It’s well after midnight. Teenager Peter Singh is working in a temporary darkroom set up in a store cupboard behind the stage of the Big K Social Club. He’s developing and printing photographs from the previous day for display in the hall as the morning picket arrives. He has a newfangled Sony Walkman plugged into his ears, with only a couple of tapes. Various people are trying to catch some sleep on the stage, behind the curtains. “Who could forget that nightly chorus of Peter singing along to Wham’s ‘Last Christmas’ – again and again and again…” recalled Ron Collins.

The year long miners’ strike of 1984-1985 was one of the most bitter industrial disputes Britain had ever experienced, causing immense hardship to thousands of families within close knit and co-dependent pit communities from Scotland to South Wales. After two successful miners’ strikes in 1972 and 1974, the Ridley Report of 1977 proposed how a Tory government should fight the unions – particularly the NUM – by militarising the police, building up coal stocks and setting up dual fueled power stations. There were also covert operations where spies were placed within mining communities, the organising and financing the dissident back-to-work movements, and even strong allegations that the President of the NUM, Roger Windsor, was recruited by MI5 to undermine the strike.

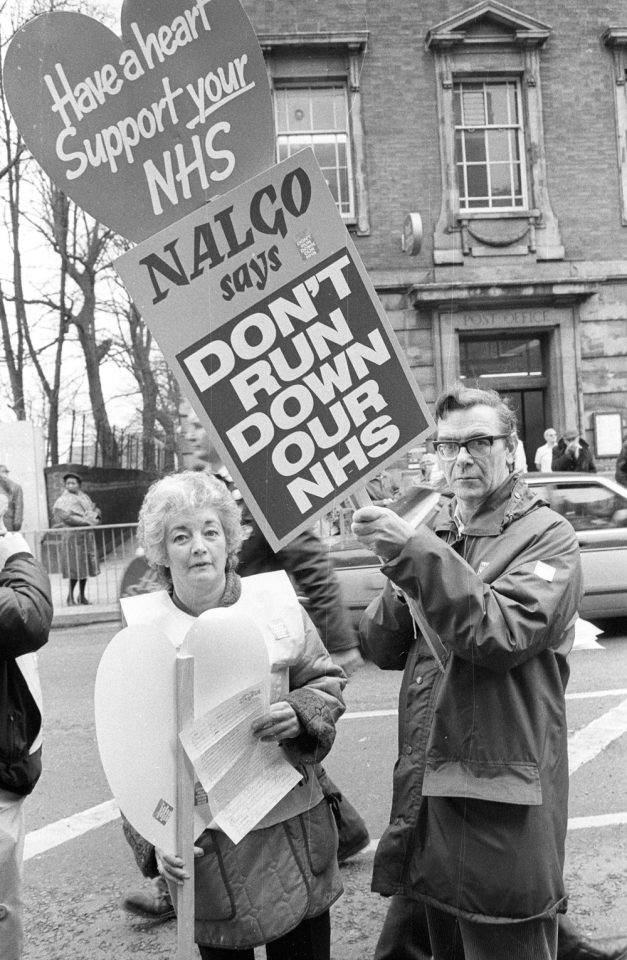

As violent confrontations between police and pickets ensued, Margaret Thatcher soon characterised the strikers as ‘the enemy within … much more difficult to fight and more dangerous to liberty’. Seamus Milne, who wrote ‘The Enemy Within: The Secret War Against the Miners’ some 10 years later, presents a powerful argument that everything we see today, a gig economy, low pay, an eviscerated welfare state, and a failing NHS, can be directly linked to the breaking of the miners’ strike of 1984-85.

Kellingley colliery in North Yorkshire, which started production in 1965, was a deep coal mine with an estimated 90-100 years of reserves, a designated ‘super-pit’ with over 2,000 miners, most of whom lived nearby in nearby Knottingley. Many of these had relocated from Scotland and Durham to work at the colliery, having lost their jobs as pits that closed in the 1960s. One of those was the NUM Branch secretary there, Davey Miller, called upon Banner Theatre to come to Knottingley to perform in solidarity with the strikers. – he had been interviewed by Banner’s founder Charles Parker in 1974. Ten years on, Miller had a broken leg after being charged by police horses on the picket line. He later recalled: “If the miners were the Spartans of the working class, then this was their Thermopylae… There is a difference between dying and murder. Our industry was murdered.”

