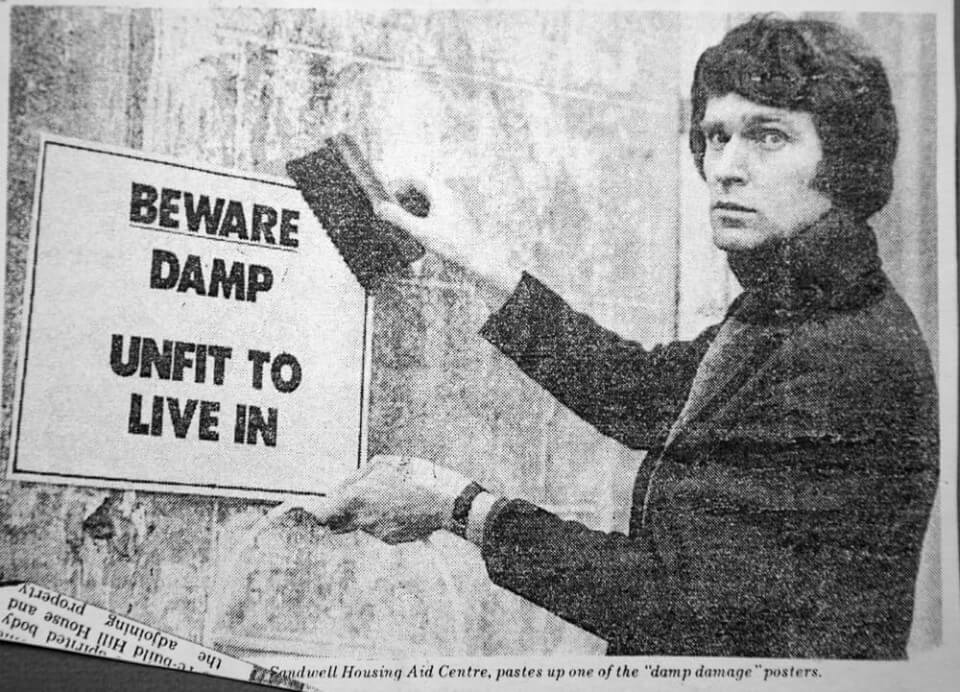

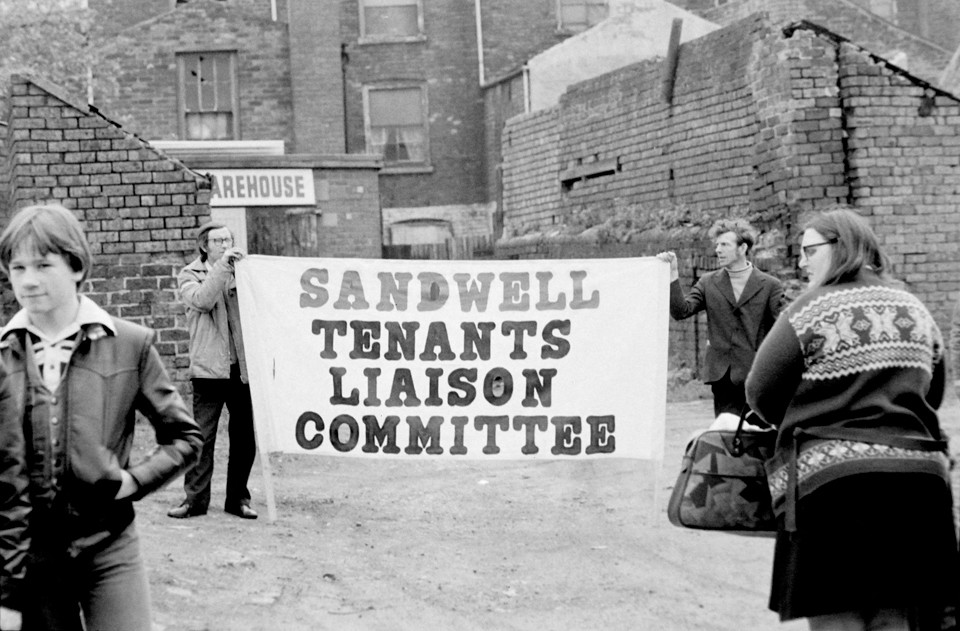

In the 1970s, Jubilee Arts developed working methods which were primarily responsive to the needs of local groups and issues that arose from the community itself. Theatre and play work on council estates such as Friar Park, Yew Tree, Langley or Whiteheath, led to contacts with Sandwell Tenants Liaison Committee, for whom decaying housing stock in general and damp in particular were the major issues of the day. Sandwell had some 57,000 council tenancies and high blocks that were described in the press with headline such as ‘Horror Storeys’ or ‘Not Fit For a Tramp’. For radicals and activists these community artists offered a wide range of techniques for spreading their message, through festivals, printshops, video and theatre.

So Jubilee lent their 35 mm camera to community groups, made videos with local people, created and performed shows in solidarity with campaign groups, helped make placards, banners and badges, printed posters and t-shirts with silkscreen, made flyers with a Gestetner machine. This work could involve youth people making film about ‘Dole Q Youth’, it could involve trade unionists campaigning for a safer work place, school dinner ladies producing banners and posters about job cuts and low pay; it might involve a group of moms in West Smethwick making a film about road safety or posters highlighting factory pollution – all giving voice to local issues of concern.

Despite starting out as a theatre group, Jubilee employed an array of media tools quite early on. The EIAJ-1 Sony reel to reel format from the early 1970s offered black and white video recording and playback on half inch magnetic tape on a 7 inch diameter open reel, with portable units using smaller 5 inch diameter reels. At first, over weekends, they were able to borrow some state of the art kit like this from a friend who worked at BBC Pebble Mill.

In 1980, when this photograph was taken, we must remember that there were only two television channels, BBC One and BBC Two, alongside the ITV regional franchise network, of which ATV broadcast to the Midlands. The idea that you might put the tools of media production in the hands of ordinary people was then a radical one. Most British community artists of the time believed that by giving people access to skills and technology, that putting the means of cultural production into the hands of working people was essential for a healthy democracy, to ensure visibility and more equal representation, to combat erasure and censorship. Peter Dunn and Lorraine Leeson, of Docklands Community Poster project, put it this way: ‘The aim is not to seek consumers of radical culture/ideology but to generate producers.’ For individuals involved it was about consciousness raising, developing both confidence and abilities, leading to a critique of their environment and a desire to take action to change things.

Of this process, graphic designer Andrew Howard, who worked for Islington Bus Company, another community arts organisation in the 1970s who operated with a mobile resource, noted: ‘Observation is not a passive act and is not the same as simply looking. It is a reflective process that demands constant questions—what I call interrogation. It begins by looking at what seems obvious and everyday and by questioning what we think we know. In turn this leads to the third element – discovery – where things are revealed or inadvertently uncovered as a result of close scrutiny.’