This photograph, dating from the late 1940s or early 1950s, is embossed with the mark of Morais’ Studio, who once could be found at 121 Orange Street, Kingston, Jamaica, then later moving round the corner to Charles Street – as Prince Buster’s Record Shack took over 121, the street becoming the epicentre of musical ventures. W.G. Morais was one of Jamaica’s earliest photographers. Having your portrait taken at this famous studio on the street that ran directly down to the waterfront was, for many thousands, an important part of the rite of passage to England. This photograph traveled down the decades to be shared at a storytelling session at Hill Top Triumphant Church of God in 1989.

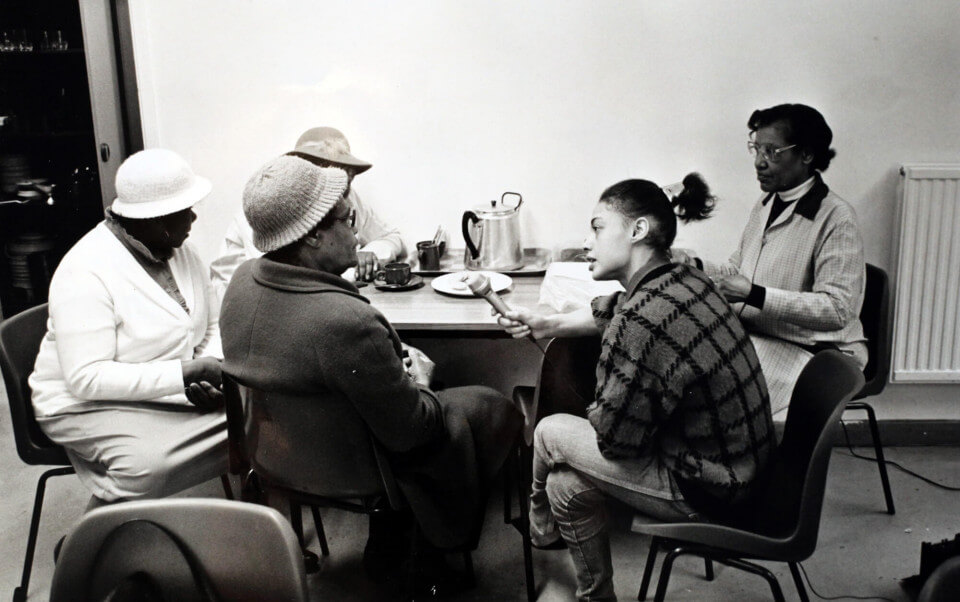

Beverley Harvey shares her memories of the process involved in making an audio tape with this Afro-Caribbean Pentecostal church based group in West Bromwich;

“The Hill Top project was amongst a series of Jubilee projects that sought to engage of Black and Asian communities in enabling and creating opportunities tell their stories in their own voices, to have a say in their representation and identity, to become co-authors in the means of production. While many of these communities were open to participation in the context of ‘happy to have my photograph taken’ it was, however, more difficult to openly share stories of their lives that they knew would be made public. They were very dubious and fiercely private. There were an awful lot of projects that 80% of the time always focused on just racism. Rather we wanted to also share stories of cultural celebration, showing strength and progress, these communities had endured being displaced, had skills and professions that went unrecognised, had been offered false promises in migrating here, experienced the feeling of being profoundly unwelcome in Britain.

The big question was always how do you reach out to a particular community and engage them? Most Afro-Caribbeans locally were strongly associated with church groups of one kind or another. And faith based communities can be very insular, in that they are very private. The challenge was how to start a conversation about engaging in arts and culture. Why is that important? Why bother? I wanted to hear stories of people’s lives. But they would ask me, ‘Why is that important?’ or ‘Why bother?’

