Over three summers, Jubilee worked in collaboration with the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw and an informal group of arts educators in Poland, on a series of residencies to share community arts practice, to go beyond the walls of the gallery and engage with local people.

These were organised in co-operation with Janusz Byszewski, co-founder of the artist group Partner (1983 – 1990) and since 1989, curator and founder of the newly established Creative Education Laboratory at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw. Janusz had undertaken a series of mail-art exchanges with artists across Europe in preceding years and literally turned up on Jubilee’s doorstep, at their centre in Greets Green, in the summer of 1989. He had been visiting a group called Artlink in the West Midlands, who specifically worked with people with disabilities and in turn they sent him to Jubilee.

The creative workshops took place in Reymontowka, the former residence of writer and Nobel Prize winner Władysław Stanisław Reymont (1867-1925). Now officially known as Rest House for Scientists and Artists at Chlewiska, Kotuń Commune’, this residential centre centre is placed among forests and meadows near the village of Pieróg, about 30 kilometres from the border with Belarus. Each summer they hosted a series of artist residencies.

The nearest largest town was Siedlce, which has a rail link with Warsaw and Moscow. Around 40 families inhabited the village. The landscape in this part of Poland is flat plains – a combination of agriculture and extensive deciduous forest. Most families farm, and for many this is the sole source of income. There was no mains water supply; everyone had a well and the main form of transport was still a horse and cart.

The participants were artists, cultural anthropologists and cultural co-ordinators, who had mostly been employed in cultural centres (local Dom Kultura – Houses of Culture) organising arts education activities as local Dom Kultura – Houses of Culture. Under Communism, every village and town had it’s own House of Culture, part of the state, but with the former institutions of the state being dismantled along with the funding. Some of the questions facing these artists was ‘How do you operate as community based artists in a free market economy? How do make culture a vital force on local life? How do you ensure the commitment from local government?’

The workshops offered the opportunity to extend skills and ideas in contact with other artists, The first workshops were led by Lee Corner from ArtLink and Sylvia King from Jubilee. She recalls:

“I remember making art works out of loaves of stale bread

I remember walking round the house looking at pebbles and tree and the pond as a performance piece

I remember the twins dancing ethereally in the dusk

I remember walking through fields of spring flowers watching horses pull ploughs and being immersed in the beauty and intensity of the land

I remember the first gathering and hearing names of countries I didn’t know existed – Estonia, Lithuania

I remember passionate conversations about racism with Eastern Europeans

I remember dividing into groups based on carving up Europe: the northern Europeans; southern Europeans, western Europeans, eastern Europeans

I remember the feeling of walking into the dining room at lunchtime – sharing food and endless conversation

I remember Byszewski – ‘To skomplikowane – it’s complicated’… everything is complicated”

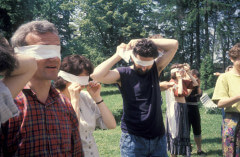

In the second edition Jubilee challenged the participants to undertake a range of artistic activities and engage with local residents in the village around their issues and concerns. These included using percussion, vocal and theatre activities, photography, video and puppet making. At first the artists were nervous, expressing scepticism that anyone would get involved. After forty years of communism, people did not find it easy to speak openly, so they preceded with some caution. The village had no street signs, and one of the activities that did get people talking was the naming of place. The group devised was ‘a ceremony of signing’ – the outcome of the project was to agree the location of the centre of the village.

“It’s difficult in the country for children. They are often forced to work. The arrival of the artists gave them some respite. There was entertainment. We didn’t usually have time for that. When they left, we thanked them for that. And they thanked us. But why should they thank us? ”

– Krystyna Kokoszka

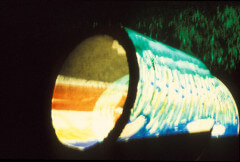

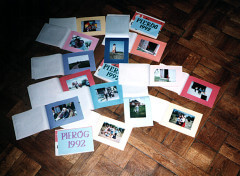

It was very difficult to find the centre of the village as everyone had a different view. In the end there was an agreement over a certain spot and a festival was designed to celebrate the findings. Participants wore robes and clay masks and processed through the village with percussion instruments. Villagers were invited to view all of the other performances that had been prepared. However, there was an entry fee: you had to make a drawing on a slide transparency, which was then projected onto barns and houses around the village. One villager was so excited he brought his horse so that his slide could be projected on it whist riding. The children performed their hopes and dreams with a shadow puppet play performed behind a sheet tied between two trees and the moon light acting as a source of light. At the end of the residency, we are pleased to note that, in their honour, two Jubilee members, Tony Stanley and Beverley Harvey, were nominated as King of Pieróg and Forest Maiden.

