The photograph here was taken on a bitter cold morning in February at the Public Works Depot, a site at the bottom of Sandwell Road where it was dead-ended by the Expressway, which itself looped around the town centre from Junction 1 of the M5 to Carters Green. Here we see a local councilor, John Edwards, standing on a podium to address the workers who are occupying the Depot during a dispute with management over the sacking of their shop steward George Hickman. At that time, the borough had by far the highest percentage of council tenants in the region – 514 per 1,000 – giving the Public Works Department a significant role in repairs and maintenance of council assets.

John Edwards served as a Sandwell Labour councillor for 43 years, representing the Greets Green and Lyng ward, where Jubilee Arts had their first base. He was the Chair of West Midlands Fire & Rescue Authority, and served as Mayor in 1999-2000. Prior to that he had been a firefighter for over a decade, until a knee injury forced him to quit. He then studied politics as a full-time student, opened a bookshop as a non-profit cooperative and stood for election. He also became a board member of Jubilee Arts for several years. His Twitter profile reads: ‘…always a Socialist, allergic to bigots.’ The megaphone he is using in the photograph may or may not have come from the cupboard at Jubilee.

In 1965, Jennie Lee presented her White Paper for the Arts, the first one and the only one for the next half-century. She had been appointed Arts Minister in Harold Wilson’s government, where she was also key to the development of the Open University. Her premise was that the state had a moral duty to support artists and the arts, and that they should be made available to the many, not the few. She stated: ‘In any civilised community the arts and associated amenities, serious or comic, light or demanding, must occupy a central place. Their enjoyment should not be regarded as remote from everyday life.’ She was responsible for expanding work in the regions, as well as establishing new institutions such as the South Bank Centre, and trebling the funding for the Arts Council over the next six years.

When the Arts Council was first established in 1946, the first chairperson, the economist John Maynard Keynes – mindful of the use of art for propaganda from the politicians in power, so recently in Nazi Germany – formulated the ‘arms length principle’ for funding, allowing for artistic freedom, independence and non-instrumentality. In recent years, this has been called into question. Culture Minister Oliver Dowden (2020-21) argued: ‘As publicly funded bodies, you should not be taking actions motivated by activism or politics… The significant support that you receive from the taxpayer is an acknowledgement of the important cultural role you play for the entire country. It is imperative that you continue to act impartially, in line with your publicly funded status, and not in a way that brings this into question.’ The context of his comments was a response to the removal or relocation of controversial statues by local authorities and museums.

The arts, then and now, are delicately intertwined with the political landscape. Jubilee Arts recognised that artistic activity should not be simply a personal reflection of individual artists, disengaged from the world around them, but rather collaborative and participatory, projects that could combine activism and intervention, be community focused and issue-based as well as artist-led. This led at times to clashes with their local authority in terms of funding support; twice Jubilee had grants entirely removed overnight by Sandwell councillors, both times the decision overturned within days by intense lobbying and argument. Sandwell was generally a Labour run local authority – at one point, there were only two Conservative councillors (out of a total of 70 seats), who celebrated this fact by posing in a phone box in Wednesbury, claiming this was where they held their group meetings. There was a joke at the time that if you wanted to be a councillor then it was essential join the Labour Party, which led to some supposedly left wing members being ‘to the right of Genghis Khan’. You needed a sense of humour in Sandwell. One councillor, trumpeting the fact that the borough had the lowest charges for Burials and Cremations in the West Midlands soon found his comments used in a local newspaper attached the headline ‘COME TO SANDWELL TO DIE.’ However, members of Jubilee Arts were not afraid of actively engaging with elected councillors, whichever their political views – indeed, viewing them as advocates of the community in their own right, partners in planning and delivering activity. Indeed, Sandwell councillors often applied to join the Jubilee board of their own wish, elected by the membership of the organisation, rather than being imposed on the organisation as a condition of council funding.

