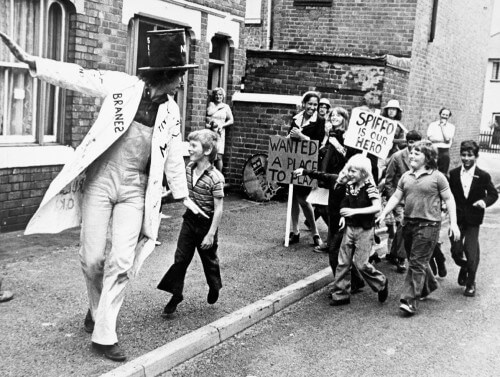

Warley youngsters had a wizard time acting the fool when the curtain went up on Sandwell’s street theatre. The Wizard of Langley was one of a group of actors touring the area to remind children of council-run play centres. The street theatre enticed youngsters to join in with the cast and then led them in Pied Piper style to their neighbourhood play centre. The project started yesterday at Barnford Park, Smethwick, and Langley Hall and continued in other areas of Sandwell through out the week. Mr. John Titterington, Sandwell’s play organiser said today: “The actors aim to attract the children’s attention and then to show them where their local play centre is.” The centres lay on entertainments and adventure to fight summer holiday boredom among school children.

– Evening Mail, July 24th, 1974

It began with the actors processing down the street. The cast: Spiffo the Wonder Man, Mr No-All, with a Clown and someone dressed as a big red monkey, with guitars, bass drum, kazoos and tambourines and singing (all together now)

We’ve come to find a place to play

Why don’t you come along?

Come and play some games with us

And help us sing our song.

We sing a lot. We play a lot.

There’s lots of things to do.

We’ll we do them all much better

With a little help from you.

They would process along until they came to makeshift goalposts, to find there was no football to kick about. The monkey and clown would decide to have a swimming competition, but they had no water. This is where Mr No-All came in, with the suggestion they all go to the beach round the corner – and, of course, the children would shout that there was no beach round here, mate. Other daft suggestions (the dafter the better) from Mr No-All – such as ‘Let’s climb the mountain at the bottom of the street’ – would soon be shouted down. Spiffo would then intervene. Spiffo the Wonder Man wore a splendidly imposing cape with mystic symbols and traditional pointed hat.

Spiffo asked the children to suggest how to get to Mars. Mr No-All suggested a giant catapult with extra strong elastic. Spiffo – rather Zen like – tells them the only way to get there is to ‘think it’. The children had to then learn Martian language, using bleeps. And son on…

