There is a word for excessive fear of clowns: Coulrophobia. Do you suffer from it? Maybe Ronald McDonald triggers it, or you read Stephen King’s ‘IT’ late one night and couldn’t get that image of the dreadful Pennywise the Dancing Clown out of your head, memorably played by Tim Curry in the first film version of the book. You might have grown up with different representations of The Joker in Batman comics, or you’re extremely bothered by the clowns in government. Perhaps you know the true story of John Wayne Gacy? You can even find some Facebook pages for those who dislike these outlandish and oddly costumed creatures.

Rustic buffoon characters appeared in Classical Greek theatre and in the tradition of Commedia dell’arte. Shakespeare used Clown as a name for the fool characters in his plays ‘Othello’ and ‘Titus Andronicus’. So we may think of clowns as jolly and bumbling buffoons, manic and mischievous, but there has also been a dark side underneath the makeup and costume. The historian Andrew McConnell Stott, who wrote a biography of the pioneering whiteface clown Joseph Grimaldi, credits Charles Dickens with creating the idea of the scary clown. Grimaldi died a penniless, drunken, depressed alcoholic. He often quipped that he was ‘Grim-all-day’ so he could make people laugh at night. Dickens featured an inebriated clown in his 1836 serial ‘The Pickwick Papers’. A year later Dickens was asked to re-edit Grimaldi’s memoirs, which he then heavily re-wrote, emphasising the darker and more troubling aspects of his life that were masked by the humour. Stott explains it this way: ‘Without doubt, his most important decision was to place the biographical details of Grimaldi’s life within a strict economy of pleasure and pain that draws stark contrasts between the tinsel of the stage and the shabby reality of his many hardships. Laughter and misery becomes the balance-beam on which Grimaldi’s existence is constantly weighed as every career triumph is paid for with a proportionate personal agony, and every moment of joy countered by grief.’

The horror and grief that can be hidden behind the mask is picked up in a story by John Connolly from 2006. ‘Some Children Wander by Mistake’ tells of a ten year old boy fascinated by the circus, who uncovers a nasty secret about clowns, with their orange hair, white faces and prickly tongues. So beware, it’s a very short story to keep you awake at night. The last lines read: ‘They travel from town to town looking for those that they can steal away, always marking the child that kicks in the womb, and always finding him upon their return. For clowns are not made. Clowns are born.’

Today you will find a number of organisations using clowns for a social purpose. For example, Payasos Sin Fronteras (Clowns without Borders), founded in 1993 in Barcelona, aimed to improve the emotional situation of children suffering from the consequences of armed conflicts, wars or natural disasters. Back in the 1970s Dr. Patch Adams founded The Gesundheit! Institute in West Virginia, aiming to integrate a traditional hospital with alternative medicine. Part of this was the idea of ‘humanitarian clowning’, using laughter as an integral element of effective doctoral care, a concept emulated by many others. The Director of Public Health in Sandwell for 26 years, Dr. John Middleton, was a fan.

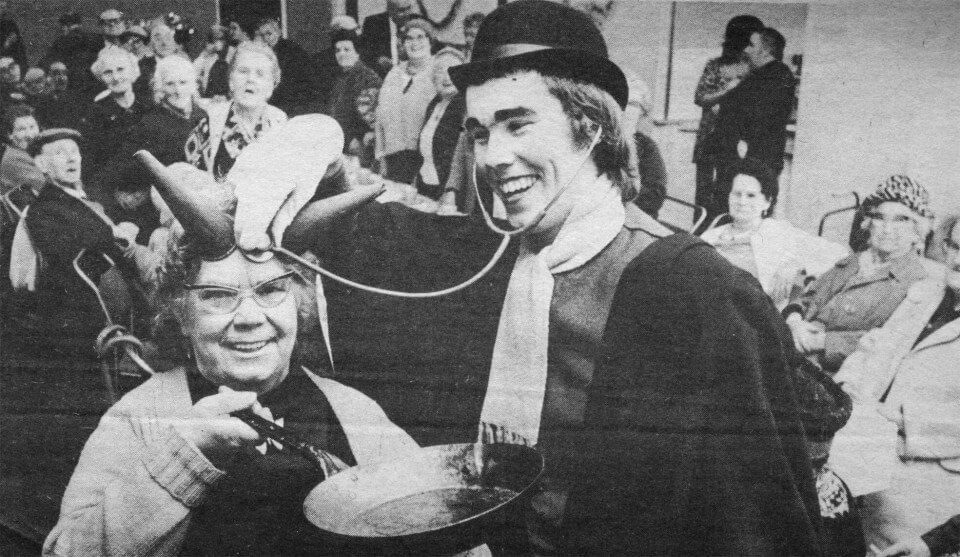

Here in the Black Country in the 1970s, Jubilee Arts had a monopoly of clowns. They were popular with local children and parents, rarely frightening, encouraging participation. Blotto the Clown accidentally broke things and local children helped repair them and protect them from thieves. The Compulsive Actor clown asked children to help him find lost thespians, as well as collect rubbish. Perhaps those were more innocent times, but we do wonder if the clowns were kept locked away after dark in a storeroom at the back of the Old Reading Room in Farley Park Lodge, banging their drums forlornly, having disagreements over punctuality, touching up the face paint, practicing their jokes on one another.

‘How do you stop a clown from laughing?’

‘Hit him in the face with an axe!’

‘What did the egg say to the clown?’

‘You crack me up!’

As Smokey Robinson put it: Now they’re some sad things known to man/ But ain’t too much sadder than/ The tears of a clown when there’s no one around.