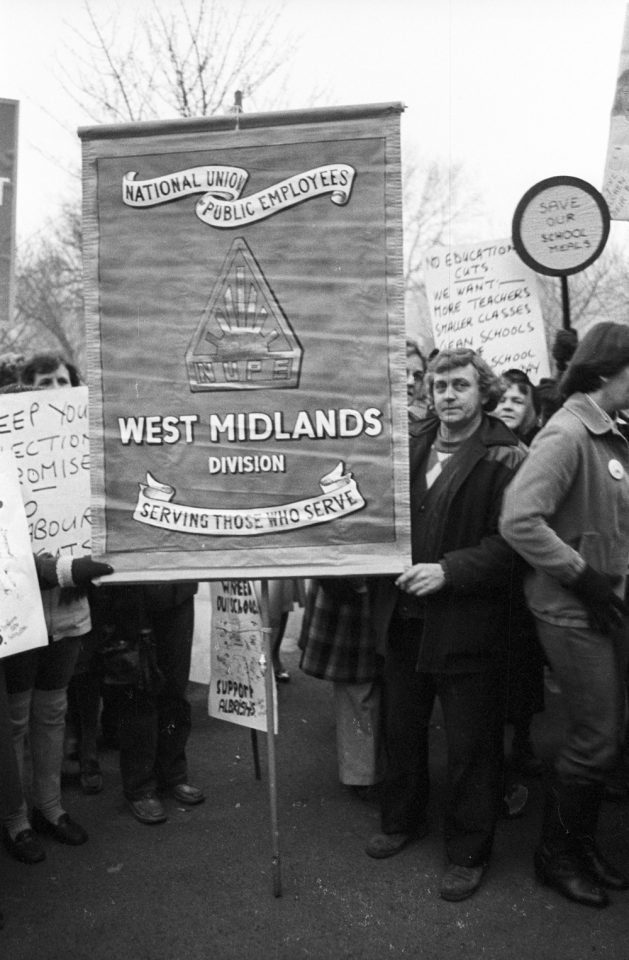

Councillor John Edwards was one. He recalls: “When Sandwell came into being there was a lot going on politically, that’s for sure, lots of activity. The National Front, as it was then, were active in borough, the coal strike was building at that point, the direct labour organisation in the borough was being attacked by the Conservative party and after that, I have to say, the right wing of the then local Labour group, who thought the private sector could do contracts better that the people who worked in our own Public Works Department. There was always some activity to counteract as well the positives we were trying to encourage in community development. It was a lively place to be.

When I sat on their board, a member of the governance they had at Jubilee, it was fairly loose. It was designed to represent the communities they worked with, those who funded them, as well as activists in the borough who had something to say and something to contribute. I happy to do so because there were a lot of people relying on practical support around banner-making, activities to help inform, leaflets, publicity, all the rest of it. They were very much a street organisation and that very much suited my politics.

A lot of activism was fairly spontananeous. It was easier to engage people in political activity and street activity, direct politics if you like. We did that fairly easily – anti-rent increase demonstrations, school dinner staff protests that were going on and so on. We would campaign and agitate over a whole range of issues.

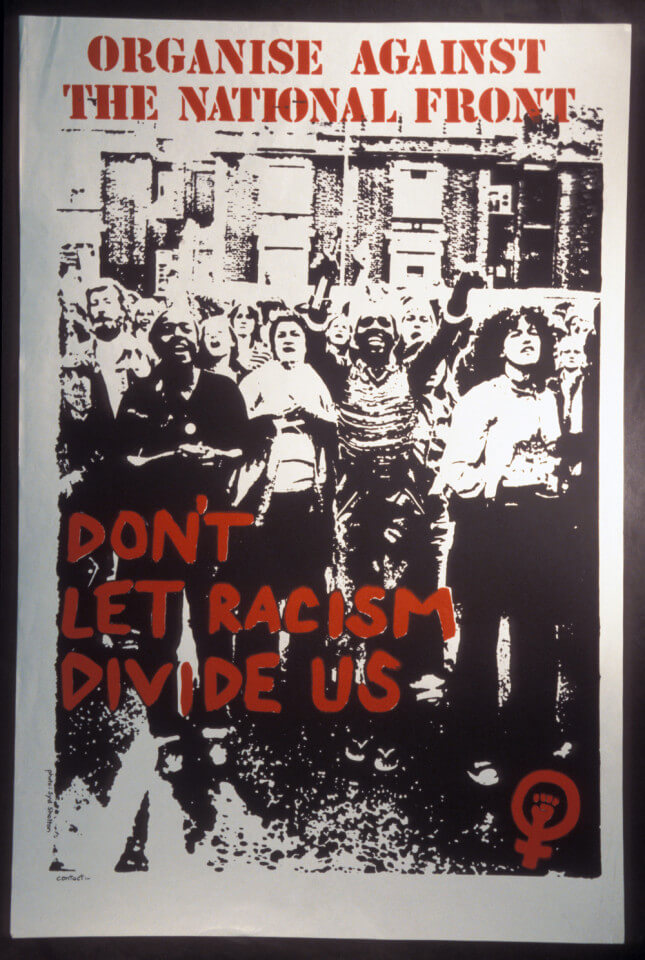

In response to the presence of racists and fascists in the borough we created SCARF, the Sandwell Committee Against Racism and Fascism; that took off and became a powerful movement in Sandwell, one that could which could generate three to four hundred people on the street when we needed to. I remember the time we surrounded a public meeting the NF were holding in Cronehills school in West Bromwich. The place was literally surrounded by local people, who saw it as an affront to their school and their community and wanted to do something about it and were prepared to come out and do something.

Were they golden days that have been overtaken by protests on Twitter? Maybe they have but I’m not sure it quite has the impact, that street presence that demonstrations used to have. Clearly a lot of issues are not even decided locally anymore, so it takes away a lot of local choices anyway and therefore lots of interests, activity and campaigning where they may have applied before.”

After making critical comments of the Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer, in 2021 he was deselected by the Party. He stood as an Independent, lost to the official Labour candidate and was duly ejected from Party membership.