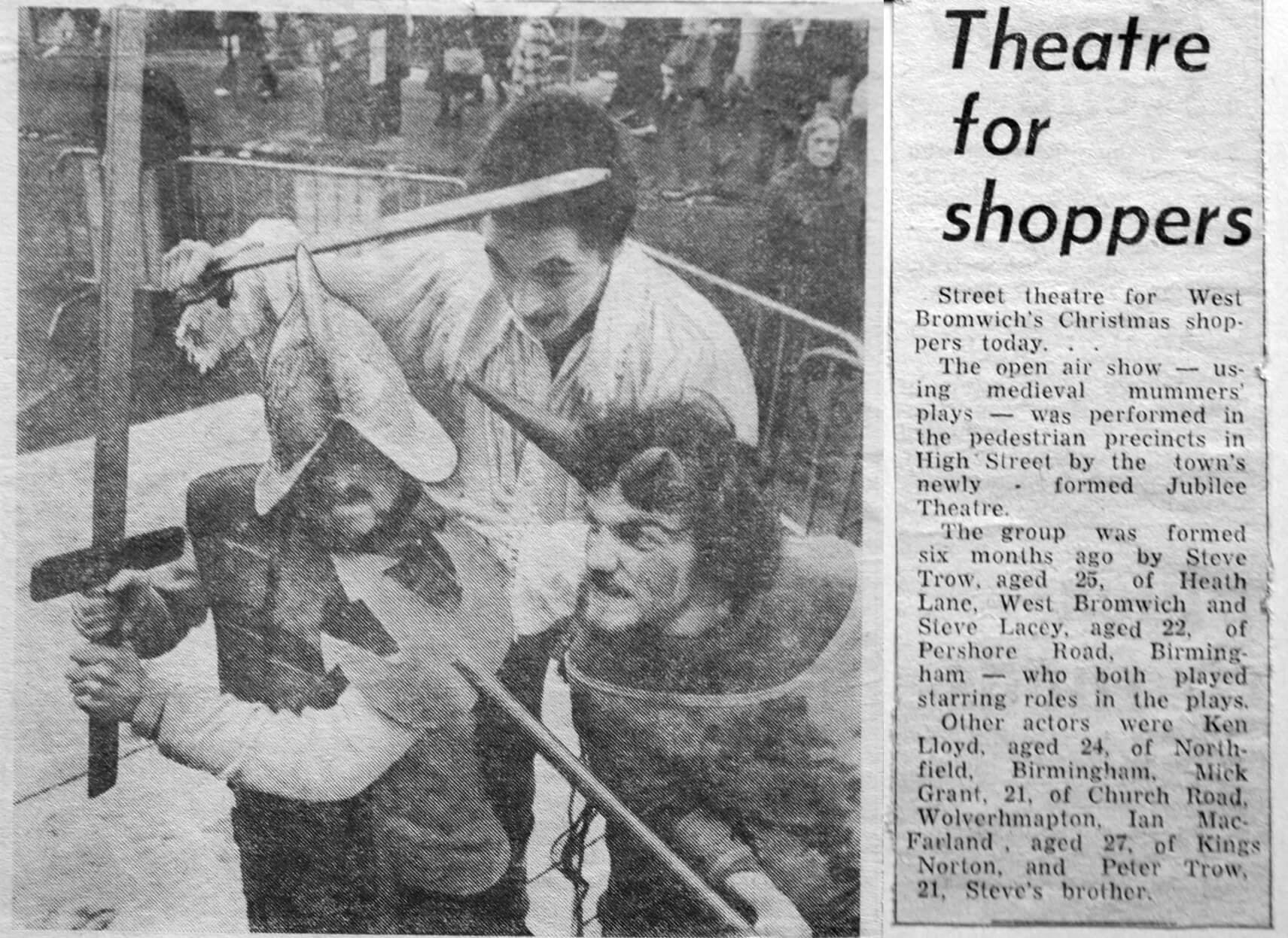

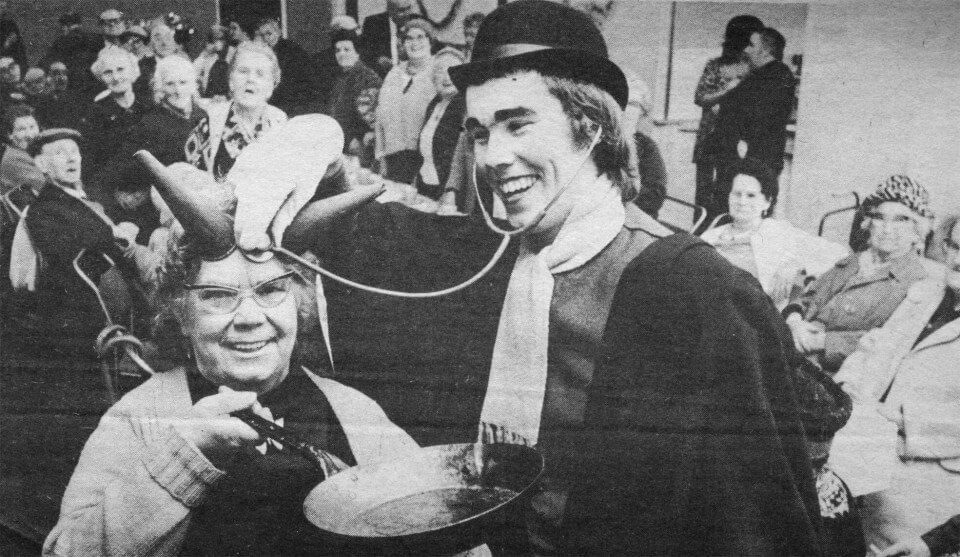

In 1974 the first hand held pocket calculators appeared in shops, New Year’s Day was celebrated as a public holiday for the first time and Pink Floyd released ‘Dark Side of the Moon’. At the cinema you could see ‘The Exorcist’ or ‘Blazing Saddles’. There was Three Day week and two general elections. As part of local government reorganisation Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council was invented, and a group of theatre students founded Jubilee Arts in West Bromwich.

Their first official outing was an appearance on the High Street in December of that year, performing a Mummer’s Play outside of Woolworths.

Both ‘Wassailing’ and ‘Mumming’ were not uncommon in parts of the Black Country, with performers calling themselves ‘guisers’, blackening or flouring their faces as participants were intended to remain incognito. On