The Government’s Microelectronics Education Programme ran from 1980 to 1986, exploring how computers could be used in schools in the UK. This photograph from Albright Secondary School, Popes Lane, Oldbury, shows a group working with one of the first micros, the RM 380Z. At that time the two most popular computers were these produced by Research Computers and Acorn – once touted as the British Apple, they built the BBC Micros. Whilst the two national broadcasters BBC and ITV were still producing day time educational slots for school lessons, these would soon no longer be needed with the advent of computers and video recorders. Great changes were afoot. This is the beginning of the future.

From Hansard Minutes, House of Commons, 25 January 1982

Mr Neville Trotter, MP for Tynemouth, asked the Secretary of State for Industry what progress has been made in the introduction of computers into schools.

Mr Kenneth Baker, the Minister for Industry and Information Technology replied: ‘Progress in my Department’s micros in schools scheme is excellent. A total of 2,300 applications had been processed by the end of 1981 and, with the extension of the scheme to all secondary schools from January this year, large numbers of applications are expected. I am very satisfied with the success of this scheme so far, and we are well on the way to reaching our objective of ensuring that every secondary school has at least one micro by the end of 1982.’

Mr Trotter congratulated his honourable Friend on the success of this imaginative scheme and asked if sufficient progress been made in the training of teachers in these schools to get the full benefit out of the machinery being installed?

Mr Baker replied that it was only his job to provide the cash for hardware, but he understood that it was the Department of Education were providing £9 million for the training of teachers and the provision of software. However, Mr John Garrett felt that the scheme was being undermined by cuts made by the Department of Education in training, but Mr Baker felt his colleague was exaggerating.

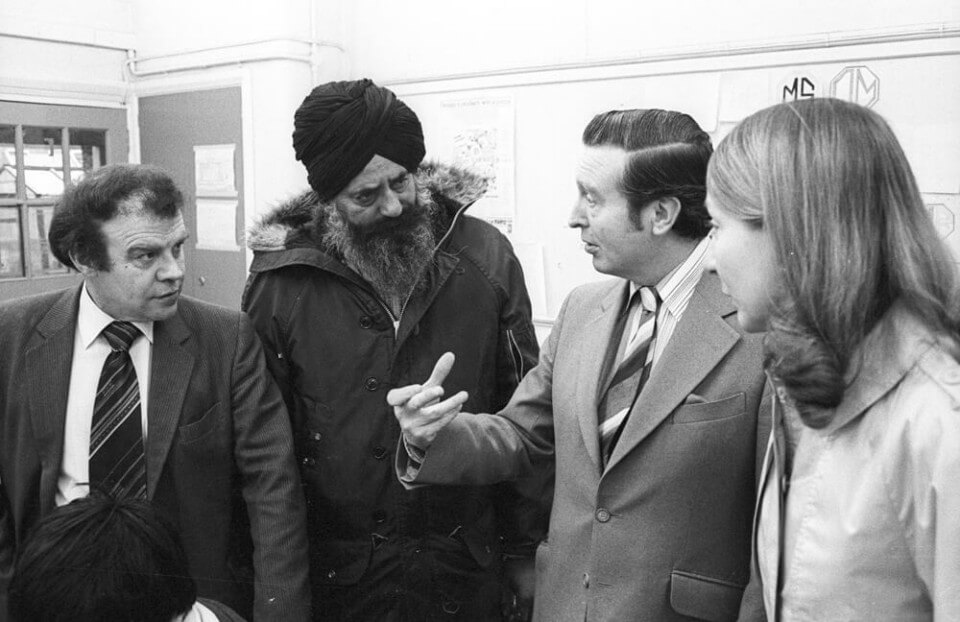

Albright was built in the 1930s, named originally Albright & Wilson after the adjacent chemical factory. By the 1980s, it was threatened with a merger with Oldbury High School and closure of their site. The school mobilised against this plan. On the day of this photograph, Peter Archer, the Member of Parliament for Warley West, visited Albright to hear the arguments put to him.

On a number of past occasions, as part of its outreach programme, the Jubilee Bus had visited Albright School – offering introductory photo and print workshops, those non-digital craft based activities. The Bus would park up nearby, at a lunchtime or just after school to demonstrate their wares. Recently, they had also worked with dinner ladies at Albright who were campaigning against cuts in services. As the education department proposed reorganisation, staff, governors, parents and pupils mounted a concerted campaign of opposition – using photographs from the Jubilee sessions as part of their argument, as well as the silk screening for posters. The campaign was ultimately fruitless, the school closed and became Sandwell’s Teachers Centre, though relationships developed with individuals were maintained and led to their involvement in other Jubilee projects.

Jubilee often found itself in conflict with the local authority in this way, and you might find it strange these days to think that one department of the council would help fund a local service which could be later found campaigning against another department’s policies. ‘Biting the hand that feeds you’, as they said. Yet this paradox was part and parcel of the structure of democracy, allowing for – even enabling – the voice of dissent.