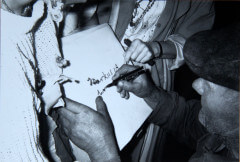

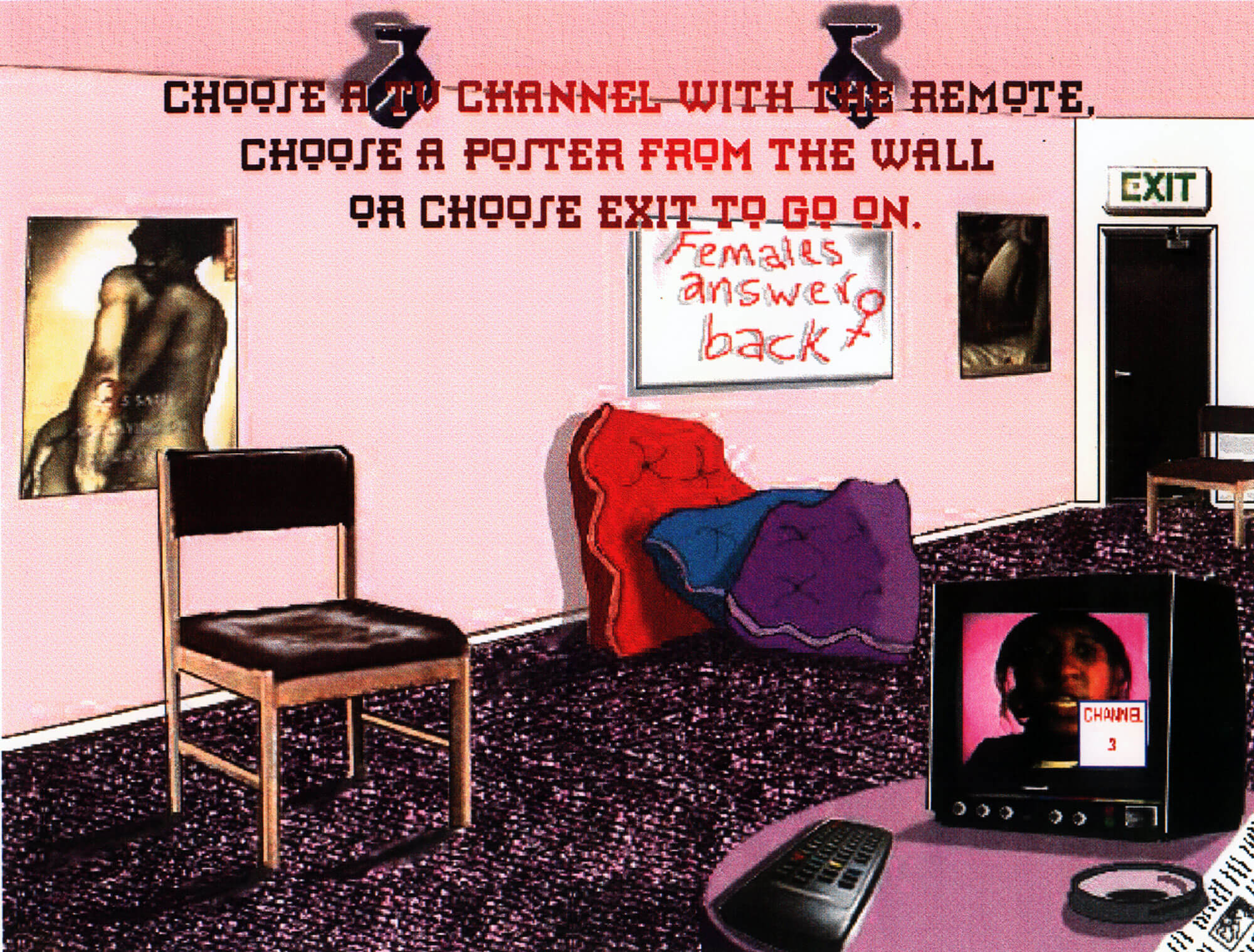

In the third edition, the theme of ‘Home’ was explored, attempting a deeper engagement with the villagers. The artists worked with villagers on the theme, creating portraits and self-portraits. Joining the team from the West Midlands was Dave Rogers from Banner Theatre, with great experience of actuality recordings – using these as the basis for writing and performing songs – and photographer Sue Green. Together they created an exhibition, slide shows, music and drama presentations, using a building which usually housed the village engine engine.

Over the three summers, Jubilee played a key role in sharing community arts practice especially with a view to engaging the villagers. Discussions around invasion of privacy was a very topical discussion; for example, at that time, cameras were very much associated with the mechanisms of state surveillance and the idea of people talking freely about their hopes and aspirations (and sharing them) was a novel experience, even for the artists. The idea of making ‘statement posters’ with young people and then decorating the abandoned village hall to create an exhibition and meeting space led to some incredulous looks at first. Many of the villagers asked if the artists were really Jehovah Witnesses as they were the only outside people that visited and enquired about their lives.

However, in the end what surfaced was the power of curiosity amongst the villagers. Still, Jubilee was challenged on this project: they did not speak the language and their technological equipment had no particular advantage, hence resorting to traditional methods, creating shadow plays by moonlight.

Many of the participants of the workshops went onto work with significant arts institutions and universities, which later led to longer-term collaborations and creative relationships, which stand to this day.

An article from 2021 by Weronika Plińska (in Polish) describes in detail the philosophy behind the work. See: magazynszum.pl/wydarzenie-artystyczne-i-jego-slad-projekt-4-x-pierog-1990-1993-laboratorium-edukacji-tworczej-csw-i-jubilee-arts/

Comments from participants

