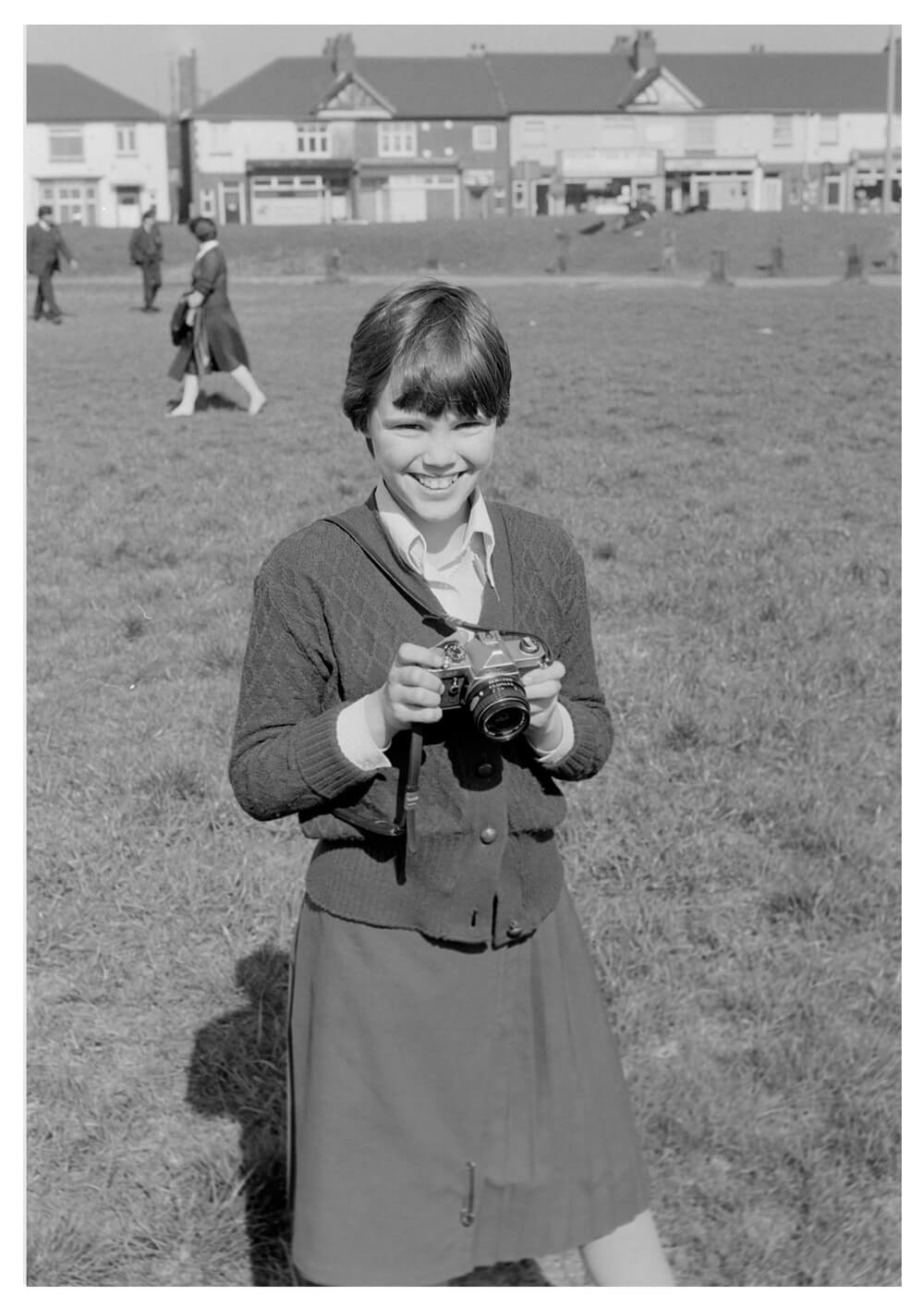

Working at Blackfriars Settlement in South London in the mid-1970s, photographer Paul Carter decided to hand out his cameras to children during holiday scheme. As they began taking pictures he recalled: ‘When you started seeing a different view of the world through the children’s eyes, I realised not only could photography be involved with supporting other organisations in their social action campaigns but the self esteem and creativity of children could be encouraged.’

