Is there such a thing as the good old days? Longing for a time when things were easier, or perceived to be somehow better, less complicated or turbulent?

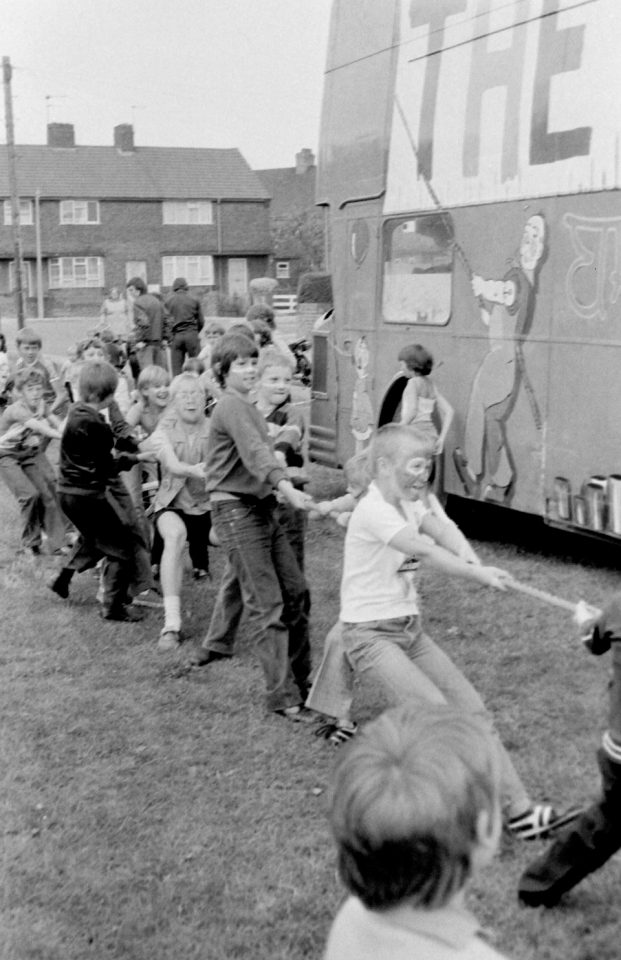

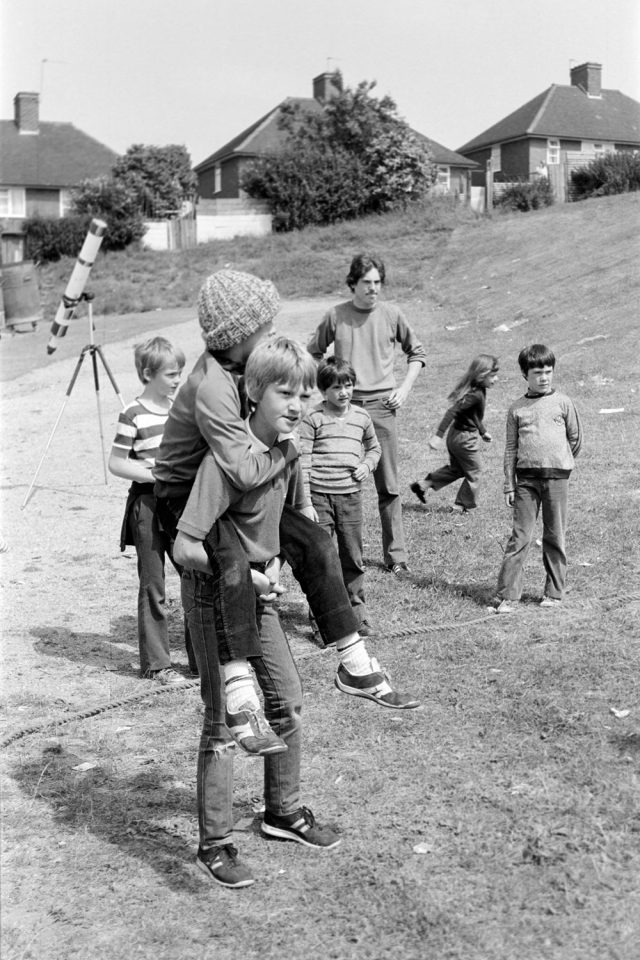

To be able to climb a tree without anyone telling you to get down, building a den in a forgotten corner from scrap materials filched elsewhere, to spend the day exploring a disused canal line or railway embankment, going fishing in a reedy pond, to wander through the ruins of an iron foundry; autobiographical memories for which perhaps there are no photographs to record the moment as a memento.

Yet here is one. A gang of lads perched in a tree. One of half a dozen frames made in Oldbury on patch of overgrown wasteground. In some they are daring each other to jump down from the heights. And they do jump, fall through the air like Icarus. They say no camera can capture magic, but they do capture time, freezing a moment that is passing, that will never happen again. A shared experience is recorded, though perhaps not in perpetuity. The shutter button is pressed, the film wound on, then with a chemical process the negative is made of cellulose film, a highly flammable medium, a positive then printed on paper, perishable. Now we insatiably capture memories as ‘experience’ and compulsively upload them to social media. Billions of them daily. ‘Here we are having fun.’ We live on, forevermore, in the digital afterlife – or, at least, until the satellites and servers fail.

The writer Javier Marías was of the opinion: ‘Life cannot be narrated and it is extraordinary that we nevertheless have tried throughout the centuries to tell what cannot be told, whether in the form of myth, epic poem, chronicle, annals, minutes, fable, legend or canticle, blind man’s ballads or corridos, gospel, hagiography, history, biography, novel or funeral eulogy, film, confession, memoir, report, it really doesn’t matter.’ He doesn’t include photography in this list.

The idea of nostalgia was caricatured by Monty Python with their ‘Four Yorkshiremen’ sketch, as they try to outdo each other with their accounts of deprived childhoods. The word itself is derived from two Greek roots: ‘nostos’ meaning to ‘return to one’s native land’ and ‘algos’ referring to ‘pain, suffering, or grief’. Over 300 years ago, a Swiss physician, Johannes Hofer, coined the word, considering it as a disease caused by homesickness – a disease that could have, it was believed at the time, fatal consequences. Dr. Krystine Batcho, a professor of psychology at LeMoyne College in New York, rather explains it this way: ‘We pick and choose. The memory process not only is selective, but it also distorts to some extent. We do idealise things on occasion. By the way, this is a two-edged sword because just as we can idealise and romanticise and therefore distort the accuracy of memories, we can go in the other direction.’ Memories shape our own sense of self, of our group identity and our understanding of the world at large. She points out nostalgia is a comforting emotion, for an older person this is highly personal, recalling something enjoyable or momentous in their past life, but for a younger person, dissatisfied with the present state of affairs, it is a historical nostalgia, a belief that things must have been much better in the past.

A tree to jump out of. No health and safety warning. No digital tracking.