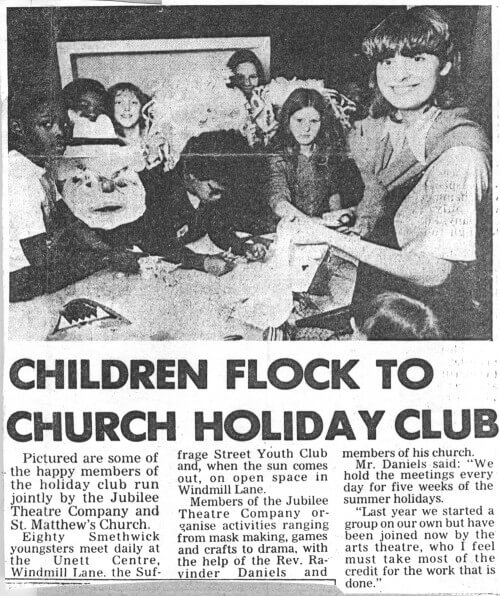

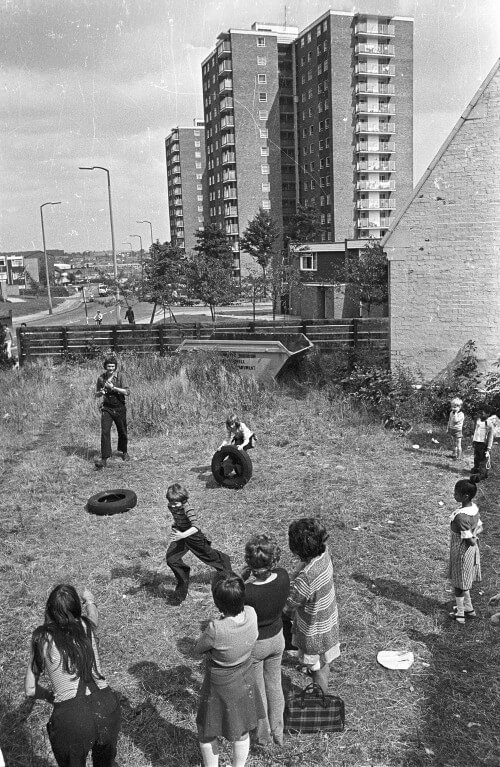

After going to various locations around the borough and successfully delivering children to the new playcentres, the Jubilee Theatre group then spent three weeks at a space in Whiteheath, below a block of flats, putting on a series of plays, concerts and film performances.

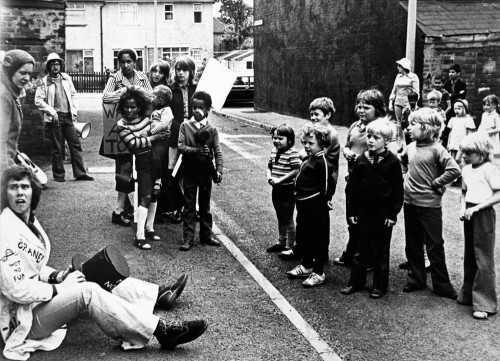

Steve Trow recalls it this way: “Whiteheath was the very first Jubilee project. As a group we first worked with the Playleader’s Department in this area where there was an enormous concentration of children in a high-rise block with no provision for any kind of play in the area. The original deal in 1974 we agreed with them was that we would do a street theatre performance, which was with a monkey and the big bass drum going around all the play centres for a week when they opened for the summer. We would go to each one and two or three neighbouring streets, perform and run street games to gather up the kids and bring them back to the playcentre to launch it. Then we were given the centre in Whiteheath to run ourselves. We were thrown straight into organising it. Chrissie Poulter had done it before with Interplay in Leeds and we relied heavily on her experience – she was 20 at the time. I knew nothing about it and hadn’t worked with kids before. There we were on the street with the toughest kids in Sandwell. So what’s where we learnt quite quickly and where the whole model of how we worked with kids was developed. And then this model branched out to performance work with adults, creating these popular pub shows over a number of seasons.

“We’d start off marching down the street, singing some daft song. The intention was to gather as many people as you could and lead then to the play centre, which was opening for the summer. Then we’d stop and suggest ideas, we could do this, play a tag game, a mock sword fighting game, a drama game, then by the time we’d arrive the play centre we’d have about 60 kids with us and we’d introduce them into the kinds of things they could do there, and at the end of the day hand them over to the play staff. There were no laws then about appropriating children and marching them off…”

The Keefe kids have been sliding through the summer. Filling in time in the weeks away from school has been easy for the family from Durham Road, Rowley Regis. For the Whiteheath Play Centre has been the favourite summer haunt of (from the left) five year old twins Sisan and Steven, Lynn aged 7, James, 9, Patrick, 11, and Thomas, 14. And today their mother, Mrs Rita Keefe, thanked the Birmingham University students who ran the centre for giving her a holiday break. “There used to be nowhere for the kids to play,” she said today. “They annoyed neighbours if they played outside and got under my feet at home.”

“The students have been absolutely marvellous,” she added. “The scheme has kept the children out of trouble and taken a great weight off my mind.” The Keefes are among dozens of youngsters who have attended the Whiteheath Community Centre over the past five weeks. The students have acted out plays with the youngsters and organised other pastimes for them. A Sandwell Recreation and Amenities Department spokesman said today that the project has been “an enormous success.”

