and people would want to get involved. ‘Can we help you, Mister?’ We thought of a way to get people involved without teaching them to paint. People can spend years trying to learn how to paint. We made this stencils, so we could mark it up in sections. The design was developed spontaneously rather than following a preconceived plan. All sorts of age groups were involved. They were painted with both acrylic and exterior emulsion. We did it in one block of time, following on from one of the play schemes. These things usually developed from contact made during those play schemes. The alley was on the way to the shops so we were never short of comments and suggestions from passer-bys.”

Derek did not see them of being a permanent feature. “At the time I thought well, it doesn’t matter if it lasts a year, but it lasted several. What really mattered was the moment people created that work, communication, the way people were talking to each other about it, the involvement of people, the camaradie produced by us being there with all these tubs of paint. All sorts of age groups were involved. It was hard work, but it was joyeous. We would take books and show them stuff, but we never tried to say this is how it should be done. We let it come from them, we didn’t try to impose an art style. I suppose there was a style though, using blocks of colour, which was easier than trying to put in al the subtle detail of rendering a piece of a material and tones. It had to have an impact, so we did use brighter colours. It was like an organic process, it grew as the communication and the way in which we worked together.”

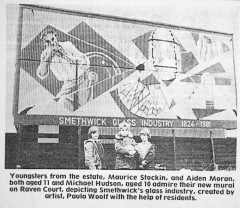

Sometimes the work Jubilee did was controversial, in that they were painting Black people and Asian people and they were prominent in the murals. Derek remembers some murals being graffitied. “One we did at Smethwick for a Community Action Project with artist Pam Skelton was immediately attacked, tubs of white paint were thrown over it. These things you had to deal with.” There was the case of an exhibition looking at the Afro-Caribeean migrant experience, called ‘Di Deh Yasso’, with an image of the face of a black woman on the side of the Bus, which was graffitied while at the bus garage.

Kate Organ recalls that mural project could have a downside. “There was an infamous story that went all around the country. On West Smethwick estate there was an arts project there with Community Links and Mark did a project from Jubilee with them to paint the gable ends of the maisonettes. There was the family who had got the mural at their gable end and their cousins came from Coventry to visit and said to them, ‘We can tell you’re deprived, you’ve got Muriels.’ That story more than ever galvanised those big questions about whether some of the interventions were about papering the cracks and prettifying something or were they purposeful interventions which change the power. These were the philosophical discussions of the time.”

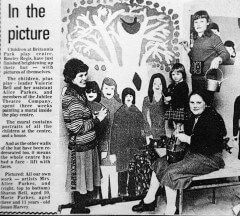

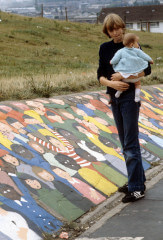

To alleviate this stereotyping, Jubilee also made floorals. This one, in Reservoir Road, Rowley, proved particularly popular. It was sited on a play area between several high rise blocks, the concrete flagstones providing a ready-made layout for a gigantic games board. The painting took place over just one week, with 20 kids involved. By the end of the week, the ‘Bus Gang’ had developed a whole range of games to play on the board. With the low walls at the edge of the play area also painted with goal posts and a football crowd, a basic kick about area was transformed.

As the Jubilee 1979-80 Annual Report says: ‘These murals show how play areas can be transformed from plain concrete to something magical. This has been achieved by children using colour, their imagination and enthusiasm.’

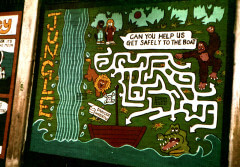

Super 8mm footage of the ‘Chinese Playground’ at Windmill Lane, Smethwick – the location for a play scheme to create a mural over two weeks.