In July 2015, the Chancellor of the Exchequer announced his plans to cut £12 billion more from the social welfare bill, a sum slightly less than the £14.5bn given to commercial companies in direct subsidies and grants alone. The Commons backed the Welfare Reform and Work Bill by 308 to 124 votes and Andy Burnham, a candidate for the Labour leadership, admitted that Labour made “a mess” of its approach to the government’s Welfare Bill and the party is “crying out for leadership”. They proposed abstaining from voting rather than voting against it; almost 50 Labour rebels defied this order, a token of resistance. The lack of any effective opposition since then – or indeed leadership – in offering any alternative vision or concrete plans for the country is shocking. We are told we live in the era of ‘the democratic disconnect’.

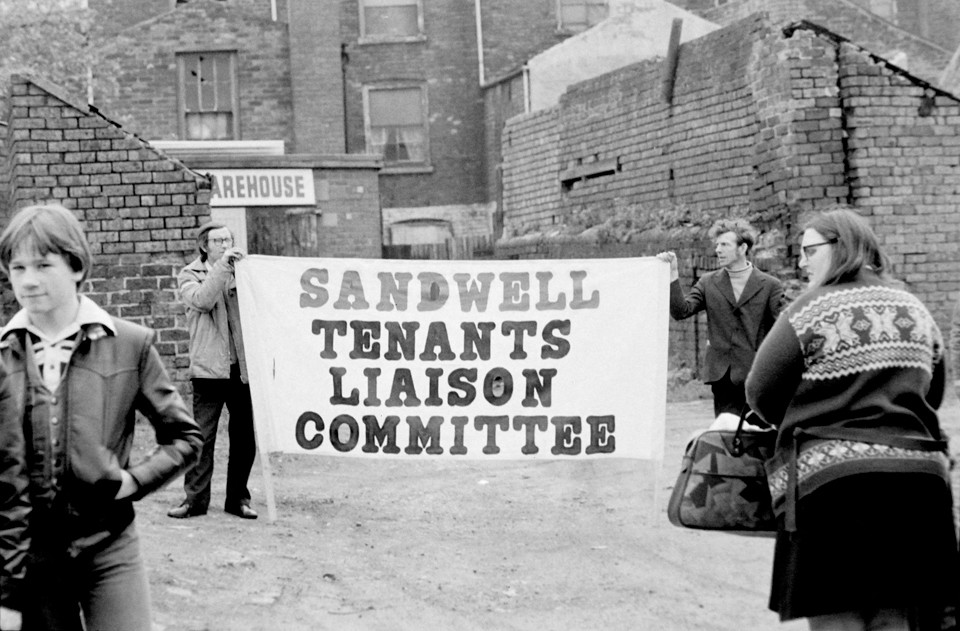

Where are the activists? While taking archive material out around Sandwell we noted the lack of groups engaged directly with issues in their community – a stark contrast with the images in the archive. People worried about the cuts to libraries and services, but as for any direct action?