Twelfth Night, wassailers went from door to door (or public house to public house in many cases) singing and drinking – a tradition which came from agricultural workers, who visited orchards with incantations to ask the spirits into ensure a good harvest the following season. The word ‘wassail’ comes from the Anglo-Saxon phrase ‘waes hael’, which means ‘good health’. The custom of carol singing is a descendent of this.

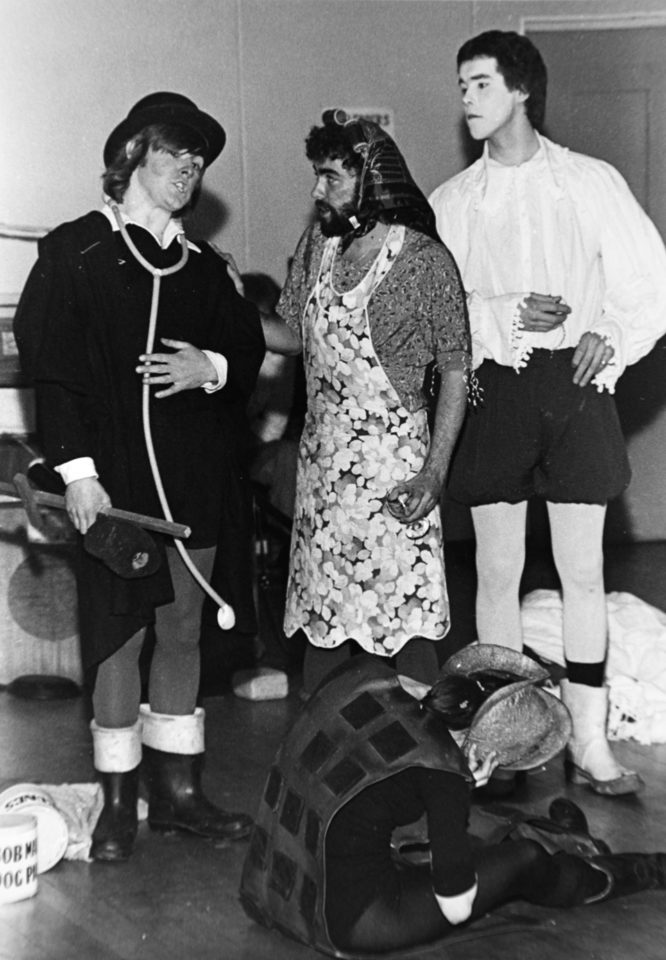

Mumming is also an ancient custom, performed by a troupe of actors at Christmas and Easter. It means ‘making diversion in disguise’. One of founders of Jubilee Theatre, Steve Trow, was intrigued by an article he had read about the Gregory family of Wednesbury, who had performed an annual Christmas charade some 60 years earlier using Mummers characters. Inspired by this, he wrote a script in Black Country dialect with fellow student Ken Lloyd. Steve recalls:

