The work on the Tantany estate harked back to earlier community arts methodologies and the idea of ‘area projects’. These were attempts to marshal the resources of a given geographic area – in Sandwell, there are six distinct towns and then several smaller districts with their own identities – using creative arts activities to bring together disparate groups to work on a common neighbourhood campaign or issue, to create a community forum, to think about the future of a local area for all the people who live there. Sometimes these become distinct entities, such as Sandwell Arts Council or Wednesbury Arts forum (who programmed events into the disused town hall).

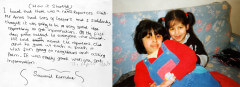

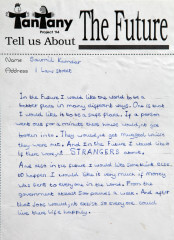

“Over six weeks we have taken the lead in talking to people and finding out their concerns about the area. We have interviewed people young and old – even our parents, taken photographs and planned a major community event to get more information. We hope that this display will make people look at the problems on Tantany and help us make it a better place. The project is the start of a larger venture involving Tantany people in looking at their community. Remember this is the start – there’s more that needs to be said…”

– introduction to the exhibition, 1991

It began with a request from Sharam Gill in 1991, who worked with Sandwell Racial Equality Council. There had been a problem on a road leading onto the estate from West Bromwich High Street. Young people were reported to be ‘hanging about under the expressway flyover, throwing stones at Asian women and an increase in racist abuse’. There had been a rise in violence particularly between black and white youths. There had been the usual round of questionnaires and extra policing promised, but what else could be done to engage with local youth? Beverley Harvey recalls: “There were suggestions about having a public event in a tent on a local playing field to bring youth together, but as I felt that there was significant evidence of segregation on the Estate not just across race but also age, then a youth-focused event would be more likely to aggravate tensions, and we needed to do something more. So Sharam worked with Jubilee to devise an outreach programme, which, in the style of early Jubilee, took to the streets, turning up with film cameras and interviewing people news style. This was an opportunity for young people to engage positively with both their peers and adults on the estate.”

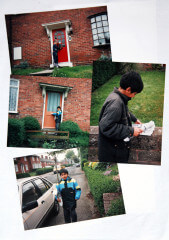

Before too long there was a group of teenagers voicing their opinion. There was some activity from the BNP locally, but a lot of the problems came from bored young people with nothing to do, with resentment towards authority figures. Over the summer, together the young people (between 15 and 20 participants) and Jubilee collected local opinions on the area – about the state of the environment, lack of facilities and leisure opportunities, and shared the results as a photo-text exhibition.

“The older people do not trust the young. It’s a shame because we could learn from one another. Some of the older people are really lonely and we’d like to get to know them better.”

– young person from Beaconsfield Street, 1991

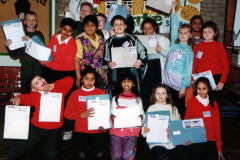

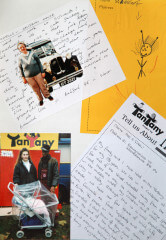

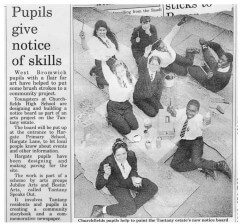

This was finally shown locally on a patch of open ground called The Jesson, where the group organised a festival event. During the day, they shared their findings with representatives of ‘the authorities’ whether these be school heads or police officers or town planners, as well as with local residents. During the evening they had a party, for the under 18s only, to celebrate. The participants had learned practical skills during the project – they were encouraged to take control of the process and deal with all the things you need to know about how to put on an event, from permissions to publicity, from public liability insurances to rainy day plans. As importantly, their opinions as young people living on the estate were given a prominence through the exhibition materials they had produced step by step, from taking the photographs, selecting texts from interviews they had undertaken, and producing promotional materials, from leaflets to newspaper press releases.

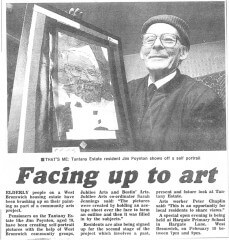

Alongside this, SREC set up Tantany Action Group to listen to the concerns voiced. This consisted of workers from different local authority departments – housing, planning, education and the youth service – alongside representative of local police, the British Trust for Conservation Volunteers. The event stimulated the discussions about how to strengthen community links. Following the event, members of the group put together a funding package to develop further work, which began in 1992. Jubilee were invited to coordinate a 12-month programme of activity, starting with an action research stage to focus on the views and main issues of residents, with a strong focus on young people leading the project. Alongside Jubilee, this work was undertaken with artists Peter Chaplin, Sam Hale and Karl, who were working together as Bostin’ Arts. Peter was a former member of Jubilee and Sam and Karl had worked with Jubilee on the Summer Celebrations programme in Sandwell and Dudley.