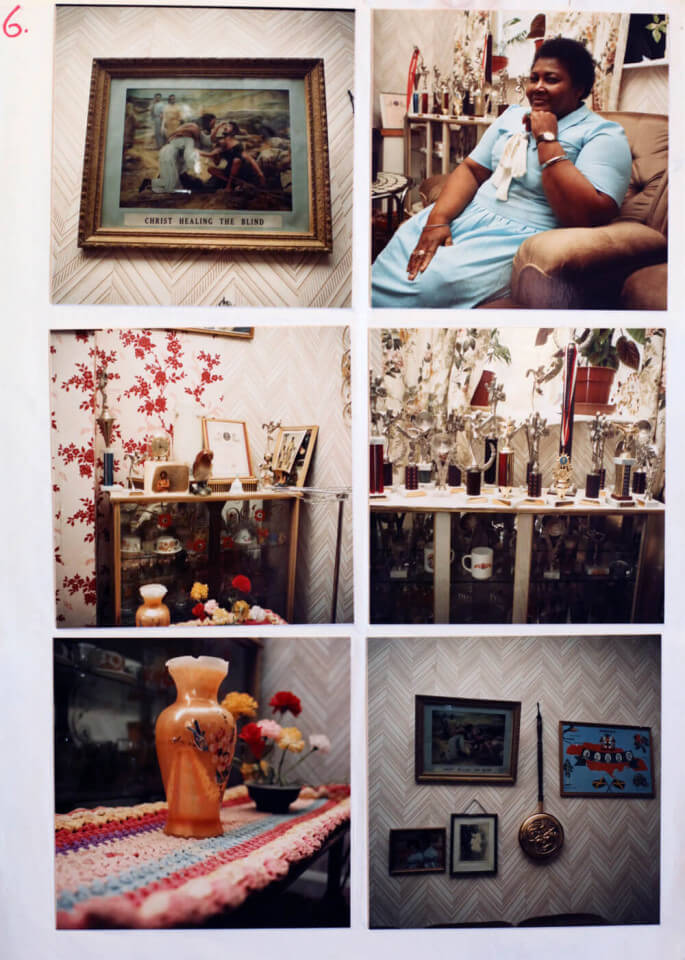

I asked people to bring in photographs of when they were younger, to play a kind of ‘who’s who?’ game. I decided to make the photographs literally larger than life by scanning them and then projecting them onto the wall. It gave a sense of occasion to the meeting and helped start up an enjoyable lighthearted conversation, a way of bonding. So we had all these photographs of members of the group when they were much younger, with beehive hair, top knots with curls, smartly dressed for a pose (often in the same studio in Kingston), gloves, handbags, and kids in frilly frocks, ribbons. Many of these photographs had never been shared outside of their immediate family. But each photograph began a story which the group themselves began to interpret and question. They became both interviewers and interviewees.

Then they wanted to know what could I do for them – what skills did I bring? They told me they needed to fundraise for their activities. They already did crafts and knitting and bible class. They had tombolas, sold crochet and other things. Thinking on my feet, I thought about making an audiotape, a physical object that could be sold, a little radio piece, as it were, to share with a wider community. How much joy and laughter there was in seeing and talking about these photographs – audio would be a great way to capture this.

I then created a small-scale installation, with Errol Brown, like a little Afro-Caribbean front room in the corner of the church hall. It aroused their curiosity. People brought in objects such as a doily, a crochet piece that was starched, and we would sit there and share stories and record them. To this group, art was something in another stratosphere – the ballet or the Tate, something far away – but using these photographs helped them work on a sound piece together. In amongst the memories, often there would a comment which originated from a proverb. For example, ‘That’s why yu seh yu cyaan neva hang your basket higher dan yu can reach it.’ At the outset of the project we had talked about the importance of retaining their identity. In the Pentecostal Church there is always a great of deal of singing, so we talked about using these voices as an introduction to activities happening at the church.

We made little jingles with lyrics, had storytelling sessions – collecting, for example, the memory of someone getting lost on a train journey, childhood recollections of growing up in the islands, their grandparents’ memories, traditional folk stories retold in their own style. At the beginning of the piece, the whole group, of around 50 members, opened with a well-known gospel song – this announced their religious identity, led into stories from childhood memories, accompanied by ambient sounds such as water running or the sound of a train in the background dependent upon the nature of the story bringing the stories to life. Promotional adverts created by the group, often quite humourous in nature, were inserted between the stories. 500 tapes were produced and sold out in the first week. The churches are well networked! It was also used as an edition of the local talking newspaper for the visually impaired in the Black Country.

Using these old photographs offered the group an enjoyable opportunity to reopen their memories of the past and share the story of their journeys through life, a space for reflection and talking about common values – you might say the photographs almost were able to speak for themselves.”