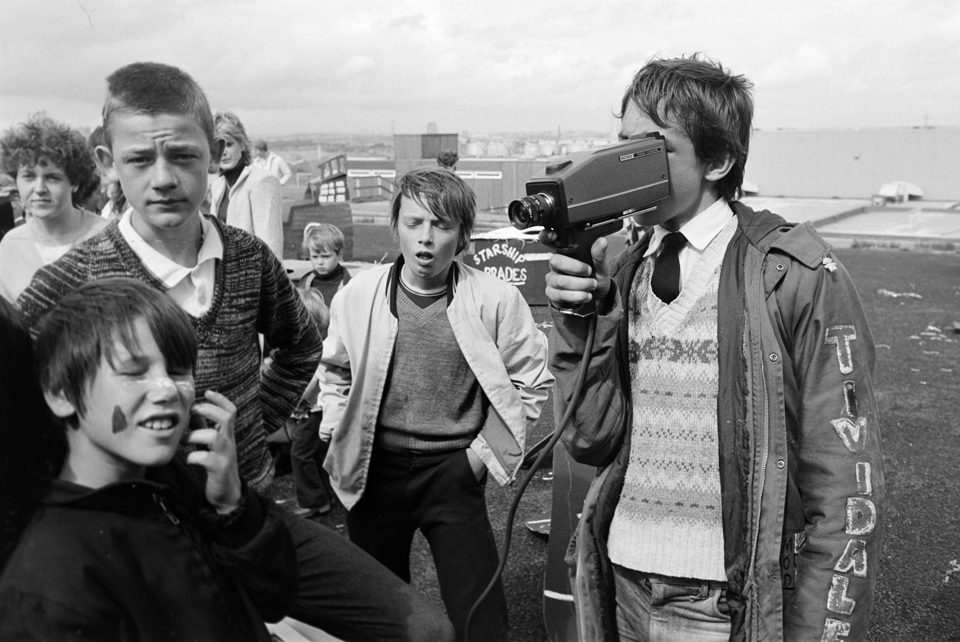

The photographic material in the Jubilee Arts archive offers us a glimpse of the social history of the Black Country within living memory. Over two decades, it presents documentation of people, communities and activities not normally reflected in the official archives of this period, a unique visual anthropology.

In the 19th century, this area changed from being a series of straggling villages – mostly agricultural – to flourishing manufacturing towns, populations quickly doubling, even trebling. By 1929 the burghers of West Bromwich felt confident enough to describe the town as ‘the Chicago of the Midlands’. Over the past 200 years it has been inhabited and re-inhabited by migrants from many places, coming up the Severn valley, from the surrounding rural counties, displace by mechanization and drawn to the new factories of the Industrial Revolution. French Huguenot refugees, escaping religious persecution, brought their enamelling skills here, labourers came from Wales, Scotland and Ireland, squeezing in between the gaps of the foundries and factories, bringing new customs and vitality. After the Second World War, they came from the countries of the Commonwealth, bringing new diversity, cultures and languages; from the islands of the Caribbean, from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Yemen, whose labour was required – and solicited – to rebuild the country. The first Gurdwara in the country was established on the High Street in Smethwick in 1961.

It was without any sense of irony that young break-dancers in the 1980s could express the view that the area was called the Black Country clearly because their families had resettled here from Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, Trinidad – they were surprised to learn that this phrase dated back far longer. Yet it has almost always been portrayed in negative and pejorative terms. In 1851, Samuel Sidney in his book ‘Rides on Railways’, wrote: ‘The majority of the natives of this Tartarian region are in full keeping with the scenery—savages, without the grace of savages, coarsely clad in filthy garments, with no change on week-days and Sundays, they converse in a language belarded with fearful and disgusting oaths, which can scarcely be recognised as the same as that of civilised England.’ Over a century later, the Sunday Times Magazine had no problem characterisng the area as ‘Ghetto Britain’.

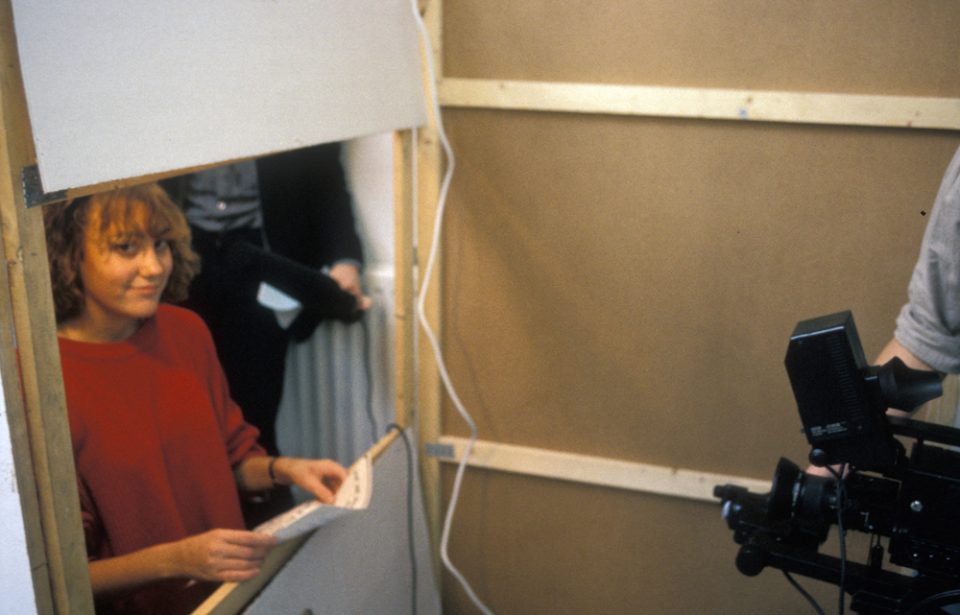

As an organisation, Jubilee Arts championed the need for communities to have control of their representation by challenging stereotypes and through sharing aspects of their life experiences and achievements. In this sense, the archive material provides an exemplary record of the wide ethnic mix that Sandwell and the Black County has become and has a significance beyond the local and regional. In the idealistic 1960s, when social change was seen as possible, community art was seen as a way of giving a voice to society’s disenfranchised and putting the tools of the media into people’s hands, quite literally.