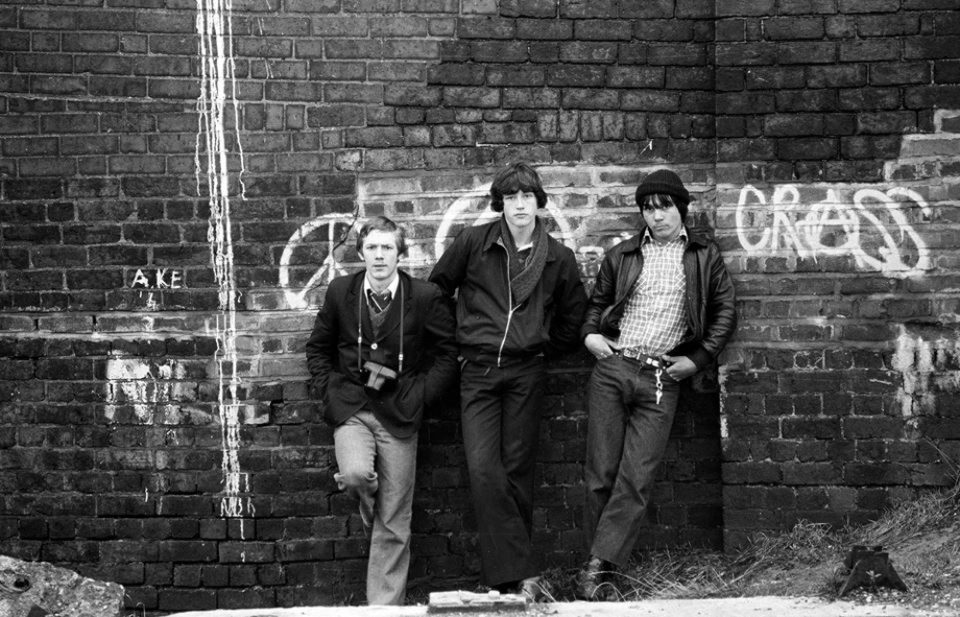

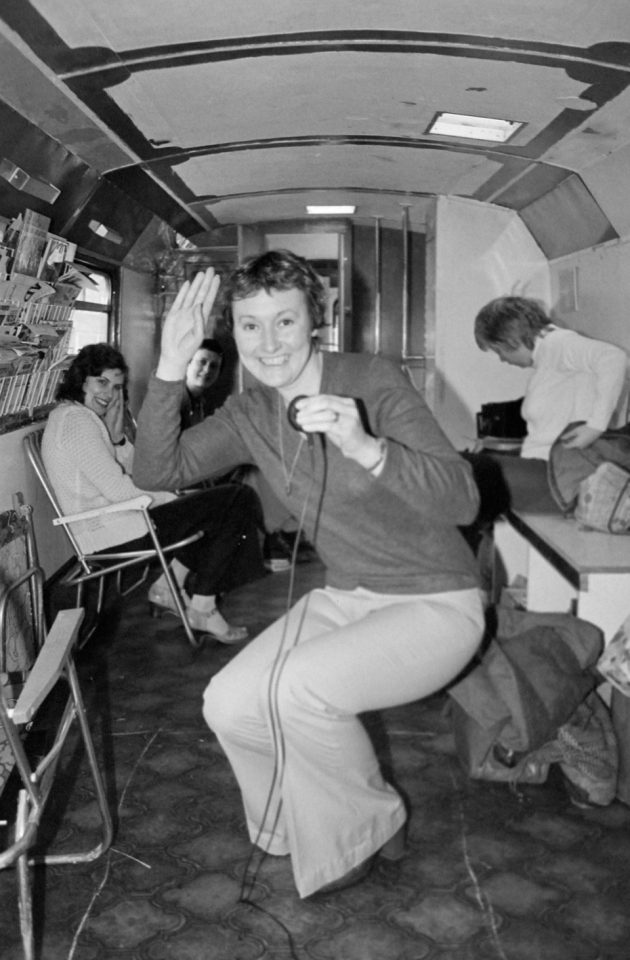

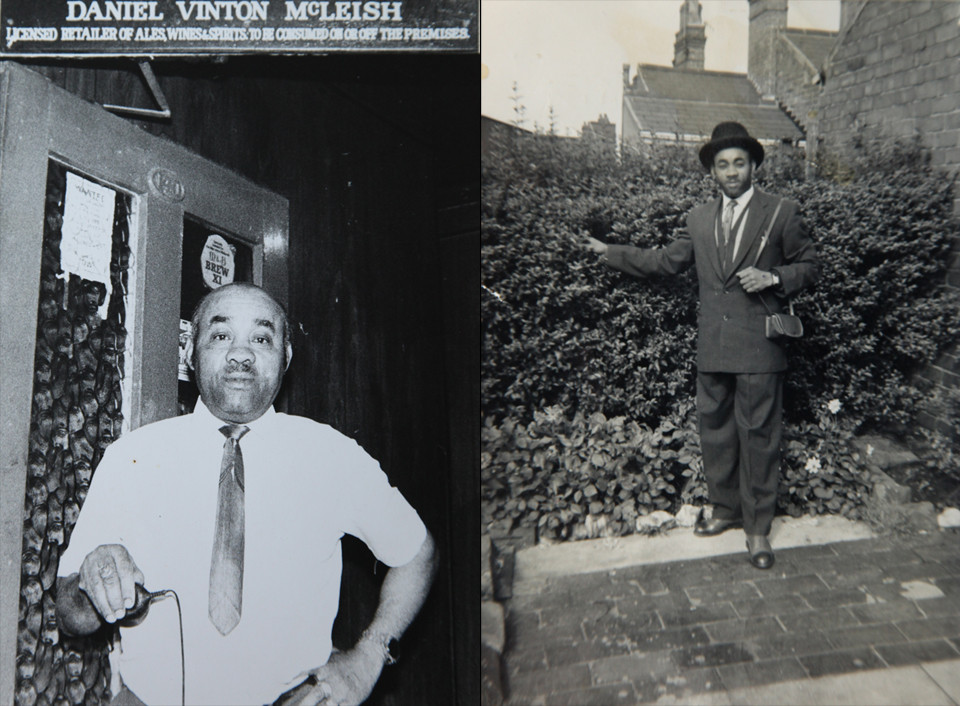

From the moment members of Jubilee Arts purchased a Pentax 35mm camera, they passed it around to people who were participating in their activities, whether that be a playscheme, festival or community campaign – the authors of many of the images in the archive are thus unknown to us. Local people were the main subjects, audience and users of the photographs produced. While the rear downstairs area of the Bus was converted in a chemical darkroom to share the photographic processes, the upstairs space was often used as a gallery space in order that people could understand, appreciate and become more critical of all the photography they saw. At the time, the intention of many community photography projects was to break the monopoly that professional media communicators had over the often stereotypical depiction of their lives and communities. As Steve Trow wrote in 1992, for an exhibition celebrating Jubilee’s 18th birthday: ‘Its value lies in the authentic experience it captures – social documentation and history from a community perspective, made by people themselves. It also provides a narrative of a cultural practice, which sought to put tools in the hands of local communities by engaging directly with local issues and concerns, alongside the representation of an increasing diversity of both working class and ethnic voices.’

Today the camera is always at hand, via our Smartphone, along with the tools to process, edit and adapt, a supercomputer in our pocket. Today we are flooded with images and the impact of powerful images is far less than it was; we mistrust the veracity of photographic representation and its potential for deception through digital trickery.