Phone rings. ‘Hello, is that Jubilee Community Arts? This is Churchfields School, just down the road in Church Vale, overlooking Sandwell Valley, yes. We’ve just been designated Sandwell’s first community school. We’d like to talk to you about what that means.’

Churchfields was one of the country’s first comprehensive schools to open, in 1956 – and certainly the first in the West Midlands. Jubilee were invited to run a residential training weekend at Ingestre Hall (the borough’s residential centre in countryside near Stafford) for 20 staff from Churchfields, to explore concepts of community engagement using a range of media. Following this, Jubilee ran a further series of introductory sessions to community arts practice with staff from the English and Art Departments to consider how to make new connections with the local community. Jubilee first helped them document ‘a day in the life of the school’, photographs used extensively to present the school to the community through a travelling exhibition and events. The group then devised a project, deciding to focus on the memories and experiences of being 14 years old, growing up in West Bromwich and thereabouts from the early 1900’s to the present day. The project resulted in the publication of a 76 page book, which was distributed locally and launched at the booksellers W.H Smith on West Bromwich High Street.

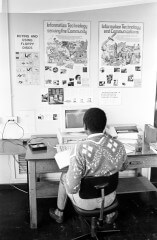

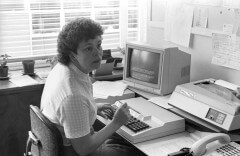

“The book was edited in a day with a group of 30 participants, an early example of the application of new technology – in this case, eight Mac SE’s for word processing and desktop publishing programmes. The book was simply laid out in an early version of Adobe Pagemaker and the illustrations were scanned in using a hand scanner.”

– writer Kath West, one of the project workers

The title of the project was taken from a comment of one of the teachers: ‘Oral history is about memory, and our memories bend the truth a little bit, don’t they?’

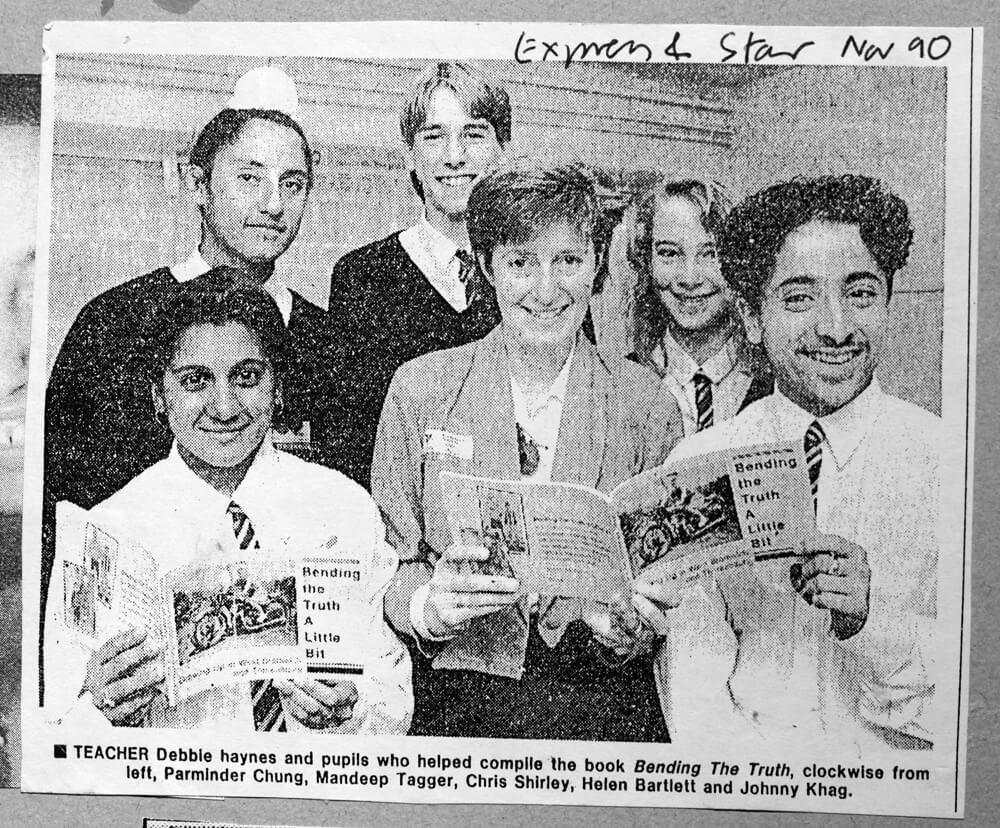

The process was described by Debbie Haynes, one of the teachers involved with the project: “This oral history book is the culmination of a year long project which aimed to strengthen the links between a community school and the people living in the surrounding area. The school is situated just outside the centre of West Bromwich, in the heart of the Black Country conurbation.