“The high street had been pedestrianised, a least the part outside of Woolworths. We had a workman’s tin hut on the pavement and we were all crammed inside the tin hut, and it was windowless, so we couldn’t see out at all. The format of a mummers play is a series of entrances and interactions and all the characters emerge one at a time. We were esconced in this tin hut sp we couldn’t see how it was going down.

The first person to come out is Father Xmas, Santa Claus, and says ‘How do, how do, Ah’m Father Xmas, there’s no doubt yow’ve guessed’… because of his costume. The cast was me and people from the University, and my brother Pete, who played the part of Slasher’s mother, and he wore a hair net with rollers and he had a beard. We ended up with an audience of about 50 people in West Bromwich.

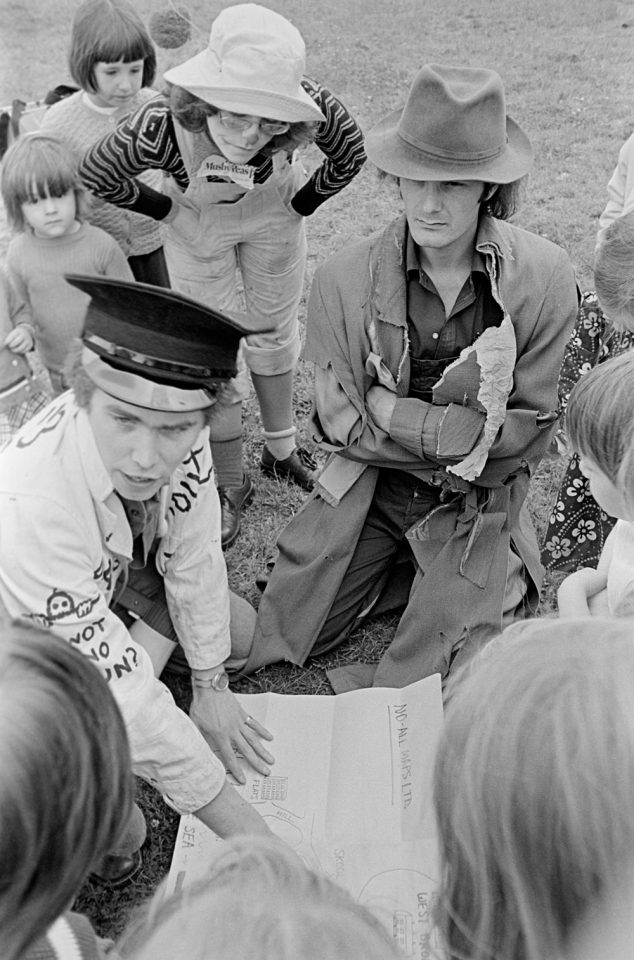

Then we did it in Wednesbury, in the Shambles, when the market was still there. The mistake we made was that we were across the road from the market stalls, about 50 yards back, expecting the same kind of audience as West Bromwich. So when Father Xmas went out he cracked up. He started well enough and says, ‘How do, how do, Ah’m Father Xmas, as no doubt yow’ve guessed..’ It’s all in rhyming couplets, even the asides, and then he says, ‘On afore we start can yow all move back and mek some room, cos they cor see and we’m starting soon.’ At that point he cracks up. We’re inside the tin hut and we can’t see what’s going on.

We’re thinking, ‘Get a grip, get a grip, this isn’t time to corpse.’ The next entrance is Saint George, so he has go out and pull it together. He says. ‘How do, I’m Saint George and ah’m the best, with me helmet, sword and six foot chest.’ Then he cracks up as well. Everyone that goes out cracks up. We didn’t realise until we went out there was nobody there. There was no audience. There were just three people and a dog on the other side of the road, about two stalls down the row, craning their necks and wondering what the hell is going on. But in West Brom it went down a bomb.”

This was the beginning of the work of Jubilee, making work rooted in locality, using shared or communal memories, playing with traditions and their landscapes and location And having a laugh. (That would be ‘loff’ in local dialect.)