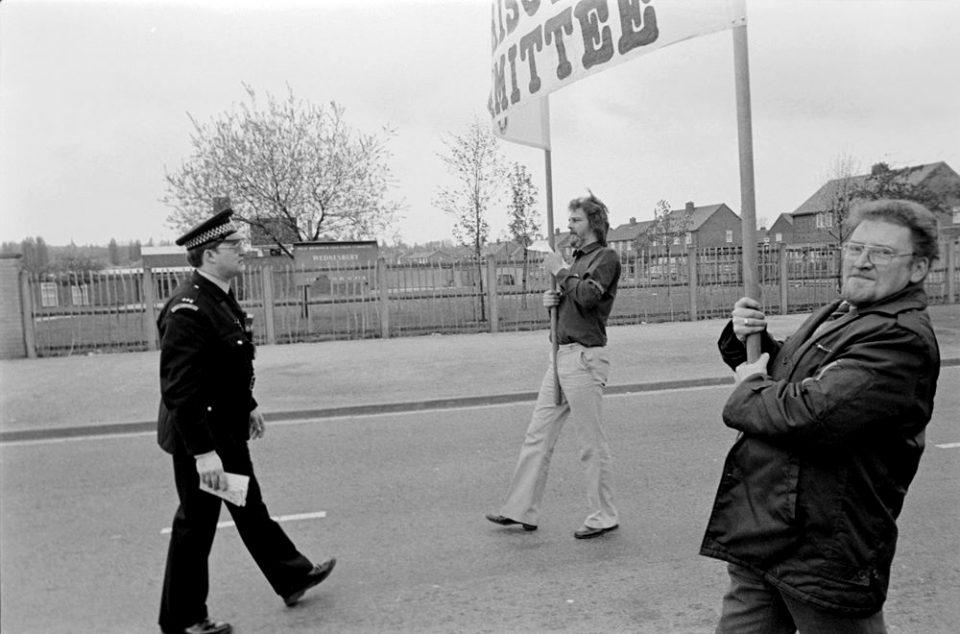

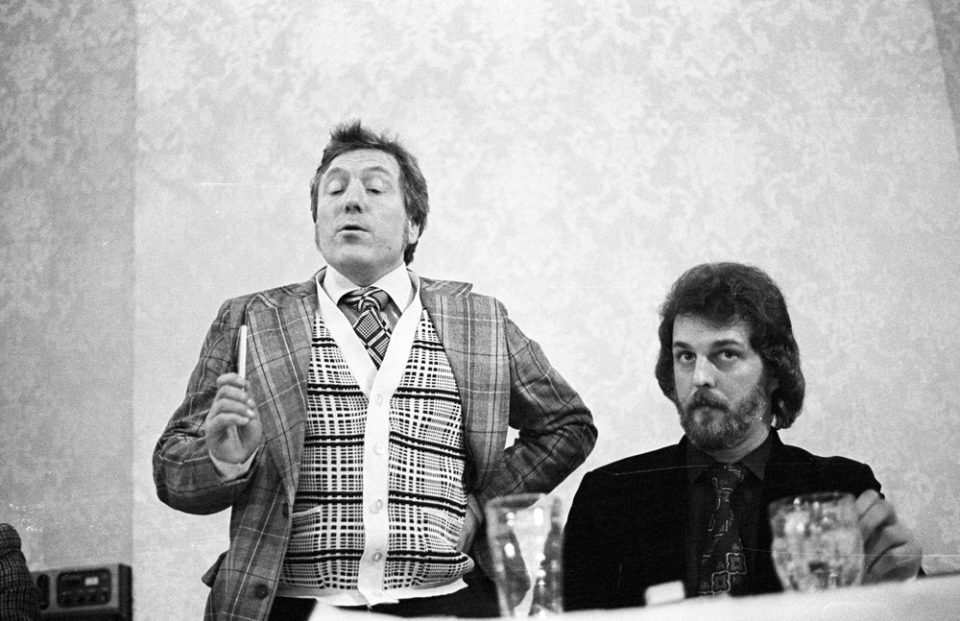

This image is from 1981, taken from the steps of a council house at Wallace Road, at the foot of the Rowley Hills. Mike Peckmore from Housing Aid – an independent group – with the megaphone solicits support for tenant action by going street to street. Peckmore was, to say the least, a thorn in the side of the local council, and many other institutions, an indefatigable organiser of demonstrations, protests and petitions, holder of many a banner and placard. Involved in just about every tenant, anti-racist, and other campaign happening in Sandwell at the time, his politics were hard left and very pro-USSR. A local newspaper in 1977 described him as ‘a tall suntanned circulation rep for Soviet Weekly who at first sight could be taken for a well-groomed member of the Young Conservatives’. His day job was as a Lada car salesman. It never bothered him how many people turned up, it was the declaration of dissent that counted and, as he put it, ‘tackling basic issues head on – unemployment, housing, working people’s standards of living…’ He was a master of the publicity stunt, a Malcom McLaren like provocateur. While it may be easy now for some to sneer at these agitprop class warriors, they certainly could not be called craven or spineless.

One particular incident we recall from this period: an Afro-Caribbean woman with a small child had come to housing aid for advice. Effectively homeless, she had been refused any help by the council housing department. Mike arranged with a group of helpers to take over the local council housing office in Oldbury one morning. There they installed a bedroom for her – bed, table lamp, rug, chair, her suitcase, and so on. He politely but firmly explained to the man behind the counter that she would be living there until further notice. Of course, the press soon arrived in droves, including local TV crews, to tell the story. By the end of the day, she was offered suitable accommodation by the council.

Would this be possible now, especially given the government’s new legislation placing restrictions on the right to protest? The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act (the Policing Act) came into effect in 2022. As the Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, put it: ‘We cannot have protests conducted by a small minority disrupting the lives of the ordinary public. It’s not acceptable and we’re going to bring it to an end.’