The project was unusual because it included contributions from many different social groups. Young and old, people who have lived all their lives in the West Bromwich area, people who were born in other parts of the world but have come to live and work in the area, and people who work here but live elsewhere.

A more diverse group of people could not be found and yet they all have something in common. They are, or once were, 14 years old. This particular age was chosen to be the focus of the project. The conclusion reached about this age by the present 14 year olds is that it is not a special age, it is almost a ‘nothing age’, when you are too old for childish games but not old enough to engage in those activities which are regarded as adult.

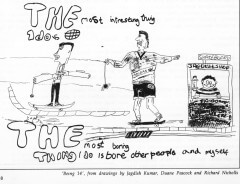

And yet it used not to be like that. If you ask one of the sixty or seventy year olds what they were doing at 14, they will tell you that they were just leaving school to go into work, it was their coming of age, to go to one of the local engineering factories or into service in the larger homes of wealthy people. The stories and experiences in this book were collected through interviews with local people by a group of school children at Churchfields and a number of community artists. Usually an oral history project of this nature relies on interviews which are tape-recorded, but this was not entirely the case with ‘Bending The Truth A Little Bit.’ We also used a method which involved asking questions, taking down key words in note form, then writing up the essence of what was said into a story. It was surprising how much could be remembered and then retold almost in the same voice of the original.

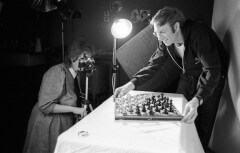

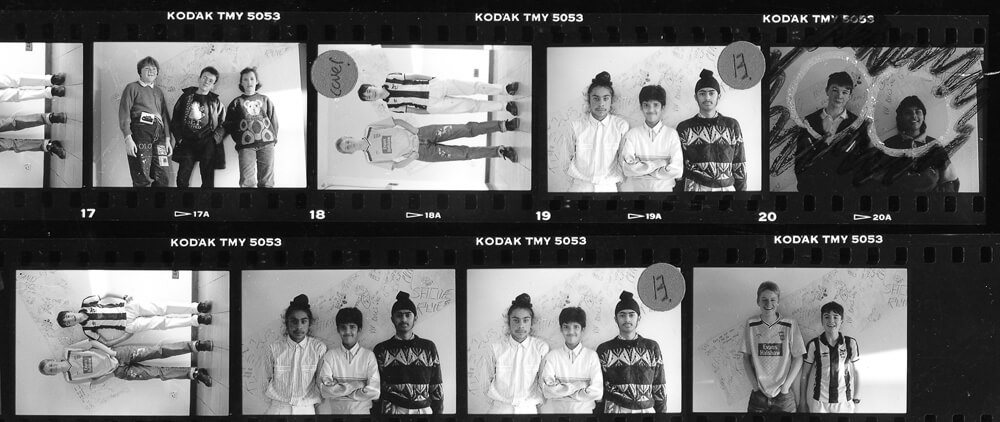

We set up the project with Jubilee and the search for stories began with Kath West, a local writer and Sue Green, a photographer, who arrived to meet a class of third years. They encouraged them, with their History and English teachers, to write about the age of 14 by interviewing each other. “What’s it like, what do you do?” Sue concentrated on a series of photographs which would allow the class to represent themselves through their choice of clothes and possessions.”

“I used to put some of my pocket money towards buying singles with my older sister. They were six shillings and eight pence then – and we’d put half each. I used to get ten shillings a week pocket money (or 50 pence now). We bought records by The Rolling Stones, The Monkeys (my favourite). My sister liked Dusty Springfield best. We had a portable record player and when our parents were out we would play our records and practice our dancing.”

“All the kids were into Elvis Presley but I was into Tommy Steele. I went to see him at the Hippodrome wit ha friend and we had a box. We waited outside and got his autograph. It wasn’t like the hysteria nowadays. There were only a few people there, about a dozen. I had his picture on the wall above my bed and one night my older brother came in and told me that Tommy Steele was going to get married – so I wouldn’t be able to marry him. I was dreadfully upset at the time but the crush only lasted a couple of years until I got interested in boys.”

– from the publication

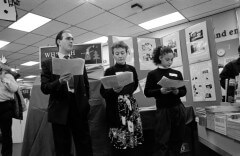

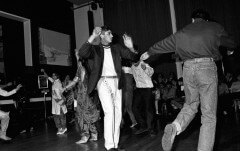

From the material that was collected they organised a display – another good opportunity to collect more stories. Other artists from Jubilee planned an activity day where an exhibition of photographs and artefacts, past and present, would be displayed with the stories that the people had told. The day was widely publicised and people who came to the exhibition were also interviewed by third years, who acted as scribes and stories were also taped in a recording booth. The event has exhibition material such as a ‘floral’, when album covers from the past thirty years were laid out to create a huge visual mosaic on the floor of the school hall, along with a dansette record player with a stack of 7-inch singles. The young people of the day were fascinated by this ‘old technology’, being more used to listening to music on C-90 cassette Walkmans. The students also presented readings of the stories collected. This day was enjoyable and successful as many of the individuals who had been interviewed previously now had the chance to meet each other.

