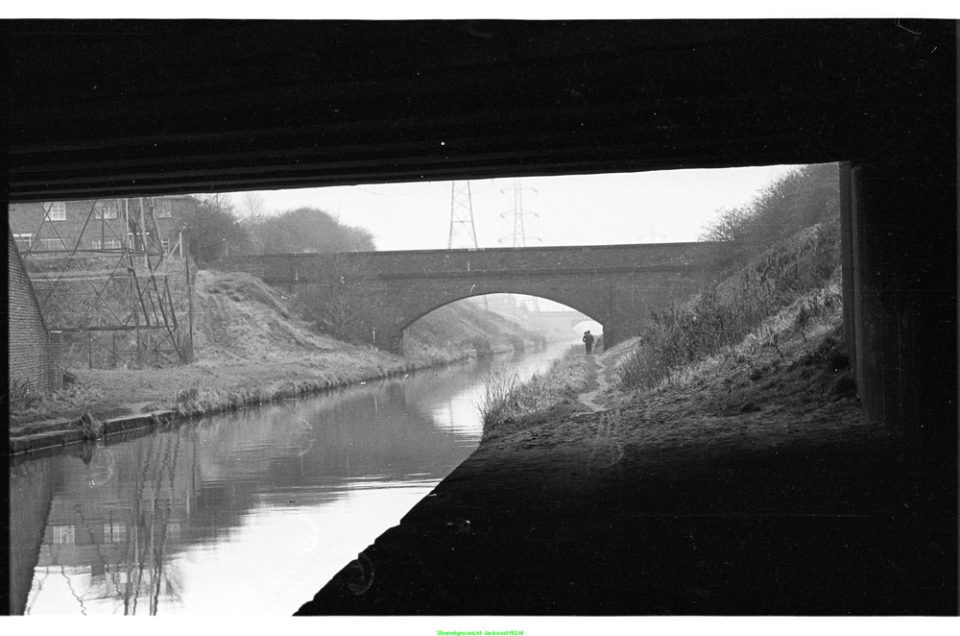

A patch of land, bounded on the southern side by the straight line of the old Tame canal, on the eastern side by Walsall Road, the river Tame itself, next to which is a sewage farm, and there runs the railway line with Bescot sidings on the northern side. On the western side, another branch of the river marks the boundary of the estate called Friar Park. Our Friar Park is not to be confused with the neo-Gothic mansion in Henley-on-Thames owned by Beatle George Harrison, with its caves, grottoes, underground passages, garden gnomes, and an Alpine rock garden with a scale model of the Matterhorn.

In the early 1980s, parts of the post-industrial Black Country could seem a depressing place at the best of times. This area had some of the greatest urban dereliction outside of the East End of London, a result of the decline of heavy manufacturing, especially metal foundries, and a legacy of the contaminated land. Even some 20 years later, one American critic wrote of the area: ‘There is nowhere in the world where it is possible to travel such long distances without seeing anything grateful to the eye. The Black Country looks like Ceaucescu’s Romania with fast food outlets.’

On a cold late February morning, the brightly painted Bus pulls onto the Friar Park estate, the leaden skies above making the place look bleaker than usual. They park up, set up the generator, get the kettle on, and wait for local youth to soon congregate.

The estate had been developed in the 1920s and 1930s to rehouse families from slum clearances in the centre of West Bromwich. Since the 1960s it stood in the shadow of elevated sections of the M6 motorway and was now a mix of semi-detached council housing, low-rise blocks of flats and some tower blocks, these later demolished in 2001. Unemployment rates locally were well above the national average, with youth unemployment aggravated with both low aspirations and poor skills and qualification levels. The process of deindustrialisation of the UK was well underway. Many local factories had closed – the year before, a British Steel Corporation subsidiary, Prothero of Wednesbury, sent 600 workers to the dole queue and nearby Patent Shaft Works had shut down, throwing 1,500 more out of work.

To persuade any of the Friar Park lads to cross the boundaries of the estate was like pulling teeth. Even when offered cash for the fare, they famously said: ‘Yow want us to catch a bus and go up West Brom. Yow’m ’avin’ us on, ai yer?’ You might say that this was a social hangover from the parochial nature of these Black Country towns; why go anywhere else when the factory, the school, the church, the corner shop or the doctor all were once within walking distance? To venture three miles down the road was a journey into a foreign land where queer folk abounded. While this reflected old entrenched views, it also revealed a lack of opportunity and aspiration.

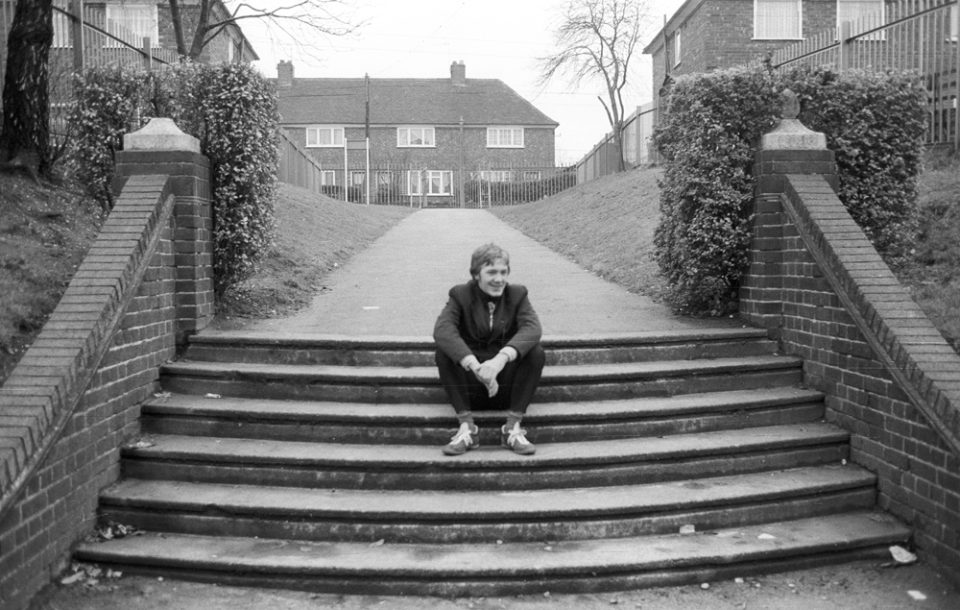

The arts workers from Jubilee had developed a relationship with the Youth Club attached to Manor High school. Opened in 1968, built on the site of a former smallpox hospital, exam results attained by school leavers were constantly low. Jubilee had also been involved in the Friar Park summer festival organised by local tenants. Together they planned to run some youth outreach sessions. Jubilee had just purchased a 35mm Pentax camera and the Bus now had a fully functioning darkroom for developing and printing photographs. This image comes from one of those first sessions.

The lads from Friar Park went onto to be involved in several art projects. They even got over their particular fear of leaving the confines of the estate, though they were torn between whether Wednesbury town centre or West Bromwich town centre offered a greater experience of the wider world.