Dave Rogers of Banner recalls: “We did busking on street corners, performed in miners’ welfares and went to miners’ support groups. We would be in a situation where someone got beat up on a picket line in the morning, we’d write a song in the afternoon and perform it at a strike social in the evening, so it was a really organic relationship with the strike… I think the socials in the miners’ strike were fundamentally important. The atmosphere was just explosive. There was a big infusion of people and exchange of ideas.”

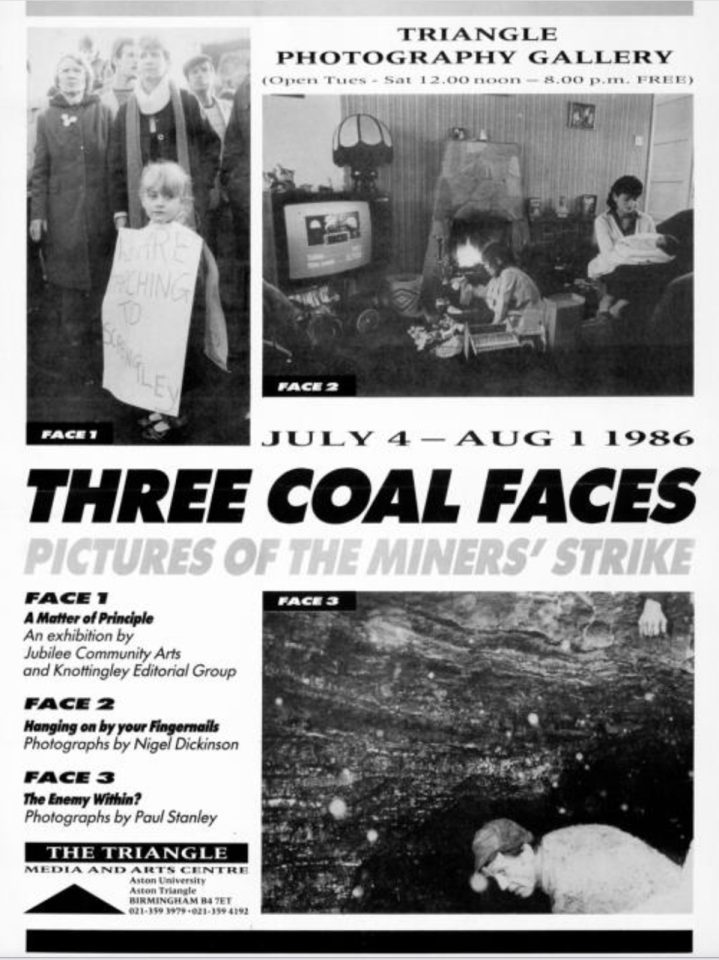

Banner Theatre called on members of Jubilee to help support their tour of the Yorkshire coalfields. The Jubilee playbus, loaded up with various volunteers associated with Jubilee and Banner Theatre, and Smethwick Music Workshop music workshop, arrived in Knottingley pit village to help provide some pre-Christmas entertainment for the strikers and their families. A busman’s holiday, you might say. Music performances, children’s art workshops, shadow puppets, all the tricks of the trade. They also began to design and make a new banner for the NUM branch, and document the day-to-day progress of the strikers, their supporters, and the highly active women’s groups. They focused on making photographic self-portraits, using a long cable release, developed and printed overnight and displayed on a washing line at the Big K. These proved immensely popular.

The reason for this is that they offered a powerful counter narrative to the images of the strike produced in the media, the ‘official history’ as it were. Many were critical of mainstream media bias, with the repetition of images which seemingly showed violent pickets forcing reluctant police officers to respond, images of strikers apparently terrorising innocent people merely trying to exercise their right to work, images of property allegedly damaged by miners. While these photographs were initially intended to be seen by the people who had been photographed and by their friends and colleagues, offered to a specific known audience, their alternative narrative struck a wider chord. These are images that arose as a part of a collective activity, rather than as a detached record. As the strike ended in March 1985, a local group of activists in Knottingley gathered them together into an exhibition ‘A Matter of Principle’ which they toured widely across the coalfields and beyond. At the heart of this work was local people exercising the right to present themselves, in their own way and on their own terms.