By now a substantial amount of stories had been collected and transferred onto computer disc. The time had come to read and edit the material. Another special day was arranged when a group of pupils, teachers, local people and project workers could go through all the stories, make a selection, and organise chapters. Was it possible to make a book in a day? (This idea came about when Jubilee invited down Brian Lewis from Yorkshire Arts Circus, to share his experiences of community publishing with us.)

Debbie Haynes: “It was a hard day’s work. The stories were at last collected together in one place. The book, which had been planned and aimed for, looked almost ready. But not quite! The photographs had to be chosen and the book carefully laid out page by page to create the ‘camera ready artwork’ to take to the printers. This was done with the help of Beverley Harvey and Brendan Jackson from Jubilee, again with the involvement of some third years, by utilising computers with desktop publishing facilities.”

One of the project workers in the final stages of editing the book said that she almost knew the stories off by heart, she had read through them so many times even to knowing who had had said what just by looking at the text. But, she said next, she looked forward to coming back to work on the book; to engage with the language and experience of these local people. In spite of the diversity of experience that each story teller has contributed, the stories speak of similar themes – of family and school, work and leisure. This is why the chapters of the book were arranged in this way.

Debbie Haynes: “Certain editorial decisions were made about the organisation of the stories. The names of the contributors have not been attached to the stories they told but appear at the front of this book. When a different speaker begins their story this was indicated by using a graphic symbol at the beginning of the paragraph. Where the speaker has used dialect we tried to preserve this is in the spelling. All this was been done in the hope that a unity of experience will be communicated through the original speech of individual voices”

Extracts from ‘Bending the Truth’

When you are twelve or thirteen, 14 may seem the age when you grow up and begin to be treated as an adult by other adults. In reality, when you wake up on your 14th birthday, you begin to think that 14 isn’t any different from when you were thirteen – after all you are only a day older.

I think children today have a lot more freedom, but I think they have a lot more problems because they have the freedom. Things were far more black and white for us; there weren’t so many grey areas. Today, they have to make more decisions for themselves. I don’t think I’d like to be 14 now.

This is the year that almost too many responsibilities are put on your shoulders: this is the beginning of the rest of your life.

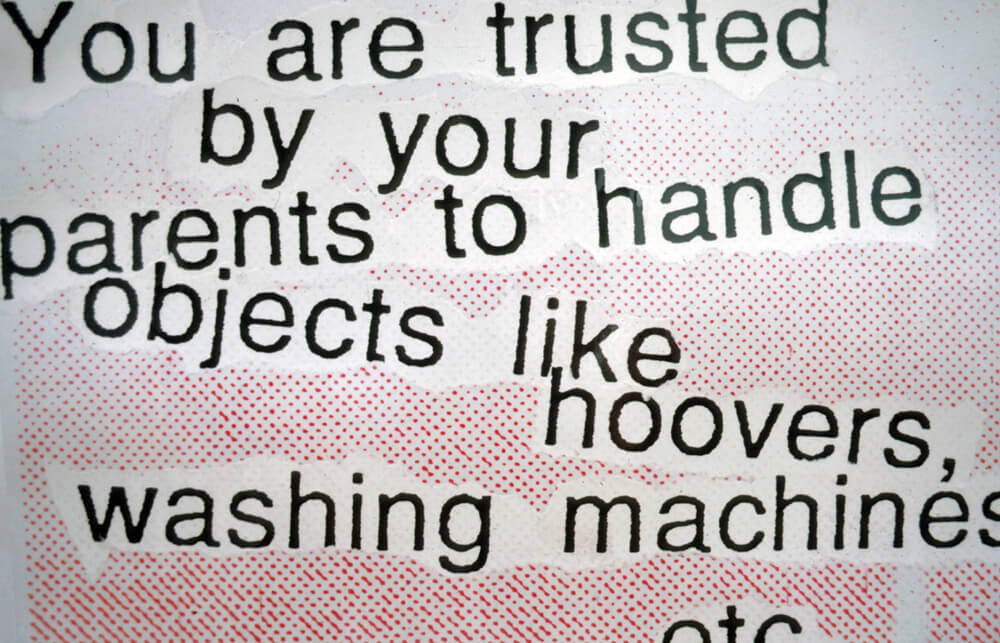

You are trusted by your parents to handle expensive objects like hoovers washing machines and so on. You are also trusted more to look after your brother and sister when your parents are out. When I was 13 we had to go to our auntie’s, but now my parents say I am old enough to stay in the house on my own. Then you ask for spending money in return.

