With the easy availability of software such as Photoshop and Lightroom – and Instagram filters – images have become super modified and flawless, a reflection of unreality. Yet, imperfect photographs hold magic, according to Heather Greenwood Davis, a Contributing Editor to National Geographic. They do not require technical perfection and composition. Instead, they capture a mood, an emotion, an ephemeral moment. The photographer Jay Maisel believes that ‘gesture is the most important element’ of a photograph.

Instead, we might call this the imperfect moment, for this particular photograph surely hides more than it reveals. What it does depict is a child, whether a boy or girl we can’t determine, running across a patch of grass, who is seemingly about to collide with whomever is holding the camera, possibly a child of a similar age and height. His or her face is obscured by an oversize hat. It evokes memories of your own childhood, the sheer joy of being outdoors on a warm day, the sun on your skin, pelting across a field.

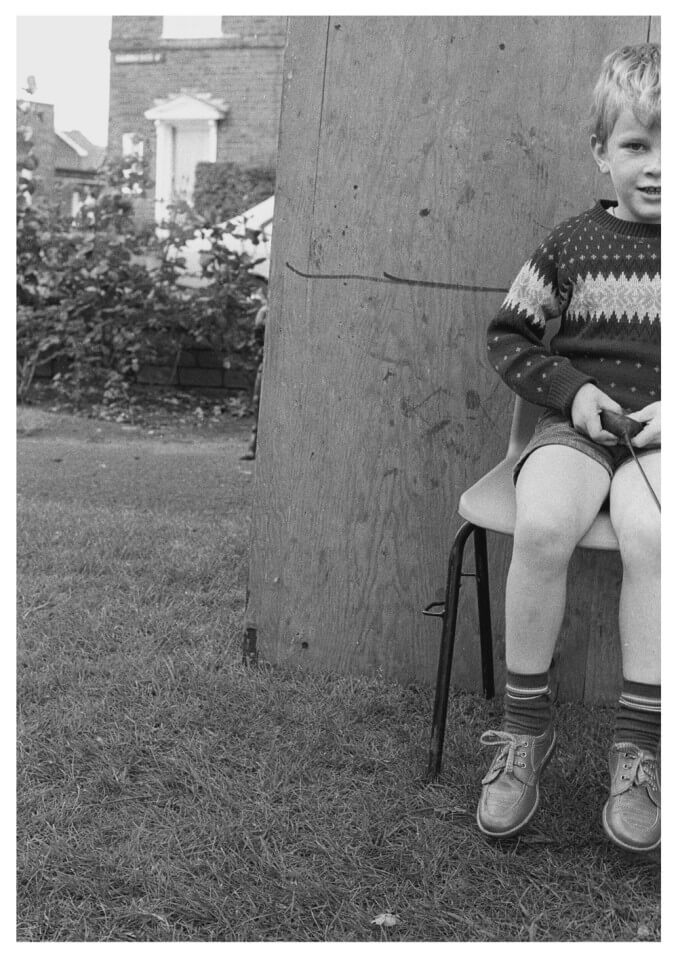

The identity of the photographer is not known, nor is the child whose face is hidden. We do know, thanks to documentation, that it was taken one summer morning in 1981 and that the place is Hateley Heath, a large council estate in Sandwell on the edge of West Bromwich town centre. It captures a moment of a dressing up relay race, where children run back and forth changing into different old clothes. This game was an activity as part of ‘The Bus Project’, a mobile resource for creative play with children and young people.

Community artists then worked mostly outside the institutions of official culture, and were open to the appreciation of all kinds of activity. For Jubilee these included Human Chess, Contest to Find the Most Destructive Vandal, Pigeon Racing or the Plague Game, where ‘The Plague is represented by some soft article – the carrier’s aim is to pass the Plague onto someone else… the game is best played in a semi-darkened room’. The participants in the activities often took the photographs images, the camera handed around, the Bus later used as a gallery to show back the pictures once they had been printed.

Sandwell is a borough which, at that time, fell into all possible indicators of ‘deprivation’ – where, well into the 90s, less than 50% owned a car, and fewer people owned a camera. In 1990, out of a group of randomly selected 64 local people invited to photograph for ‘Sandwell in Black & White’, it turned out only seven of them possessed a camera. Contrast that with today, where everyone’s mobile phone can take both photos and video.

Writing about Rikyū’s theory and practice of tea and the design of tearooms, Professor of Architecture Rumiko Handa noted that by applying ‘the strategy of the intentional imperfect to both the physical and ephemeral surroundings he succeeded in enticing participants to aesthetic and ethical engagements.’ This might also be used to describe this kind of vernacular photography and the work of community artists.

Of course, many contemporary artists use the found image and the snapshot as a source of inspiration, many mining and recycling the past, in a process of self-reflection. And there is a greater regard of the value of these images within museum and archives, partly perhaps due to the decline of analogue photograph itself and the ubiquitous disposal nature of the manipulated digital apparition. Is it real or a fable? As an unfiltered shot of life, they simply remind us that we don’t need to curate the perfect virtual self.