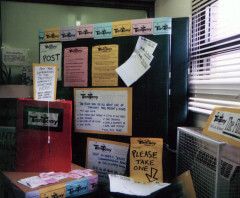

Installations with self-portrait booths were set up at different streets locations, as well as outside a newsagent, a shop, the post office. In return for a photograph, people were asked to return a comments form to collection boxes, which were left at these locations. BCTV offered the use of their van as a mobile collecting point, starting under the infamous flyover.

One comment: “Parts of the area look very attractive. The trees around the edge of the Jesson seem to be very well cared for and make the area look nice. There are some very scruffy places though, which have become overgrown. The graffiti is really bad too – some is sexist, some if racist, but most is just nasty and offensive.”

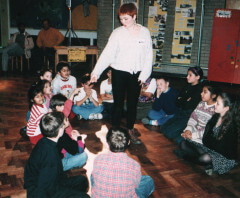

Young people helped organise an open evening in the autumn – an installation in a school hall at Hargate Junior, which brought together the collected materials and shared them with an audience of over 100 people. It was at this event that the idea arose to create a special newspaper and to create a handmade community storybook to tour local schools, pubs, elderly persons homes and schools – using the material as a starting point.

Stories were collected by a young group of ‘Roving Reporters’, who also later doubled as newspaper delivery boys and girls. Photographs and written material were also collected in the drop-off boxes situated in the local housing office and school. 2000 copies of the newspaper ‘Tantany Talk’ were delivered in a single freezing cold day to every house on the estate and surrounding areas. A community storybook, made up of five A3 folders was compiled and toured to local schools, libraries, pubs and the elderly persons home on the estate. Finally, a community noticeboard was designed by students from Churchfields school and installed outside Hargate Junior School, as a focal point for local news.