I always wanted to have hair like Cilla Black. She looked great on ‘Top of the Pops.’

I used to have my hair cut three times a month at the barbers, and the barber used to say to customers, “Anything else, Sir?” I didn’t know what he meant; I thought he meant combs and things like that. Then he would say to them, “Would you like some durex?” The thought of buying something like that frightened me. I felt really embarrassed. There was a lot of taboo in those days.

At 14 you learn to mix with other people; you begin to understand them as they really are and you start realising the problems other people have.

14 is not a special age.

Compared to us, the children of today live in Paradise.

14 is an age when you start growing mentally and physically. For example you start getting spots. This is the thing that probably worries most 14 year olds.

Parents start to give you lectures more often when you’re 14. They say you should act like a 14 year old – not that we don’t! They give you never-ending lectures which begin: “When I was your age…” You can get really sick of it.

At 14 I think your political feeling begin to reveal themselves. Not so much ‘political feelings’ as thoughts about what the world is doing here and who says everything has to be governed by time. I often wish I could get out and do what I want to do not what other people say I have to do.

Some Facts on 14

The young people working on the project uncovered the following information during the project. We’d like to share it with you…

Compulsory schooling is from the age of 5. A typical school at the beginning of the 20th century had pupils from 5 and under until the statutory leaving age of 12. At this age children were permitted to work half-time and often left school. The statutory age was raised to 14 in 1921, to 15 in 1947 and to 16 in 1972-73.

At the beginning of the 20th century, a young person was likely to suffer from one or more of the following: tuberculosis, typhoid, influenza, pneumonia, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, and measles.

The Children & Young Persons Act (UK) of 1933 defined a ‘child’ as a person under the age of 14, and a ‘young person’ as someone who was at least 14 but less than 17 years of age.

By the time Tutankhamen, Egyptian ruler of the 18th Dynasty, had reached the age of 14, he had ruled for nearly four years. He had been married for as long!

By the age of 14, Judy Garland was contracted to M.G.M – who provided her with schooling, dancing and singing lessons, sent her to exercise classes and put her on a diet. She was also given diet pills, unaware of the dangers of amphetamine addiction.

Marilyn Monroe was in a foster home at the age of 14.

In several states of America, a girl can get married at the age of 14 – depending on parental consent.

At the age of 14, Amedeo Modigliani began to take drawing lessons. At this age he also contracted a nearly fatal dose of typhoid fever.

At the age of 14, Rolling Stone Keith Richards was ‘asked to leave’ Dartford Technical School for alleged truancy.

In 1818, a bill was passed by the House of Commons limiting work for children to 11 hours a day, but was overturned by the House of Lords. The Lords set up a committee which reported that factory labour was, in fact very healthy for children.

In the the 1830’s pit children began to work below ground before they were seven, doing 12 hours a day. Girls were employed to drag the coal, work later done by pit ponies.

Edgar Allan Poe began to write poetry at the age of 14.

At the time of her ill-starred romance with Romeo, Shakespeare’s Juliet Capulet was only 14 years old.

Mozart had written several operas by the time he was 14.

An Act of Parliament in 1833 laid down that children under 9 could not be employed at all, those between 9 and 13 could only work 48 hours a week and those between 13 and 19 could work 60 hours a week.

In 1875, a 14 year old boy was sent up a chimney at a lunatic asylum near Cambridge and swallowed so much soot that he died. The master sweep was sent to prison for six months for negligence. This event caused a public outcry and helped a bill through Parliament, which enforced legislation against using children in this kind of work.

Elvis Presley had been playing guitar for two years by the time he was 14. His Dad had bought him a guitar because he couldn’t afford what Elvis really wanted – a bicycle.

Michael Jackson tells in his autobiography ‘Moonwalk’ how he worried about a dreadful outbreak of spots at the age of 14.

According to a 1989 Gallup Opinion Poll, the greatest concerns of young people (aged 16-24) were AIDs, drugs and pollution of the environment. Violence on television was the least concern.

Our own local opinion poll with a sample of fifty local young people aged 14 from Churchfields came up with exactly the same results. In our opinion poll, we also asked 14 year olds what was of most interest to them. Top of the list (with 50%) came their Family, followed closely by Sport and Pop Music. Interest in Politics was low, and 60% put the Arts at the very bottom of their list. Over 60% put Sport as their main hobby. Less than 5% were interested in computers as a hobby, but listening to or playing music also scored highly, along with reading. Other hobbies that were mentioned included ‘collecting key rings’, ‘watching evening surgery at the vets’ and ‘annoying my brother’…

Churchfield School was closed in 2001, and all the buildings demolished. The site was later developed as a new residential complex, overlooking Sandwell Valley. There is a Facebook group by Sandra Meredith which charts the history of the school.