– Midland Chronicle, August 1974

The work in Whiteheath was a tremendous success. Elsewhere, some of the sessions were less productive. One worker report from the Harry Mitchell Centre, Smethwick, 28.8.74, stated: ‘Generally speaking, the endeavour, creative ability and imagination of the children was not of a very high standard. Like all children, they found it difficult to concentrate on anything for longer than half an hour. They disliked anything which required any thought. I asked most of them, at some time or another, what they did when they were not at the Centre; most of them stayed in bed in the mornings or watched television. In the afternoons they watched television. None of them played outside, or inside for that matter… I feel the scheme would have been more successful if it had been situated near a playcentre and also if it had been for all the arts instead of just drama. Many of the children came to the centre because they had nowhere else to go; thinking that it was a playcentre, not because they were interested in finding out about drama. Therefore, the children who were interested were held back because those who weren’t were constantly interrupting and wanting my attention.’

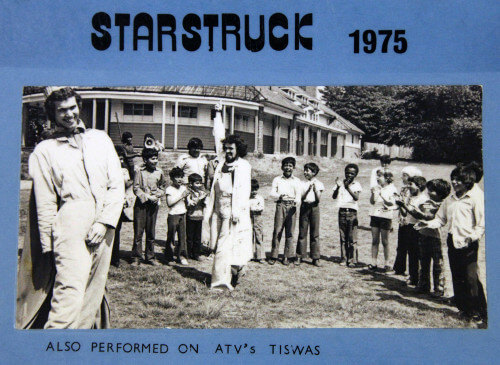

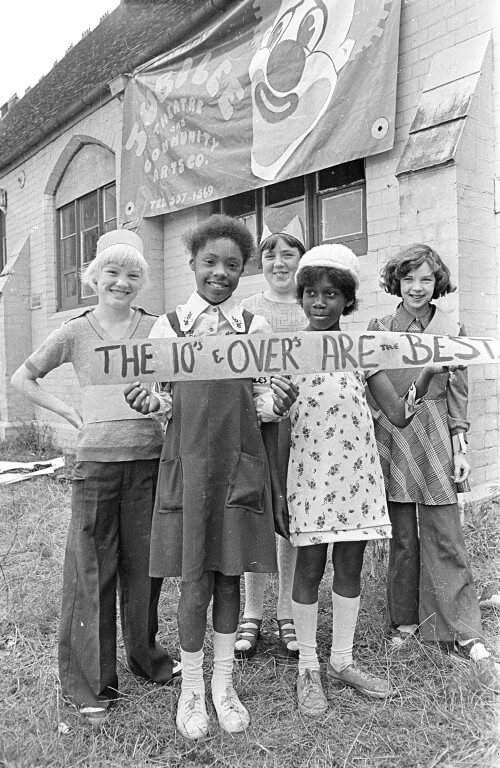

The company learned ‘on the job’ and adapted. At Xmas 1975, they toured a participatory show to playcentres, concerning the confrontation between Grabitall, a malignant evil genius from the pages of Victorian melodrama, and Gwyndraf the wizard and his assistant Blotto the Clown. The children were invited to repair the wizard’s magic machine, which Blotto had inadvertently broken and then recover it from Grabitall, who had stolen it. The play involved a series of games designed by the children to outwit the villain.

The following year, again encouraging children to come to the playcentres through drama interventions, they added film to the mix, making super 8mm films with the children as well as devising plays. The introduction of cine film material led the children to undertake their own surveys on people’s feelings about kids in the area, done by taking lists of questions from door to door. In time, uncovering local issues, this would lead to campaign work with tenants groups.