Pierog is nothing special, which is why no one would come here. Chlewisk is another matter. Everyone would go there. They have fine buildings, green houses, asphalt roads right up to your front gate. Our roads are just sandy. Then all of a sudden, banners, bells, people dressing up, the village was decorated. There were signposts everywhere and posters being made! My Sylwek and my Kasia had to attend rehearsals every day. Sylwek chatted away at the microphone – he had a part to play! They left masks for some of the children. It was festive occasion. They even helped a widower to gather in the hay. He was so pleased and surprised!

– Mrs. Kaczorel, the Village Administrators Wife

This type of workshop is always extremely difficult because all those taking part measure themselves against their weaknesses; having to do impossible things, insurmountable difficulties, questions for which there are invariably no clear or unequivocal answers. However, this is exactly where the value lies in such meetings. What fascinated me more than anything else was the unusual accumulation of catastrophes throughout the course of out meeting: the tree, which in some sense was a symbol of these workshops, was toppled during a storm; the hailstorms of extraordinary magnitude; the death of the oldest person in the village, a fire, a road accident, all of this takes me back to that time.

– Tomasz Teodorczyk

Strange but True

The project was supported by the British Know How Fund, a programme of the British government that assisted former Soviet-bloc nations in the transition to the free market. In support of Poland’s early political and economic reforms after the fall of Communism, Polish groups could apply to this fund for technical assistance to be provided by British experts in enterprise. Through the Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw, Jubilee were thus invited to a seminar in London – which was attended primarily by banks, captains of industry, tax and finance consultants. The only other arts organisations there were the R.S.C and E.N.O – we have no idea if they did any projects through this fund. Some years later, we were told that Poles often referred to this as ‘The Know-It-All-Fund’ and consultants as ‘The Marriott Brigade’.

Janusz Byszewski works with the Creative Education Laboratory at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw; since 1996, conducts workshops in creative situations of specialization Culture Animation Institute of Polish Culture. Author of several projects in Poland and abroad. Books: ‘Here I am’ (1994), ‘Other museum’ (1996); M. Parczewską co-author of ‘Creative Situations’ (2005), ‘Home, my centre of the world’ (2005), ‘Contemporary Art – Manual’ (2007/2009), ‘The Museum as a social sculpture’ (2012), ‘Museum on the Move’(2013).