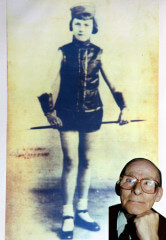

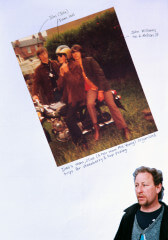

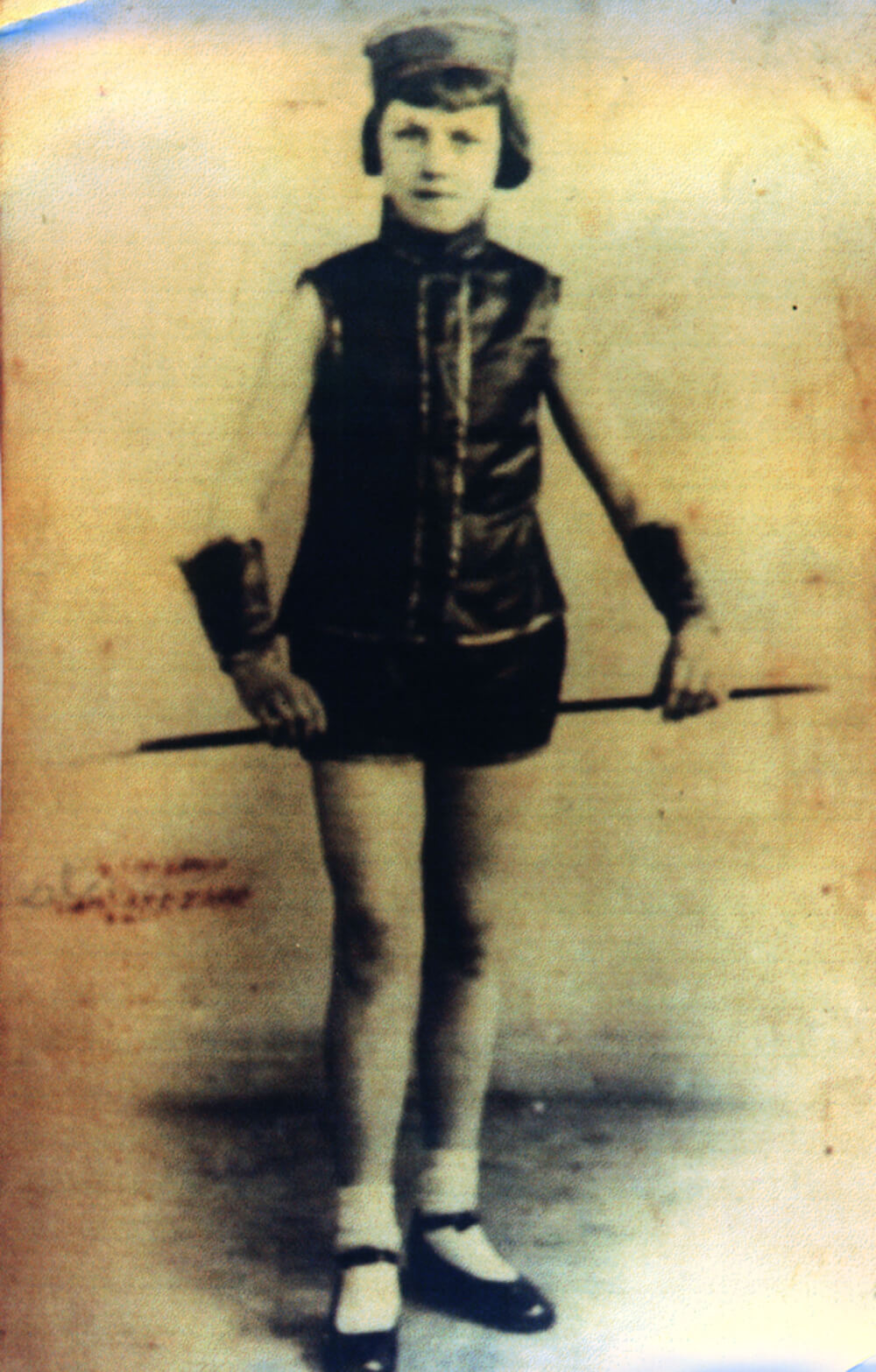

One of the most poignant stories was this one from Jim Poyton, aged 78, who lived at Salisbury House.

“This is my photograph of my very first sweet heart. We met at the Theatre Royal, West Bromwich, in 1933-34. These were some of my happiest days I was working at the theatre backstage operating the lighting, spotlights and switchboard. My wages at this time was eight shillings per week. From my vantage point at the side of the stage I watched my girl and other artists awaiting their cue to come on stage and she often looked up to me with a lovely little smile.

My girl together with her family associated together to rehearse plays and other musicals on a Sunday morning. I made myself generally useful such as helping the stage manager with his jobs, during the times of rehearsals.

The days of the theatre lived on for most of my younger days. To come back to romance with my girl, when my girl went home in the evening, I used to walk her home around nine’o’clock at night, and go back and carry on my job at the theatre till around 11 p.m at night. Often I was left to lock up the theatre after the performance. My mother used to come and see me at the stage door about twice a week and she used to bring me a 3d pork pie, then I used to go around to the box office and get her a complimentary pass for the front stalls.

Sadly, about September 1934, Phyllis, my girl collapsed and passed away on the stage during a performance. This caused the bottom of my world to fall a part and it took me years to console myself. So the final curtain came down on this part of my life.”

We used to have the flying arrow season. When the season started it was deadly, I got stuck in the back with one. There was that many kids up and down the street throwing them, real enemies. They was about 8 inches long and they’d go 80 mph, for about 200 yards you know. There was a knack to it. Tie a knot in a piece of string and fold it down like that; when you throwed it, put the ring on the finger, just like archery. Imagine that coming at you. From the moment you seen it, it was just whoosh!

The estate was hit by gas light and even the houses were lit by gas lamps. When electricity became available this was not installed free of charge but had to be paid for by the tenants – no money – no electricity. Eventually electricity was supplied to all houses rent was collected each week by a rent collector and one of these who vividly sticks in my mind and was a lady by the name of Miss Philips. She kept the residents in line and looked up on the estate as her Garden of Eden and she intended to keep it that way by telling residents to put right what she considered wrong. In our days there was no such thing as a plastic sledge. See, on the Jesson it had a steep slope, 80 foot to 100 foot high and the top of it was flat. It used to take your breath away running up it. When it snowed, that’s when it really sorted the men out from the boys. Well, the girls went first, such as my sister.

We used to go to the shop and ask if they’d got any old biscuits tins, the lids were square and you had a little lip all the way round that you could hold on to. When you pushed ’em they went sliding down. I remember me sister, our Sue, went first. She came back white with her hair standing up, she was sick and said “Never again.”

I remember just before I got 18, we found out about plastic fertiliser bags and we went down on them. I mean 18 years old, coming out of the pub, acting soft, 3 or 4 on a plastic bag all over the bumps. You could sit inside them and you didn’t feel the bumps until after.

– from interviews for Tantany Talk, 1994

We’d spend our money down the chip shop, Bellingham’s fish shop in Hargate Lane, especially on a winter’s night when it went dark at 4 or 5 o’clock. Soon as they opened we’d have all the batter bits from dinner time, 2 pence, and her’d fill it up that big. I mean if it weren’t for her lots of kids would have starved, meaning myself. I mean 4 pence worth of batters, you wouldn’t carry ’em out of the shop. That was food. People wouldn’t eat that today, they’d be sick. I’d still eat it, it done me alright. Everything that was pumped into you was all rendered fat. Kids in the street used to take fried bread, basically soaked in beef and dripping to school with brown sauce on it, ’cause we were the unfortunate ones.

– from interviews for Tantany Talks