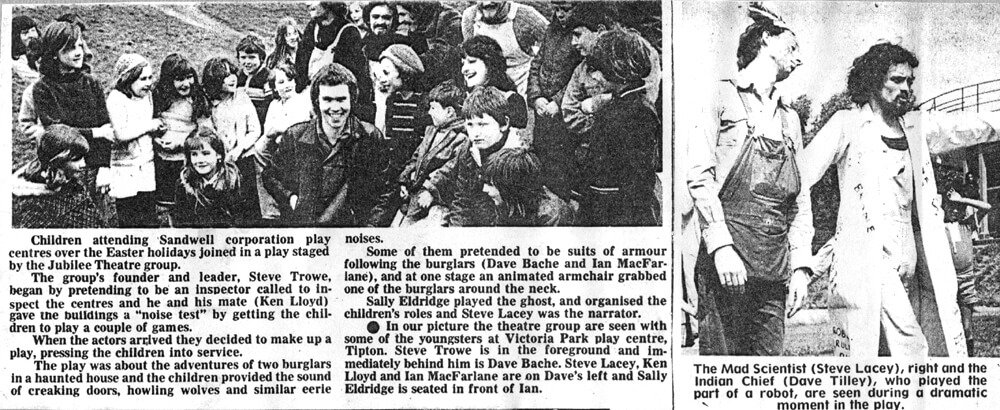

One drama routine was for The Compulsive Actor (a white faced clown) to burst into the playcentre and ask the children if they had seen the rest of actors. He explains he has to act or else he gets ’the shakes’. The children were enlisted to go on a search for the missing Thespians, eventually finding King Arthur, the Mad Scientist and the Indian Brave. They then find a place to perform a play with King Arthur cast as The Prime Minister of Hard Work, the Mad Scientist as Merlin and the Indian Brave as Sir Laffalot. The Compulsive Actor is given a role as a litter sweeper, and the children recruited as robots. After the playmaking, in the afternoon the group worked with the children playing games.

At Spon Lane the night before the actors visited, the play hut was broken into and sweets and 20p stolen. Ever on the alert for fresh games, the play leaders organised the children into groups to re-enact the break in. This was well before Crimewatch (although Kate Organ’s younger brother went on to be the producer of that programme and the person behind Video Diaries on the Beeb.)

Members of the group devised and performed a dramatic ‘story’ which took place in local playcentres during the school holidays. The event, which was halfway between a performance and a narrated story, involved children and actors in creating and exploring the comic situation of two burglars in a haunted house. Both the actors set pieces and the children’s additions were orchestrated by a narrator. At each playcentre the event occurred in the morning; the actors returned in the afternoon to play games and evolve stories and plays involving a a variety of arts techniques suggested by the mornings work.’

– extract from report to Arts Council of Great Britain, 1976/77

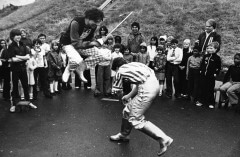

Their activities soon expanded into organising festivals and longer play events with community groups, so by the time of the Queens Jubilee Festival in 1977, there were activities running across several parks, including Jubilee Park, Tipton, Dartmouth Park, West Bromwich, Victoria Park, Smethwick, Haden Hill Park, Cradley Heath. The most popular event proved to be the All England Custard Pie Throwing Championship. Although in this year they changed their letterhead to read Jubilee (Nothing to do with the Queen) Theatre and Community Arts Company, they still received a donation from the Queen’s Silver Jubilee Trust of £2,900.

Kate Organ: “By then, we were operating a three ring circus. Whereas in the first year, four of us did everything, within a few years later there was a core team of people employed, so there were lots of projects happening simultaneously. This would have been a piece of street theatre with is me, Martin and Andy going out and doing street theatre twice a day – as actors really – and somebody would be picking whoever we gathered and working with the play leaders. This particular show we devised was about the making of ‘The Play Machine’. We were sort of spaceship people and we’d got a machine.

The play machine had knobs and things and it spouted out ideas for games and then they’d play games. Andy played the idiot, Martin was slightly naughty and sadly I was the boring one who had keep them in order and remind them that we had to go back on the spaceship. I do remember that even off stage I had to keep them in order. They’d go off and get drunk and they’d be hung over the next morning. They both went on to be multiple BAFTA award winners. Martin went on to work with M6 Theatre Company and then produce ‘Allo Allo’ and ‘Men Behaving Badly’. Andy founded a company called Rationale Theatre, experimental, physical, conceptual theatre, and directed the first series of ‘Cracker’.”

T hese ‘games for the imagination’ (a term used in an early report) inspired the policy and principles of the company, developing over the years into a unique multi-disciplinary approach. There were other community arts groups springing up around the country but most focused on a particular form, whether it be photography, or film, or performance, or print. Jubilee took a multimedia – or mix’n’match – approach, adapting their work to whatever tools were appropriate. And, as Steve Trow put it: “I like to think there is something inescapably in the genes – some basic principles, an irreverence for prevailing dogmas, a fair amount of brass necked cheek, and not taking yourself too seriously.”

Film footage from Whiteheath, 1974

Film footage from the Unett play centre, Smethwick, 1976